Don't Worry, I'm "One of You"

The constraints of free speech

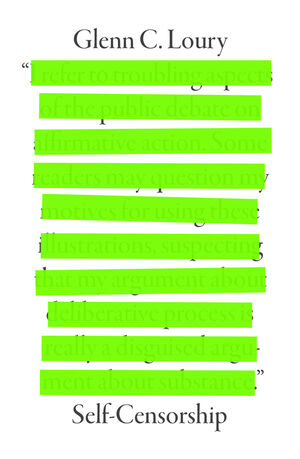

In preparing the manuscript for my forthcoming book, Self-Censorship, I revisited not only the 1994 essay, “Self-Censorship in Public Discourse,” that takes up the bulk of the book, but other versions of that text I’ve delivered as lectures. The idea for the essay first occurred to me in 1987. In the seven years between inception and publication, chunks of the essay appeared and disappeared, I tinkered with this section and that, and I wrote many drafts. Even after I had the final draft of the essay, I would hit different points of emphasis when I spoke about the text.

There’s nothing unusual about that. What was unusual was the strangely self-reflexive quality that emerged when I delivered lecture versions of the essay. “Self-Censorship in Public Discourse” is, in part, about the dilemma faced by speakers who wish to communicate a potentially unpopular message to an audience without drawing negative ad hominem inferences from that audience. The speaker must signal to the audience, using various subtle strategies, that he is “one of them” or risk losing his audience.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

All well and good, in theory. But I at some point realized that I was actually doing the thing that the lecture was describing as I was delivering the lecture itself. I had to deliver the lecture, which argues, among other things, that truly free speech is a social impossibility. We’re all inhibited, not by the law but by the constraints imposed by the potential negative social consequences of saying unpopular things in front of an unreceptive audience. In this version of the lecture, which I gave at the American Enterprise Institute in 1994, you can see me attempting to manage this exact problem. For those who don’t know, AEI is a market-friendly think tank. I was affiliated with it for years, and fairly involved in the organization, until I quit. (You can read all about that in Late Admissions.)

Here’s an excerpt from the lecture:

Let’s suppose that a certain member of that community thinks it worth entertaining at least, the prospect that relaxing the trade embargo with Cuba would actually be a positive boon for the development of democratic institutions on the island.

I hope you understand, in my presenting this example, that I have no brief here about Cuba. That’s the reason I’m talking about that question and not some other. All right. I mean, I hope you see that the problem that I’m discussing is with us all the time, even right here in this lecture room.

That is, even though I might presume at the American Enterprise Institute, that I have a relatively sympathetic audience, I can never entirely relinquish my own strategic calculations about what motives you might impute to me from my own choices, even the choices of the examples that I use to illustrate the ideas that I’m trying to convey to you.

And as I want to be effective, I want to be heard by you, I want to get past all of the possible barriers to effective communication, I’ll select an example, to start out with, that’s at some distance. I have no position on the Cuban question.

But within the Cuban community, immigrant community of South Florida, the act of opening the question of whether or not Mr. Castro’s government should be permitted some more friendly economic relations with the United States is not just to make an argument. It’s not just some exercise. It’s an expression that raises profound questions of who is the person who’s saying this, and how do they relate to us? Do they share our deep commitments?

Do they have any idea, this young twenty-nine-year-old whippersnapper down here from the Harvard Business School, now talking about opening up trade relations with some abstract foreign relations argument, some theory about the interaction between markets and democracy, do they know the price that was paid by those of us of the generation who were run off that island?

So the ability to carry on a discourse within that community about this particular question might well be understood to be impeded by the meanings with which any such argument will be freighted.

[…]

I’m simply noting that in the game of public discourse—it’s the game, the interaction where some of the motives are hidden, where a player can lose if he’s not careful—that in that game this kind of phenomenon, this kind of reading between the lines, and “writing between the lines,” in [Leo] Strauss’s memorable term—all right, this kind of calculated framing. How will I present the idea?

Notice my caution when speaking to this audience at AEI about the Cuban embargo. Why am I so careful to emphasize that I have no position on the Cuba question? Surely, in 1994, I had something to say about it, even if it was just a vague sense of whether the trade embargo was justified. Why this coyness, even before a friendly audience?

Even when “among friends,” the exigencies of self-protective strategies hold. Most of my particular audience at that moment—AEI—had a probable position on Cuba, which was to keep the embargo in place. My wink to my audience is almost audible: I have no position on Cuba ... but, after all, I'm “one of you,” and if I did have a position, you wouldn't be crazy to think it was in line with that of the average AEI member. In fact, I'm almost inviting you to infer that it is.

A careful reader of “Self-Censorship in Public Discourse” will note that this is not a random example, but one calibrated to shore up the very in-group bona fides necessary to avoid negative ad hominem inference. Now, why should this be necessary? I’m “among friends,” after all.

But an audience is never really your friend, not in the way that, say, an old high school buddy is a friend. I may have had real friends in the audience (in fact, I did), but the reaction of an audience obeys different incentives than that of a friend. No, I was among ideological allies or political allies or colleagues or others who, whatever their personal affection for me, are in this context functioning as representatives of an institution to which a certain degree of fidelity is expected. ‘Twas ever thus. This is the way of the world.

Institutional imperatives—using the term “institutional” loosely—can, when ideological conflict is on the line, drastically affect the way a message is received. If a speaker’s message violates a shared belief of his audience—and think tanks are often organized around broadly shared beliefs or ideological premises—he may find himself on the wrong end of adverse ad hominem inference. We've all probably heard someone whose views we thought similar to our own say something we think is deeply mistaken. We may think, “Wait, he's not saying what I think he is, is he? I thought I knew him.” In that moment, our opinion of that person can flip. Maybe we didn't know him at all. Maybe he’s not “one of us.” Maybe we were wrong to extend him the benefit of the doubt.

Our friends—our true friends—forgive us our ideological transgressions in the name of love: “Sure, Glenn’s wrong about X and Y, but he’s a good guy. Cut him some slack.” But once we step outside that protective circle of intimacy, anyone who transgresses against their “own” audience’s core beliefs risks becoming a pariah. We see this happen regularly to those who violate their institution’s company line, whether that’s a university or a political organization or a think tank.

This isn’t a partisan point. It’s about the nature of institutions and, really, of audiences of all kinds. One must always remember to wink and write between the lines, to signal that, whatever is said on stage, the speaker is really “one of us.” That’s what I was doing on that stage in 1994 when I mentioned Cuba, whether the audience was conscious of it or not, even as I was explaining why such a gesture was necessary. It’s what we all must do. If we don’t, if we fail to cater to the crowd, we may find that the next time we get on our soapbox, no one will show up to listen.

I don't think it's Cuba that you mean here...

I have been thinking about my self-censorship after recently watching some presentations on censorship and self-censorship in sciences (https://dornsife.usc.edu/cesr/censorship-in-the-sciences-interdisciplinary-perspectives/). As a physical scientist, I probably have a greater focus on data than economists and other social scientists, who seem to rely more on argument, theory or history. I have generally found carefully measured data to be more persuasive than narratives. I naively think others will also find data to be persuasive. My approach to presentations and writing is to highlight and explain the data, not my opinion. No sugar coating. Whether an audience is on my side or not is irrelevant. Whoever they are, the important thing to me is that people see and understand relevant data. This may be why I am not invited to give presentations very often. And that is fine with me. This may help me minimize self-censorship, at least in professional settings.