Colorblindness in the Public and Private Sphere

with John McWhorter and Coleman Hughes

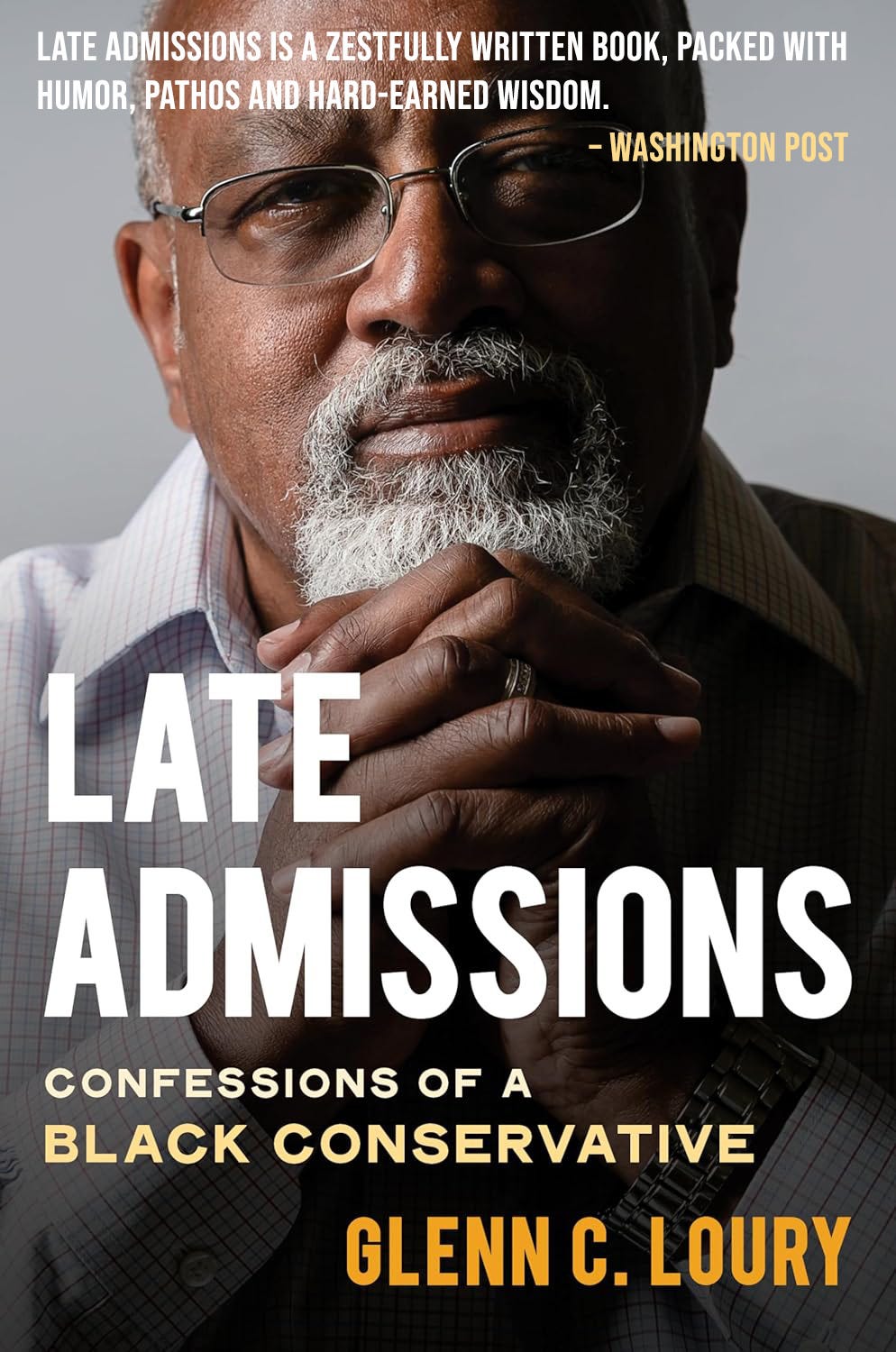

Coleman Hughes’s book, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America, has provoked a lot of discussion here and elsewhere. Though I have all the respect in the world for Coleman and his ideas, and I think his prominence is a net good for our racial discourse, I have some misgivings about his argument. Some of these misgivings, I have no trouble admitting, derive from my own particular history, upbringing, and social and intellectual development.

There’s an eagerness in his book, and in the work of others in his wheelhouse, to place a strict cordon between the racial public sphere and the racial private sphere, where racial identity could be given free rein in the latter while being effectively legislated out of existence in the former. As he says in this clip, we should be free to do as we choose in our private lives—even if that means intentionally associating only with our own co-racialists—while race would have no “official” existence in our politics, policy, business affairs, and so on. There would be certain exceptions—no one should want to tell the Yemeni bodega owners they’re being discriminatory by hiring their cousins—but for the most part race would cease to exist on America’s balance sheets.

Some of my misgivings about this position are technical in nature. For example, if we want to ensure that publicly funded universities aren’t systematically giving preference to African Americans over more qualified applicants of other races, some agency would have to track the numbers and note each applicant’s racial self-identification. In other words, we would have to keep race in the public sphere in order to keep it out of the public sphere.

But the real core of my objections have to do with how we conceive of ourselves as social beings. We’re born into vast, complex social networks of families and communities and institutions, parts of which have an explicitly racial or ethnic dimension. These networks foster and shape us. They make us who we are. They influence our political self-conception. And sometimes that self-conception, too, will be explicitly racial in its character. As much as I want a future where our collective racial history won’t weigh so heavily on our self-understanding, I wouldn’t want a future in which we’re completely divorced from that history and the traditions it has birthed. Can we really keep those traditions alive in the private sphere without feeling their effects, however subtly, in the public sphere? Can we stop those traditions from influencing, say, how we behave as political actors? I don’t think so. And I wouldn’t want us to.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

COLEMAN HUGHES: I think in general in life, you should think about your privileges. You should think critically about them. Have you benefited from the fact of your race? Have you benefited from the fact of your gender? Have you benefited from the fact of your socioeconomic standing? These are all questions that you should engage critically with as a person in the world. Say you're a white guy born in a single-parent home with a drug-addicted parent. If the honest answer to that question is, “Actually no, I don't think I've benefited particularly from my race,” then you should stand by that.

When people say you should reflect on your race, often what they mean is you should automatically feel guilty because you're a white person, regardless of what your individual story is. I think you should reflect on your individual story and try to be very honest with yourself and with the world. But you should not automatically go into this pat formula of white equals privilege, white equals bad, black equals victim.

Can I be honest about the fact that it's much better to apply to college as a black person? For me, part of my being honest about the influence of race in my life is not to accept the simple narrative that I'm supposed to invite, but rather to be honest about the full spectrum of effects that race has had in my life and race has in others. And to me, my argument is compatible with that kind of a conversation, given that we all are able to enter this conversation as equals, we're all able to participate in it, and you can be at the table as a non-person of color and you're not going to get shut out.

One thing, actually, people do say frequently and people said at TED reacting to me—besides your comment, John, which I get a lot—is “Look, I'm just a random white guy, so I don't know. I really shouldn't say anything about the topic.”

JOHN MCWHORTER: They've learned their lesson.

COLEMAN HUGHES: They've learned that anything they say is the wrong thing to say, and that almost bothers me more.

GLENN LOURY: I'm struck by the use of the word “should” in your recounting of the experience and in your brief summary of your argument. “Should.” It's a moral, philosophical position—“should”—and I'm contrasting that with the meta-analysis that you mentioned briefly, claiming that colorblindness has certain consequences or doesn't have them in terms of advancing goals that one might think are socially desirable.

Can you address yourself to this distinction between the moral argument and the causal consequences argument and tell us how you think about that?

COLEMAN HUGHES: Yeah. As I think you guys know, I was a philosophy major, and I was always attracted broadly to the idea of consequentialism, which is that the “shoulds” in life stem from what the consequences of actions or even rules are.

So broadly, certainly in America, I think the consequences of colorblind policy in the long run will be better than the consequences of race-based policies and race-thinking in general, an obsession with race-thinking in general in the long run. And that's my impetus to write the book.

I'm going to push back.

COLEMAN HUGHES: Okay.

Voting rights. We're drawing congressional districts in Alabama or South Carolina. The question is whether or not black people are going to have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice. Is that a completely incoherent or morally dubious conversation for you?

And by that, I don't see how I can get off the ground in that conversation without, A, classifying people based upon their racial identity, B, imputing, to some degree, a sense of representativeness when the race of the elected official matches the race of the person casting the ballot, and C, implementing on-the-ground enforcement mechanisms to ensure that, in fact, those people whom I've decided to see as blacks get to elect a representative of their choice.

So how do you square the historical imperative of, in the case at hand, empowering African American voters, given our history, with your position on colorblindness?

COLEMAN HUGHES: Yeah, so that's a good question, because I think that in the case of voting rights and district drawing in general, what you get is one side trying to strategically separate heavily black districts and disperse them among many districts, and then the other side saying, "“I see what you're doing there, and you're trying to strategically dilute the power of a voting bloc that is recognizable and trying to prevent them from doing that by drawing the lines more closely around the voting bloc.”

In some way, both sides are playing on the concept of race. Both sides require the concept of race to achieve political ends there. And so it seems to me valid for Democrats in this case to say, “Look, I can see you trying to dilute the power of black voters in Alabama not because they're black but because they're the most reliable Democrat voting bloc. That's anti-democratic gerrymandering, and we have to be able to push back against that.”

I guess that one case doesn't necessarily extend to the other kinds of race-based policies I'm talking about in the book. For instance, race-based affirmative action, race-based emergency aid during COVID, deciding which restaurant should get aid based on the racial identity of the owner as opposed to the socioeconomic need of the restaurant.

You bring up a good example, but I don't think the lesson can be drawn from it that race based policy in general is wise or good.

Okay. What about the distinction between colorblindness in law and policy and government action, on the one hand, and colorblindness in terms of personal affiliation, choice of intimate partner, identity in terms of how I narrate the history of “my people” and all of that? Do you find that to be an at all useful distinction?

COLEMAN HUGHES: Absolutely it's a useful distinction. I think that if you are a person that says, “Look, I agree with you that there should be no race as a category on which to base social policy. But in my own life, I'm black or I'm Korean or I'm Jewish, and I, to be perfectly honest, prefer to be with my own. I am going to marry someone that is of my culture. Most of my friends are of my culture. I have nothing against other cultures, but it's where I feel comfortable and it gives me an identity. It gives me a story. And this is the story of my people, and it has meaning for me,” I think that there's not much I can say to such a person, because they agree that it should be kept out of the public sphere in a way that it should be kept out of public policy and should be a private thing.

If I go to a deli in Harlem, and everyone working at the deli is Yemeni, they're not hiring colorblind. Do I have a problem with the Yemeni deli owner that only wants to associate with other Yemenis? No, not really. Personally, I live a pretty cosmopolitan life, and I would defend the cosmopolitan life in the sense of, I have friends of every race, and I like that.

I like that I'm open to having friends of every race and associating from a place of “Coleman as an individual” as opposed to “Coleman, a raced person.”

JOHN MCWHORTER: I don't think that's the human default, though, Coleman.

COLEMAN HUGHES: That's right, I don't think it's the human default, and I don't judge as immoral the people that have a strong attachment. What I would want them to do is observe the distinction that you just made. It's fine for you to have that in your own life, but let's draw a bright line between your personal, private decisions and private values and what should be included in public policy.

JOHN MCWHORTER: Suppose they're white, is the question. Suppose a white person says, “I like my people.”

COLEMAN HUGHES: Look, to be consistent, if they're living their own life and not insisting that there be pro-white public policies, how are they hurting me?

I think I can hear Black@TED calling right now to answer that question.

JOHN MCWHORTER: Because suppose you need a job. Suppose it's like a white chain store. Suppose it's Target. I think we've gotten to the point that Target would never have such a public policy, but suppose this denies you opportunities for employment. It's a relatively thinly settled, small town area and the whites ...

Let me just mention, John, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, I'm pretty sure has a minimum number of employees, where it doesn't apply below 15 or something like that.

JOHN MCWHORTER: Is that true?

So if I'm opening up my Yemeni bakery or my mom and pop bodega, it doesn't apply to me, and I can be preferential in my hiring policy.

COLEMAN HUGHES: I didn't know that either. That distinction makes sense, because it's the reality or there's some deeper wisdom to it. You have a big chain store. To have them rejecting every black applicant, to have Walmart rejecting every black applicant, it just … it wouldn't make sense for so many different reasons. But it doesn't bother you to see a mom and pop shop where everyone is even in the same family, much less the same race.

JOHN MCWHORTER: Is there really a Yemeni deli in Harlem?

COLEMAN HUGHES: Oh, many, many.

JOHN MCWHORTER: I didn't know that.

COLEMAN HUGHES: When I was at Columbia, I would make a point of microaggressing every deli owner by asking where they're really from. And the Yemenis don't mind, but almost everyone to a one was from Yemen, specifically. And I thought that was interesting, because it's a country I knew nothing about, a rather small country, and yet they own and operate a huge number of delis in Harlem.

JOHN MCWHORTER: I didn't know that had become a thing.

Yeah, an ethnic enterprise. One thinks of the Vietnamese nail salons or the Korean green grocers or whatever. And there's a whole backstory about social capital and how people pull together and finance and mutually support each other within their identity-based social networks, which are economically valuable.

COLEMAN HUGHES: And by the way, this is when I was heavily reading Thomas Sowell in college. And so I felt I was coming across an obvious real-life example of a sub-industry and then part of a city that was just dominated by one ethnic group. That became interesting to me. So I always made a point of asking. And it wasn't Arab in general. It was always Yemeni.

Glenn asks, " As much as I want a future where our collective racial history won’t weigh so heavily on our self-understanding, I wouldn’t want a future in which we’re completely divorced from that history and the traditions it has birthed. Can we really keep those traditions alive in the private sphere without feeling their effects, however subtly, in the public sphere?"

The answer is transcendently simple: of course we can't; nor should we. We cannot separate & segregate our understanding of the world. We can only try to not allow our natural predilections, our inherent preferences, our likes and biases to significantly & unethically influence our decision making when it comes to hiring, firing, promoting, critiquing, electing, and recommending the Other.

I, as a for instance, have a special fondness for red-headed women. As a category I find myself more naturally attracted to them. In fact, I'm married to one of them. I have, as they say, 'history & traditions' with red-haired women and I absolutely plan on keeping those traditions gloriously alive in the private sphere as much as I can.

And yes, at the same time, I feel their effects even in the public sphere.

The difference is, I'm well aware of my built-in bias in that regard and I make a special effort to NOT allow that bias to dictate my decision-making. (In any way, that counts). I may favor the red-head girl's checkout line at the grocery store (because I think, quite naturally, that she's cute)....I may select a Nicole Kidman film more often than not...but when it comes to hiring, firing, promoting, or praising I'm particularly careful to separate my evaluation of a performance or a candidate from my natural leanings towards redheads. I would hope & expect that Glenn & John do the same, re: Blackness.

Glenn suggests that, "we would have to keep race in the public sphere in order to keep it out of the public sphere." But this is simply not true. In order to keep public universities from being racially biased in admissions, you don't need to track race, you simply need to stop counting it at all. Remove it from the admissions forms the same way we've removed any mention of Irish Ancestry or whether one is a Star Trek Fan. Wait...you mean Irish Ancestry & Fan Affiliation has NEVER been a box checked on admissions forms? Fancy that?!

Glenn tells us, "The question is whether or not black people are going to have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice." The answer is self-evident. Of course they will...the same way white people, brown people, red & yellow people all have an opportunity to elect a representative of THEIR choice. Whether that opportunity produces any particular victorious candidate is an entirely different question that only a total vote count answers ... but everyone who votes has that opportunity.

Glenn's actual concern is much narrower, though, as he additionally asks, "(whether) the race of the elected official matches the race of the person casting the ballot." The answer should be: who cares? I certainly don't. I've never cared whether the color, the sex, the age, the generation, the height, or the weight of the elected official matches mine in any way at all. Why should I? When we elect a representative we want them to represent OUR INTERESTS not our skin color or genital configuration. And to assume that everyone who shares a demographic marker ALSO SHARES my interests is both insane and racist/sexist. Of course they don't. I'm surprised, actually, that Glenn would even ask that question.

Mr. Hughes goes on to tell us, "I think in general in life, you should think about your privileges. You should think critically about them." But what the heck is privilege anyway?

We might say that whatever we have which is unearned is privilege, I suppose. Certainly skin color is an unearned quality. But so is height. So is beauty. So is grace. So is everything contained in the genetic luggage handed us by our parents at conception. And so is the life we walk into at birth: our parents' economic condition, our house, our brothers & sisters, the neighborhood, the church, the schools, our families, the music we listen to. None of these things WE earned; rather they were all given or made available to us. I suppose, per Mr. Hughes, we should think critically about all of that. But .... equally we might think critically about our burdens, the various crosses we all carry (that we did not earn or somehow deserve)...and then net out the good & bad and see where we end-up.

But honestly, doesn't that sounds like an immense waste of time & effort to arrive only where we began, feeling both bitter and pleased (I don't have that...but I do have this?!....grateful and envious?).

Perhaps we'd be better off if we simply made an effort to understand that every single one of us has MORE than someone else....AND every single one of us has LESS than someone different. As children we tend to celebrate the one (Yay! I'm faster, taller, prettier, stronger....) and bemoan the other (Booo! I'm slower, fatter, uglier weaker....). But as adults, isn't it time to put these childish things away?

The question is not difference / advantage. The question is: what are you going to do with what you have, whatever that is.

John asks, "Suppose a white person says, “I like my people.” The answer is 'So what?' Who cares? Why does it matter? We can choose as friends anyone we wish. That can look anyway they like. Thank God the State has nothing to say about any that. Thank God we don't have DIE Friendship Mandates.....or Demographic Diversity Targets for Dating.

The problem that we're finally beginning to recognize: neither should we have them for anything else....as Mr. Hughes, I believe, understands.

Your monthly Q&A would be much more worthwhile if Mr. Hughes were to replace McWhorter. JMcW no longer has any credibility as a thoughtful and intelligent conversation partner, while Mr. Hughes does.