We now stand at a pivotal moment in the history of race in this country. A new Supreme Court term begins tomorrow, and in the coming months, justices will decide about the future of racial preferences in affirmative action and will hear a redistricting case from Alabama that could severely undermine the reach of the Voting Rights Act. I think such a reconsideration is long overdue. These key legacies of the Civil Rights Movement—racial preferences and race-conscious redistricting—were, in my view, absolutely necessary at the time they were instituted, but they have in some respects outlived their usefulness and may now do more harm than good. It is time—past time—to move forward.

But just because we’re moving forward does not mean we can forget about the past. There is no better time than now to think back with a critical eye on the conditions that brought about landmark mid-century civil rights legislation and Supreme Court decisions. Below I do just that in a long interview from 2019 led by Bucknell University sociologist Alexander Riley, which is taken from his edited collection, Reflecting on the 1960s at 50: A Concise Account on How the 1960s Changed America, for Better and for Worse. In it, I speak at length on Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Black Panthers, affirmative action, mass incarceration, and reparations, among other topics.

We cannot know what the consequences of the coming Supreme Court will be until its decisions play out in the real world. Likely there will be growing pains, bumps in the road, and struggles at the state and federal level. But I do know that, while we must never forget from whence we've come, we can no longer afford to live in the past

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

ALEXANDER RILEY: A certain narrative, defensible if not definitive, of social activism on the issue of race in the ‘60s goes roughly thus: Up through the mid-‘60s, the movement was dominated by individuals and groups that framed the need for change in traditional American cultural and political terms, invoking both the American constitutional republican tradition and Protestant Christianity in the philosophical argument for racial justice. Later, movements and individuals that embraced more radical, even revolutionary philosophies became more prominent. Some argue that, of late, the latter have contributed more than the former to the dominant spirit of racial activism in the country, both in the universities and in the larger public sphere.

What are your thoughts on this? As someone who has more than once described yourself as someone inspired by the words and deeds of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., do you think King’s spirit is still alive in the racial justice movements of 2019, or has he been replaced by the spirit of the Black Panthers, the later SNCC, and BLM?

GLENN LOURY: The framing of that question is not a neutral move. I’m going to answer the question in due course. But I want first to respond to the framing of the question. It creates an opposition between a belief in the American system and a magnificent promissory note unfulfilled, the vision of the Founders about ideas of freedom, Abraham Lincoln‘s reinterpretation of the Founding to include the descendants of slaves versus angry black people in the streets, Malcolm X’s bellicose language, the Black Panther Party’s militancy, Black Power.

You’re asking me, as it were, to choose or parse that opposition. That’s not a neutral framing. I’m not trying to be difficult. But the separatist strain, the radicalism and rejection of the American project as it applies to the Negro, predates the 1960s by quite a ways, as I’m sure you know. Malcolm X is out of the Nation of Islam. I grew up in Chicago in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The Nation of Islam was then already well established. We can go back a few score years to the debates between the followers of W.E.B. Dubois, on the one hand, and Booker T. Washington, on the other, and you can see that same kind of tension.

I’m not a historian, but I can imagine some historians of the period also saying that King’s effectiveness and his kind of accommodation, his pose, and his kind of credulity, and acceptance of the American national narrative as the framework within which he was going to elaborate his own aspiration, his effectiveness in that regard, was dependent to some degree upon the tacit threat that the radicals and the possibility of radicalism posed. We can’t really set these two things on one side versus the other. We have to think about them in some kind of symbiotic way.

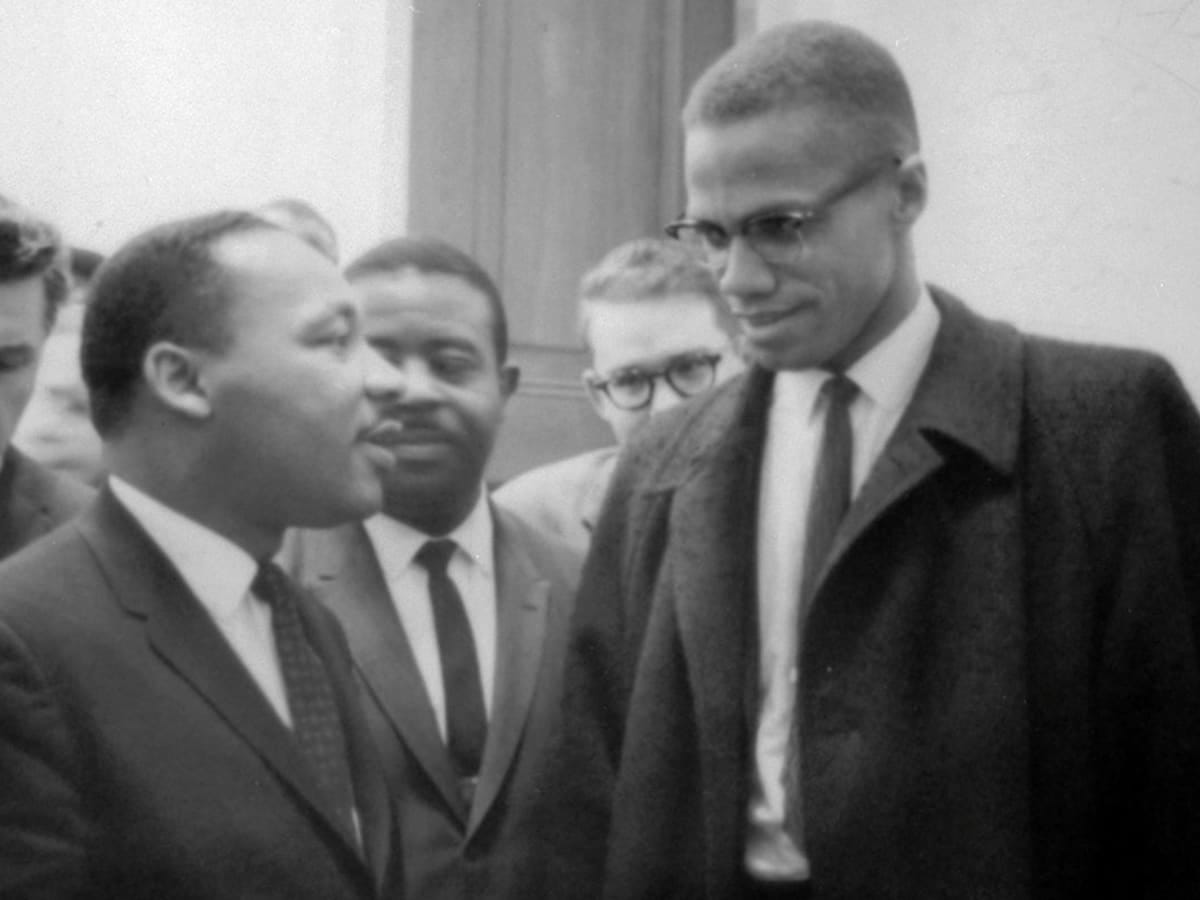

But let me respond then in more in the spirit question rather than as a critic of the framing of the question. I would take what the King-Southern Christian leadership conference / A. Philip Randolph / Bayard Rustin / National Urban League / NAACP moderates accomplished, in spearheading a movement that actually ended up with very far reaching legislative enactment that transformed the landscape governing African American life, opened up opportunities, brought the country around to a different way of looking at its obligations to the descendants of slaves, and put a nail in the coffin of Jim Crow. And this happens within my lifetime. I’m born in 1948.

I would hold that up to contrast with what the radicalism, what the shouting of “Black Power,” what the rioting in the cities, what the Black Panther party accomplished, and I don’t think it’s close. I think that the fruit of King’s moderation dwarfs that of the radicals in its continuing impact on the lives of all Americans including African Americans. I’m not pooh-poohing radicalism as such, but I’m saying at the end of the day, in a democracy, when you’re a small fraction of the population and you’re seeking to change the structures, you ultimately have to persuade your fellows. How do you persuade them without at least to some degree embracing the values, the norms, and the national aspiration that animate your fellows? You can’t stand outside the system, threatening to tear it down at a moment’s notice, evidencing contempt for the things that its people hold dear, declaring yourself preemptively as not a part of this enterprise, and expect that you’re going to move the needle on how it is that the enterprise conduct its business.

At a pragmatic level, I would give the nod to the moderation of Martin Luther King Jr. People say, and they say it today every time the national holiday comes around that honors King’s work, they say: “I’m tired of hearing about that 1963 ‘I have a dream’ speech. I’m tired of hearing about it. That was early King. The King that we ought to be focusing on is the one who stood up in Riverside Church in 1967 and denounced the Vietnam War. The King we ought to be focused on is the one who was leading a poor people's campaign at the end of his life. The one who was at a garbage workers strike in Memphis when he was assassinated.” That’s what they say. “Don’t give me no warmed over, toned down, pablum King. Give me the King that was rocking the boat, and that had seen the problems with capitalism, that had seen the problems with American imperialism and racism and was prepared to call them out.”

I get why people are saying that. I get why contemporary social justice activists are impatient with the color-blind “I have a dream that one day my children will be judged by the content of their character. Black and white will walk hand-in-hand together, etc., etc.” I understand people's impatience with that rhetoric in our current day, but I just ask people to reflect on what the power of that rhetoric actually was in transforming structures in American society. Again, I don’t think the threats of violence, the rejection across the board of American norms, the contempt for patriotism, the classification of the Founding Fathers as a bunch of dead white males, half of whom were slave owners anyways, and “we were 3/5 of a man in the constitution,” I don’t think that kind of rhetoric gets us anywhere. So there’s that.

You also mention the fact that King is a Christian minister. He’s a Protestant minister. And the lifeblood of that movement to a certain degree, and certainly its institutional grounding, is flowing through the African American church. He’s speaking to a largely Christian and religious nation, asking people to take a good look at what the meaning of the creed might actually be. Their civic creed, but also their religious creed. Speaking to them with the authority of the Christian ministry, the African American religious heritage out of which he comes. The anthem of the movement, the role that the church plays in that, and I look with positive attitude on that aspect of that movement. Of course, we are—with the First Amendment and everything else—a secular and not a religious civil order, but as a matter of culture and social structure, religious faith played a very important role in that movement.

I hope I’m being responsive to the question. Don’t ask me to choose between the expressed anger and rage of a people who have had a boot on their neck, on the one hand, and who have given a voice to their frustration and to their fury through being tempted, and more than tempted into a radical vein, between that, on the one hand, and the effective public ministry of a Christian leader who begins with the premise that the state is legitimate, that on the whole the enterprise is reformable, that those whom he is petitioning can hear his plea, that in fact the nation is worthy of the allegiance of African-Americans if it only would live up to its creed. Don’t ask me to choose between those two. I have asserted what I think is the relative historical significance of those two registers of African American political expression, but I do think I can understand how it is that both would have come to be.

I’m thinking about my Uncle Mooney right now. I grew up in Chicago in the 1950s and ‘60s, as I said, and Uncle Mooney, my mother‘s sister‘s husband, was a small-time businessman, a barber, a dry cleaner. He struggled all of his life. He would bring to our home, the home I grew up in, the Muhammad Speaks newspaper of the Nation of Islam. He’d bring a copy home every week and leave it on the dining room table. He’d thumb through it. He wasn’t a follower of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, but he did admire the defiant, independent streak of “I’m not waiting for the white man.” He used to say: “You all talking about King and company, talking about integration? I’ll tell you what, you call me when they start integrating the money!” That's Uncle Mooney. “Call me when they start integrating the money.” He was an atheist. He thought that these preachers going around with their mealy-mouth spirituals begging white people to relent was undignified. “Unmanly,” he would have said. I get that, I really do get it.

But at the end of the day: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the transformation of the sensibility of much of the American republic such that the social conventions of the Jim Crow South ended up becoming absolutely unacceptable to the mainstream sentiment of the country. You can look at the attitude surveys, and you can see all this change in people’s willingness to countenance interracial marriage, in their belief that blacks were entitled to be able to petition for equal citizenship, and so forth. There’s a reason why there’s a Martin Luther King Day and there’s not a Malcolm X Day. I’m talking about the civic culture of the United States. There’s a reason why there’s a monument on the mall to honor the work of Martin Luther King. There’s a reason why the Nobel Peace Prize Committee decided to anoint him so. And that’s not nothing. That’s quite a bit.

I’m almost inclined to push a little further on that. Just to confirm, your point is well taken, that both of those halves of the Civil Rights Movement played off one another to a certain degree, even though they were antagonistic too in lots of ways, but there was that symbiosis. But aren’t you choosing without choosing, at least if the criterion is effectiveness, or efficacy? Or am I misinterpreting you?

No, no, you’re not misinterpreting me. And I think that the memory of that period, at least as it animates activism on behalf of African Americans today, probably gives less respect than it should to King, and it lionizes to a degree that I might regard as excessive the Black Panther Party which was a lot of different kinds of things going on all at the same time. It wasn’t just free breakfasts for kids and a defiant stance against belligerent police, it was a lot of things going on. You just take a look at what happened in the lives of the leaders of the Black Panther Party as we go some decades forward, and it’s not entirely a pretty picture at all.

I think there’s this kind of romanticism in a recollection about resistance and radical uprisings, Watts 1965, Detroit 1967, and many others. There’s a, “Yeah, that was really Black Power asserting itself, that was black people asserting themselves!” and a contempt or disrespect for—in the spirit of Uncle Mooney—the more accommodationist and compromising moderation and Christian faith of the movement that King was leading. Our present day social justice advocacy on behalf of African Americans might benefit from a rebalancing in which you push down a little bit the weight on the radicalism and push up a little bit the weight on the moderate side. In other words, I need to persuade the rest of my fellow Americans who happen not to be black, not by berating them for being racist and threatening to burn down the house, but rather to buy a credible argument on behalf of broad social policies in the interest of working people across the board.

Let’s talk about two substantive topics that you’ve written a good deal about over the years. The first is affirmative action, and the second is criminal justice. What is your perspective on the track record of affirmative action as a set of policies geared towards trying to address racial inequality? How optimistic or pessimistic are you about the likelihood that affirmative action policies can have a substantial impact on alleviating questions and problems of racial inequality?

There are different kinds of arguments about affirmative action. One of them is a legal argument about whether or not the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees equal protection of the laws to all citizens, is consistent with the practice of using the racial identity of individuals as a factor in treating them in terms of the allocation of resources and opportunities, admissions to colleges, employment, government contracts, and so on. Is it ipso facto unconstitutional to use race in public decision-making that benefits blacks and Latinos and women and so on? That’s one kind of question about affirmative action.

Another kind of question about affirmative action is this: Bracketing for a moment the constitutional issue and assuming for a moment that there isn’t any sort of trump card, there isn’t any killer argument that negates affirmative action a priori, is affirmative action leading to outcomes that would lead us to question whether it is wise social policy? I want to discuss affirmative action in that manner. I am very much influenced by a book by the legal scholar Randall Kennedy at Harvard. The book is titled For Discrimination. What Randy argues in that book is, yes, affirmative action is racial discrimination. Now it might be strange to think that’s something that has to be argued for, but a lot of people deny that racial discrimination is going on. It’s not racial discrimination, they say, if we’re using a policy in order to try to rectify the effects of past racial discrimination.

But I think Randy is right to observe that if a university is using the race of applicants as part of how it’s making its decisions, if a government agency is using the race of potential vendors as part of how it determines whether or not to let a contract, if an employer is using the race of applicants as part of a calculation about whether or not to offer a job, then to the extent that they are making use of race as a factor in that decision-making they are engaging in racial discrimination. Professor Kennedy says it’s racial discrimination, but he says it’s not racial discrimination that’s inconsistent with the 14th Amendment. How perverse would it be to interpret that Amendment, enacted with the expressed intent [of] ensuring the equal citizenship of African-Americans, how perverse would [it] be to interpret it as enjoining a state actor from what would otherwise be thought of as reasonable and moderate use of race, with the purpose of trying to reverse the consequences of historic racial discrimination?

That would be perverse, says Kennedy, and I tend to agree with that. I’m not one of those who would respond to affirmative action by saying it’s discrimination against non-black or non-Latino people and therefore it’s wrong and must not be done. It is discrimination to the extent that it’s undertaken to benefit blacks or Latinos, but it’s not discrimination that I think should be prevented on a constitutional argument. That’s one thing that I would say.

But we are here in the year 2019. Affirmative action is something that dates back to the late 1960s, and really gets going in the 1970s. President Lyndon Johnson famously says, I believe it’s at a commencement address at Howard University in 1965, that you don’t take someone who’s been hobbled by history, the chains that encumber them, and remove the chains and bring them up to the starting line of a race and then you set the race off and expect that you’re being entirely fair. This is a paraphrase of Johnson. What he says is we need equality as a fact, and equality as an outcome, not merely equality in principle or equality as a theory.

We are a half-century into this idea that we’ve got to do something special for the blacks in the competitive venues where they lag behind in order to ensure equality of opportunity. A half-century, that’s a long time. It's as long from Johnson giving that speech in 1965 to where we sit right here, today, in 2019, as was the time that expired between Appomattox, where Lee surrenders to Grant, and Versailles, where the First World War is brought to a conclusion. That’s a long time. That’s three generations. It's a long, long time.

What I’ve been saying about affirmative action of late is that I don’t want to argue about whether or not it’s appropriate or just or whatever. I just want to get you to think about the fact that we are now well along the way to institutionalizing, as a permanent manner of how we do business, how we admit people to elite colleges, how we decide who’s going to be on the faculty of a university, how we decide to think about the allocation of business opportunities when the state goes out and spends billions of dollars building highways or purchasing materials, we are now well along the way to institutionalizing as a premier practice, using a special set of considerations when evaluating African American aspirants, and putting your thumb on the scale on their behalf.

Now here’s what I want to say about that. It’s not equality. It certainly is a distribution of benefits in the direction of African Americans. That it is. It’s a benefit to some African Americans to be able to enjoy opportunities that they wouldn’t otherwise enjoy because of affirmative action. But if the goal is racial equality, baking into the cake the practice of treating blacks specially in virtue of their blackness, people who were born in the year 2005, is not equality.

I am a college professor, and we are on a college campus. The question of affirmative action in higher education is a natural one to contemplate. I’m not sure what goes on [at Bucknell], but at Brown we get over 35,000 applications a year, and we admit about 1,800 people. That’s a pretty selective operation that we are engaged in. We are an elite institution. Average SAT score, I’m sure it’s over 1400, combined math and verbal. It’s an elite enterprise. Do we really want to build into our policy going forward, forever, the idea that blacks simply can’t be judged to the same standard with respect to this kind of undertaking?

If indeed it’s the case that African American applicants to a place like Brown University are on the whole not competitive—the numbers would be 3% or 4% instead of 12% or 13%, if you did not take race into account when you made the decision about whom to admit—if indeed that’s the case, do you think that you are going to get to equality by institutionalizing the practice of lowering the bar? “Oh, she’s black. She’s got an 1150, but that’s okay. She’s black.” Do you really think that’s going to get you to equality? It is not! As a remedial enterprise, undertaken in a transitional way, with the intent of directly addressing historical inequity, and trying to get on a different track than what had been the case in 1975, okay, I can see that. As a permanent practice, as the way of doing business, as the, in effect, compensatory endowment to people of color so that they can be represented in numbers that don't actually reveal the disparity in their performances? It's a lot of things, but it's not equality.

It leads to a lot of things that are not healthy, like patronization. The soft bigotry of low expectations. “Oh, we don’t really expect our African-American students, who are presumptively disadvantaged ...” Think about that! You’re black and you’re presumptively disadvantaged? By virtue of being black? “We need diversity, we need representation!” Oh, I see. Now the African Americans who are included in this rat race competition to get into these places—everyone here knows what I’m talking about, you apply to 20 colleges because you don’t know whether you’re going to get into one of them or not—we create a world in which the presence of those African Americans is justified because they leaven the mix? Because they bring some color to the table? It’s a lot of things, but it’s not equality.

What I’ve been saying of late about this question is this: Okay, you want to do affirmative action? Go ahead, go ahead. I’m not going to fall on my sword about it. I’m not going to throw a fit. No, no, it’s not the same thing as racial discrimination against blacks in history. You go ahead and do it if you want to do it, but if you really wanted equality, you wouldn’t be satisfied with that. If you really wanted equality, you would address yourself to the foundational root of why it is that African Americans as a population are underrepresented at the right tail of the distribution of intellectual and academic performance. Unless you do that, unless you change that foundational root, you will never get equality.

You decide. Do you want representation or do you want equality? Do you want titular representation, do you want a cover story, or do you want equality? Are you interested in developing the human potential of the African American population? Or are you merely interested in covering your ass? By being able to present an optics that shows that you’re a diverse and inclusive institution?

No, I’m not against affirmative action. But I’m against hypocrisy. I’m against condescension. And I’m asking people to imagine what kind of country we are going to be. Really? We are going to do this for another 30 years? We are going to do this for another 50 years? This is where we are going to be? In my mind, it’s an unacceptable vision for our country. That we are going to depend upon treating black people differently because everybody knows they can’t cut it. Unacceptable.

There was recently this controversy about the exam schools in New York City: Brooklyn Tech, Bronx Science, Stuyvesant. They have an exam. They give the exam. Tens of thousands of people take it. They are admitting only hundreds. Stuyvesant constitutes a class—an incoming class for the fall next year—of 895 admits. Seven of them are black. And the newspaper article says, in the spirit of affirmative action, “Racial Segregation Returns to New York City’s High Schools.” The presumption is the low number of African Americans being admitted is a reflection of the failure of the institution to be fair and open to all people.

It is not! It’s a reflection of something else, something less pretty, something much more challenging, something that goes much more profoundly to the heart of what's wrong in our country. It’s a reflection of the failure to develop the human potential of those youngsters who happen to be black. The test is only a messenger. It’s merely telling us what people know and what they don’t know. Some respond, “Well, let’s get rid of the test, let’s put a quota on the schools, let’s raise those numbers.” But why not, “Let’s develop those people so that they can compete”?

I saw some statistics the other day about Brooklyn Tech where over 60% of the students are Asian, and that more than half of them are also disadvantaged, in the sense that they qualify for public benefits. They are not rich middle-class kids on the whole who are floating into Brooklyn Tech because their parents bought a test prep book for them. They are youngsters, many of whom are disadvantaged, who are developing their capacity to function in the high-tech world that we live in the twenty-first century. The low number of African Americans who are exhibiting that degree of excellence is a warning sign. Not about whether or not Brooklyn Tech or the New York public schools are racist, but whether or not our society is developing the human potential of all of its people.

Now we can go into the reasons why, and they will be many, and the fault will not fall only on white people. We can talk about why our youngsters are not performing better. Yes, they deserve to have better schools, and maybe they deserve to have different parenting, and maybe the culture is to some degree to be faulted. And I know I’m not supposed to say that, but what I can see is huge differences across racial groups in their ability to function within American society, and what I can tell you is nobody is coming to save our black youngsters from the loss of developing their human potential. Nobody is coming.

My views about affirmative action have evolved, obviously, over time. I used to be one of those people who said, “Oh no, it is just racial discrimination, it is just reverse discrimination, and we shouldn’t do it.” And then I became one of those people who said, “Oh no, wait a minute, I do think we need to defend affirmative action.” And now I am one of these people who is saying, “Are we ever going to get serious about the actual problem of inequality and address ourselves to it? Affirmative action doesn’t take us to that point.” Imagine how weak, and, at the end of the day, pathetic it is to be in this position of begging not to have affirmative action taken away. Throwing a tantrum not to have them take away affirmative action. “We want our affirmative action!” Pathetic!

The world’s becoming a small place. There are billions of people on the planet. The Internet is bringing everybody online, and it's bringing everybody into the mix. We need to develop our people’s potential. No, I don’t think that we can do that alone, but I don’t think affirmative action is very helpful in addressing the problem.

What are some of the other things that American society ought to be doing to enhance the human capital of these kids?

Anything that we might be doing, and we can talk about education, we can talk about poverty and we can talk about opportunity and we can talk about the way cities are organized and concentrated poverty in the cities and what not, but anything that we would be thinking about doing, if it’s charter schools, if it’s more money, if it’s investing in early childhood education, if it’s higher quality childcare, whatever we might be talking about, we can’t talk about that in the nation of 330 million people here in the United States of America strictly in terms of racial equity.

These are matters that have to do with the development of all of our people, including African Americans. I don’t regard the public government policy discussion about what do we do to address the achievement gap as something that should be discussed primarily in racial terms. I think that part of the conversation—African American underachievement—has got to be a conversation that happens amongst African Americans about our own institutions and our own communal values and our own social practices. It’s hard not to notice that the structure of African American family has undergone dramatic changes in the last half century. The effect on the child development of the parenting practices and so forth is something that needs to be taken seriously. Peer influences are a factor. The longer I talk, the more trouble I’m going to get into, because I’m not actually presenting any solutions. It’s just going to look like I’m waving a finger of indictment at people, which I may be doing to some degree.

Let’s move to the second of the two topics I introduced earlier. You’ve had a lot to say about the criminal justice system and how it intersects with race relations and racial inequality. What are your thoughts, especially in light of some of the things that have been proposed recently in the Trump administration as reforms of the existing system, about what direction we should be going in if we want to address what many argue are basic problems of racial inequity in the administration of criminal justice in the country?

Criminal justice, criminal justice reform, mass incarceration, Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow, Glenn Loury, Race, Incarceration and American Values, the racist character of the American criminal justice system, William Jefferson Clinton signing into law the 1994 omnibus crime bill, etc. War on black people.

I gave these lectures at Stanford—it’s been over a decade now—that were published as a small book called Race, Incarceration and American Values. And I was very angry when I delivered the lectures. I was outraged at the fact that we had, as a nation, chosen as the primary instrument of our response to the problems of underdevelopment of African American potential and social disorder in our urban environments, we had decided that the primary instrument that we would use to address ourselves to the social disorder and the problems that emerged was going to be punitive. We were going to lock them up and throw away the key. We elaborated a politics in which people would run for office basically on that kind of finger-pointing and the promise that they were going to be tough on crime.

We had constructed these institutions of prisons that had grown from 400,000-450,000 people under lock and key on a given day in 1980 to two million under lock and key by the time we get to the year 2000. A massive footprint—the so-called prison industrial complex—an institutional mechanism for controlling people, for physically confining them. I thought it an outrage that our moral sensibility didn’t look beyond the immediate problem. We have an offense, we need to punish the offender, we need to protect the people that have not yet been victimized, and stand up for those who have been victimized. We need to choose between the innocent prey on the one hand, and what we are going to do with these thugs on the other. That kind of sensibility, I thought it and still think it outrageous. It’s wrong.

Looking around the world, American society is a vast outlier compared to other comparable democratic industrial societies in the extent to which we relied on incarceration. The war on drugs, balancing our cultural budget on the backs of the weakest of our fellow citizens. What an outrage! We don’t want our kids to use drugs. There is a market. It's a $100 billion a year market in heroin and methamphetamines and cocaine and marijuana, and so on. It’s a huge, huge underground economy.

Who do you think is going to be a foot soldier in such an enterprise? Somebody with a bright shiny future because they’ve got a college degree or they’ve got middle-class parents? Or somebody who grew up in a housing project running with gang members and so forth, who flunked out of high school and hasn’t got any hope, any prospects? The latter. The latter are going to be the people who you are going to find on the street corners, darting over to the car as the suburban buyer drives by with the window down, $100 bill going out the window, couple of small packets of cocaine coming in.

Who do you think is going to be the one who's risking his life with $3000 in his back pocket and a pistol tucked into his belt, because he doesn’t want to get robbed? Who do you think is going to do that? Of course, it is going to be people who don’t have any other prospects. Of course, black and Latino youngsters are going to be overrepresented amongst those, and so you don’t want your kid to use drugs? You think drugs is a scourge on the society? And you elaborate a law enforcement and punishment regime that basically puts the weight of that on the weakest and the most marginal of our fellow citizens, when it was a social problem to begin with. That’s horrible, in my mind.

Of course, the war on drugs is not the only thing going on about incarceration. Certainly today—I don’t know about 1980, but we can look, and I doubt that it was true then either—the vast majority of people incarcerated were not incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses. They were incarcerated for violent offenses and for property offenses. But, even so. “Mass incarceration is racist, America is a racist country because of mass incarceration, mass incarceration is the new Jim Crow.” That narrative had and has a lot of appeal to me.

On the other hand, I think about what it would mean to be insecure in my property and person as an ongoing condition of my life, living someplace that I can’t afford to move away from, where crime rates are high, and where people are being preyed upon. I think about when people talk about abolition of prisons, and they are serious about it, and they’re using race and racial inequality as part of the advocacy, the justification for their advocacy of that. I think about the people who have to live with the consequences of violent criminal acts taking place in their midst. I think about the grandmother who has to bury the six-year-old child that's shot in the head by a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting between two belligerents. I think about the person trying to get gas at a pump at two o’clock in the morning and someone comes along to jack their car and when they don’t hand their keys over right away, they end up with a slug in the chest.

And I think maybe our sentences are too long. Maybe what we do when we confine people has no aspect of human development to it and is only about punitive confinement and we could do a lot better. Maybe we can learn something from the Germans or the Swedes about what you do with people whom you are removing from society, at least temporarily, that gives them some prospect of having a different life when they return. Maybe we needn’t have this kind of collateral sanction regime where we disqualify a person from eligibility for Pell Grants or public housing or whatever it might be because they’ve offended. They’ve made a mistake, they’ve paid their dues, and they want now to come back into society, but we nevertheless hang this thing on their necks because we are still mad at them for having violated our social compact. There is a lot of room for reform, it seems to me.

I think capital punishment is an abomination. I don’t know why it is that the state needs to take human life in ritualized ceremonies of revenge, extirpating human life. There’s no necessity in that. There is a racial disparity, and though the number of people being executed is a relatively small number, there’s still the symbolic aspect of it. It should not be acceptable practice in American politics to do what George Herbert Walker Bush did to Michael Dukakis in the 1988 election, where Dukakis endorsed a furlough program for prisoners in Massachusetts, and one of those prisoners, Willie Horton, who happened to be black, ended up committing a horrible crime while out on furlough. Lee Atwater and George Bush hung that around the candidate Dukakis’s neck, with a commercial that showed a black man going through a revolving prison door, and you can imagine what that would trigger in the minds of a person who is listening to it about what that person might do.

On the one hand, I am on the record as objecting to the elaboration of this massive punitive set of structures that we have elaborated, and I think it does need to be pared back. Frankly, I think that if the bulk of the people suffering from it had been a little bit more sympathetic to the median voter in a lot of jurisdictions, that is to say, if they’d been white, you would have seen some questions being raised. Stop and frisk? Three strikes and you’re out? Three felonies and you’re going to jail for 25 years to life? You would have seen a different kind of management of this problem. I think that. I think we don’t do enough to try to put people in position when they can be constructive members of society, given that we do have their attention while we are confining them, and so on.

On the other hand, I think about the fact that the people who have mostly to deal with the depredations of criminal offending are themselves members of racial minority groups and low income people. They can’t move away. They can’t hire a security guard. They can’t build a wall around themselves to protect themselves from the threats that lurk outside. I take a more nuanced view about this. I’m not one who is going to sign on to the abolitionist movement with respect to prisons. I’m not one who thinks that the fact that there are institutions of law enforcement and punishment is in and of itself an act of racial domination. I do want to hold people responsible for the acts that they undertake. I want to give them the benefit of presuming them capable of making choices other than the ones that they’ve made. I don’t want to say about them “Oh they are poor, they are black, they grew up in a ghetto, and therefore what could we expect?” That seems to me to be terribly patronizing.

What do you think about the fact that reparations talk seems to have returned to American politics of late, with some of the Democrats running for their party’s nomination for the presidential election taking strong public stances for reparations?

I remember the book by Randall Robinson that was published, I think, in 1999 or 2000. The book was called The Debt, and it was a passionate argument for the case that African Americans were due reparations. And of course I recall Ta-Nehisi Coates’s influential, long essay in The Atlantic, only a few years ago, “The Case For Reparations.”

I don’t think it’s a good idea. Are African Americans owed reparations? There are a number of lower-level, technical issues, like who’s an African American, for the purposes of that question, given that the population is composed of people who have come from various places at different times and so forth. There are philosophical questions about whether or not the intergenerational obligation incurred by the fact of chattel slavery, or the denial of equal citizenship to the immediate descendants of the slaves, creates an entitlement or a benefit that is appropriately endowed on or to a contemporary people who happen to be African American.

I actually think that little bit of the question is kind of interesting, and maybe even ironic to me, because if I said that the family has a right to pass his wealth on to from one generation to the next without the encumbrance of inheritance tax, or call it the death tax as Republicans like to call it, a lot of progressives would say “Oh no, oh no. Just because your father made a lot of money doesn’t mean you’re entitled to anything. You didn’t earn it.” Well, likewise, just because my ancestors may have been deprived of the fruits of their labor by being forcibly enslaved doesn’t mean that necessarily that I am entitled to anything. I really don’t see, conceptually, a distinction between one or the other. In some sense, intergenerational entitlement being transferred from one generation to the next is intergenerational entitlement being transferred from one generation to the next.

But that’s not my main point. Do the facts of slavery, and Jim Crow segregation, and inequality, and restrictive covenants, and racial discrimination, and poll taxes, and literally tests, and anti-miscegenation laws, and all of that figure in a social scientifically identifiable way in accounting for some of the disadvantage of African American? I have no doubt that that’s true. I have no doubt that history casts a long shadow, that some dimension of African American poverty does indeed derive from historical mistreatment of African-Americans. Saying how much would, it seems to me, be a bridge too far. I don’t know how you do that as an empirical project.

But the qualitative claim that history casts a long shadow and is implicated in the condition of African Americans it seems to me is certainly true. But I don’t go from that observation, as Ta-Nehisi Coates does in his essay, as Randall Robinson does in his book, from the observation that history casts a long shadow and that the dispossession of my ancestors has to some degree affected my opportunity to the conclusion that a contemporary program of the government getting in the business of distributing reparations to African Americans is a good idea. In fact, I think exactly the opposite. I think the fact that history casts a long shadow has an implication, which is that the determination to redress the consequences of that history is open ended. It is not quantifiable, it is not commodifiable. You can’t convert it into a commodity and trade it on a table as a quid pro quo.

What I fear about reparations advocacy is its success. There are 30-odd million African Americans, maybe it’s close to 40 by now. What’s the number going to be? $10,000 a head? Let’s see, $10,000 times 40 million is $400 billion. Maybe it’s $100,000 a head. That’ll be $4 trillion. And then what do we got? We got some people with money in the bank. Certainly they are better off. And we also have a nation that can do like this [wipes hands together] with respect to its obligation to reckon with the consequences of whatever its historical mistreatment of black people has wrought. Commodifying the claims that African Americans have on the nation discharges the obligation.

Do I really think that the Congress of the United States, or anybody else, is going to enact payment adequate in their magnitude to indemnify the recipients from the possibility that they might yet find themselves again in a position of disadvantage? I don’t think so. Do I think it’s going to make reading scores go up? I don’t think so. Do I think it’s going to make incarceration rates go down? Maybe only moderately. Do I think it’s going to lead to a rectification of all the problems that we have and all of the gaps that we have and the disparities and a disadvantage? Actually, I don’t think so.

My problem with reparations is that it converts what ought to be a relational discourse—how do we relate to our fellow citizens and what are our obligations as Americans?—into a transactional discourse: “I am getting paid? You owe me.” It puts what ought to be all of us together confronting the problems of disadvantaged people in this society into competing groups on either side of a bargaining table. I can’t believe that the Democratic Party is going to go into this election against Donald Trump with reparations as one of the arrows in their quiver.

I get why a Democratic primary candidate who wants to win the South Carolina primary would do that because he’s pandering to black voters. But I can’t imagine that a serious effort to try to unseat the incumbent president would encumber itself with such a divisive and ethnically partisan policy. I’m against the reparations rallying cry. I really am. I have practical reasons: Who is a black person? Who is entitled? I have political reasons: You think you’re going to win an election with that? I don’t think so. People who are opposed to reparations or racists? That card works really well in the Ivy League campus setting where I live, but I happen to think, out here in central Pennsylvania, it’s not going to fly. And I think that’s where the election is going to be decided in the year 2020.

How about this? How about those who are concerned about the lasting effects of slavery and Jim Crow as they manifest themselves in the lives of very poor and disadvantaged and marginalized people, how about if we get about the business of building a coalition of poor, disadvantaged, and marginalized people of all races, and try to formulate a politics in which the essential needs of those people for opportunity would be at the center of our advocacy? I am prepared to include white people, brown people, yellow people, red people, as well as black people in that effort. That would be, I think, a serious American political enterprise. This sectarian enterprise—“Y’all disadvantaged my ancestors and I need to get paid”—I don’t think it’s going anywhere and I don’t think frankly it should go anywhere.

Very well said.

When Dr. King was active I, as a student, leaned towards those voices who cried for more radicalism; but now, 54 years after Dr. King's death the devastation brought by that radicalism, and the poisonous Wokeness it has led us to, prove that he was right all along.

This is where I part from Glenn. I have the utmost respect for him, but in my view these programs should NEVER have been implemented. The purpose of the state, of law, is to uphold the inalienable and to ensure that law is applied equally, to everyone, everywhere. You cannot ask the law to plunder because its expedient, then ask it to stop plundering when its not expedient. You don't right a wrong by creating another wrong. That is a dangerous game..

These programs were never equitable, because nothing can justify using someone as a means to an end, and that's precisely what quotas do.

Granted, blacks were not given equal rights under the law for a long time, but asking people to pay for the crimes of their ancestor is a dangerous proposition. You don't want the law to place people into groups. If you go down that path, then it won't be long before the state investigates everyone's background, and seeks to identify and force reparations on those with an ancestor -- any ancestor -- who has committed a crime. People must be treated as individuals.

And blacks won't escape that type of historical culpability, that type of legal strangulation either, because there were black slave owners, black slave traders, so on and so forth.

Merit and examinations are the only way to ensure fairness and justice.