There is the conflict in Ukraine, and then there is conflict over the conflict in Ukraine. Both the right and the left in the US are divided on the issue. How many resources should we send to Ukraine? How long should we maintain our commitment to the cause? Are we inching ourselves toward open military conflict with Russia and its arsenal of nuclear weapons? Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine is unjustifiable. The death and destruction it’s currently inflicting on Ukraine are atrocious. But does that mean that the US must intervene in the conflict, even at the risk of further escalation? I find that I have no easy answers to these questions.

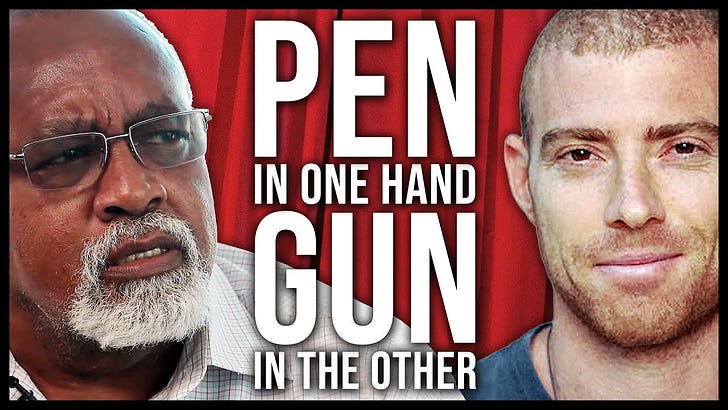

My guest this week, the writer Haim Shweky, does have answers, at least as far as his own commitments are concerned. He believes that Putin must be stopped, and he was willing to put his life on the line to further that end. Haim, an American-Israeli, served as a foreign volunteer alongside the Ukrainian army, and he’s come on the show to give us a first-person account of life at the front.

In this clip, he explains why and how he made the journey to Ukraine and why he thinks that Putin must be defeated. My own ambivalence about the conflict aside, I have to admire Haim’s willingness to live by his principles. One wouldn’t expect an aspiring member of the literati to strap on a rifle and charge out to face death. But as Haim points out, there are many examples of literary men doing exactly that. In fact, he wrote several accounts of his exploits for this newsletter—you can read them here. I’m relieved that Haim returned from Ukraine unscathed. Not all of his comrades were so lucky. We ought to bear that in mind as we contemplate our country’s own involvement in the war.

This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

GLENN LOURY: How did a young writer such as yourself end up on the field of conflict in Ukraine?

HAIM SHWEKY: I was living in the Mideast, in Israel and Palestine. I was residing there. I found myself a writer who really wasn't writing. My thoughts naturally turned to Ukraine. Sometimes the writer has to leap over his desk. One thinks of Byron in Greece or Orwell in Catalonia, Anthony Burgess in Malay, Hemingway in Cuba, Patrick Leigh Fermor, also in Greece. As a writer, I wanted to remove from between myself and the source a screen, a television screen. No matter how pixelated and sharp the screen, it'll never strike as vividly or impressively as it does the naked eye.

And as a writer, you want to remove as many veils between yourself and the subject as possible if you want to scrutinize it in a 20/20, severely analytical way. So I will not pretend to expertise that I don't possess, but I thought that instead of having the topographical view and study looking at the map, to be in that point on the map itself, trading ink for flesh.

I wanted to gain the perspective of the citizen and that of the soldier as well. From the bed to the barracks, from the home to the home base, from the capitals to the headquarters, from the cafes to the cafeteria mess hall. In that view, I joined the foreign legion. Most of these debates that go on—Ukraine, yay, nay—it seems to me most people are arguing from the gut rather than the pituitary gland.

I was hesitant they wouldn't accept me in an actionable capacity of joining the foreign legion, because there's a minimum amount of time that you have to go through basic training. Those who don't have military experience, most of them do not, as far as legionnaires. It's like an eclectic group, a hodgepodge of different characters. And they don't want to invest in you if you're only there for a brief spate. Through a lot of chutzpah and convincing, I got more than I asked for in the end. And I think in retrospect, I stood on those two objectives, given the time there.

You are an American by birth, but you're also an Israeli citizen?

American by birth and Israeli by birthright, put it that way.

Did your connections to either of your homelands factor into your judgment about the priority of serving and devoting your time in this way to the conflict in Ukraine?

In two ways. To get to Ukraine, you have to, perforce, go through the territory of Poland. There's no direct entering Ukraine. You go through Poland, and you basically show up at the border and you say, hey, I'm here to volunteer. Just like that. They guide you through the channels and check you and allocate you according to your potential and experience.

But the connection of Poland and Ukraine to Jews is a dark one. So in that sense, you don't hang a prince for the king's sins. And this experience I isolated in itself. I took this—what's going on, what Ukraine is undergoing—as an isolated experience. There could be a wrong yesterday and a right today. And whenever one hears rhetoric about certain people being a non-people, I think as someone who's been living in Israel and Palestine and with the history and the Jewish history of saying, “Well, you're not really ...” There's people to this day that don't consider Israel a real country, sort of a colonial outpost. Or, on the other side, the ultra-Zionistic contingent would not consider Palestinians a real people, but only a reaction against Jewish immigration.

And I think both these notions are very ominous and sinister, and we know where they lead. From the beginning, when you hear certain rhetoric, when you hear, for example, a megalomaniacal demagogue calling the people not a real people, I think the world ought to perk up to that. So in that sense, my history came to inform me. Perhaps I was a little more heedful of that message and the sinisterism that lurks behind it.

A writer has jumped over his desk. He finds himself bivouacked within shouting distance of enemy lines, buddies with whom he has developed very close personal friendships and allyship and so on. He's at war. The writer is at war. These sensibilities seem to—maybe I'm naive—clash with one another: the warrior, the martial, death.

No. How often do you read of the poet-warrior? King David. I think, the brain and the brawn. You have a pen in one hand and a gun in the other. I think these are complimenting each other. I think it's not necessarily that the pen is mightier than the sword. I think they both have their own points. But I guess it's right from the foot-marching of the soldier to the hand-marching of the penman.

But I do want to reiterate, and not belabor the point, that I was only there as a volunteer. I was only there for three months and my handful of missions is nothing compared to the paid career soldiers who are foreigners who went there, who are going to be there until the war ends.

Do you think some of your compatriots might have resented your transitory participation? That you had a certain date by which you were going to be out and they were going to be continuing on and subject to grave risk?

Well, I think that people are grateful for whoever comes through. Everybody has their contributions, and we'll all work together for this. It's not only on the field and in the barracks, but there are many people. When I was perambulating the still-free cities of Ukraine to when I was briefly in the foreign legion, I wanted to gain those two perspectives. And it forms one’s drive forward. So everybody's doing their part, as they say. I was honest from the beginning. I told them I had three months to give.

Glenn, did you have a chance to read this? https://harpers.org/archive/2023/06/why-are-we-in-ukraine/

It might be even more important for your guest to read it.

I think the US and Europe need to do what the authors of the article recommend.