Finding a Path to Progress

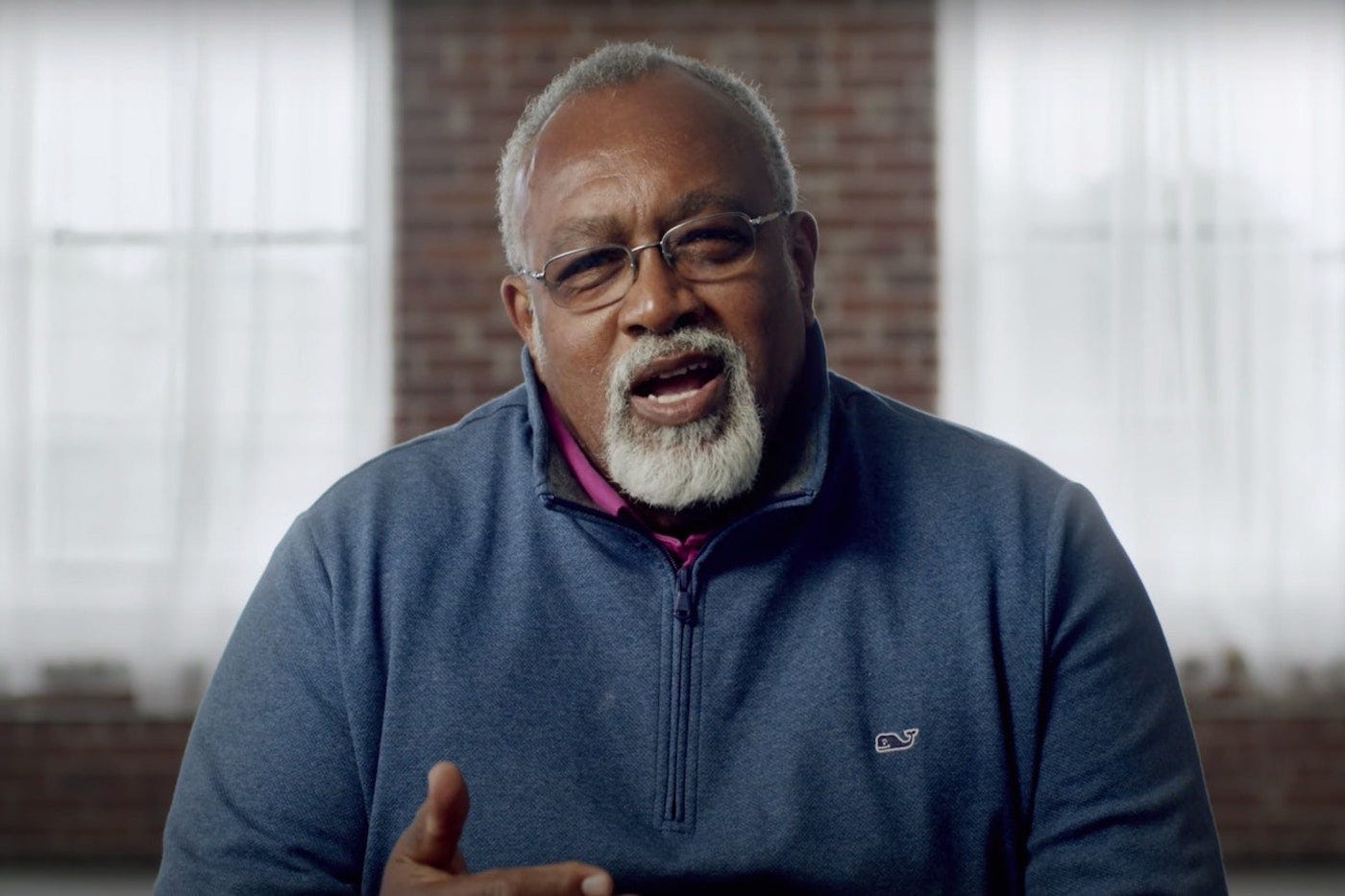

A conversation with Alexander Riley

Earlier this year, I sat down to talk with Alexander Riley, who is a sociologist at Bucknell University and a contributor to Chronicles magazine, among other outlets. Alexander asked me a series of probing questions that gave me an opportunity to reflect on nationalism, the family, labor, and religious institutions. As I see it, these are not entirely separate facets of American life. Rather, they’re deeply entwined with each other. When one begins to weaken, that change has consequences for the other three.

It’s hardly an original observation to note that, since at least the 1960s, all four of those domains have undergone massive changes. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, Vietnam, the rise of “knowledge work,” the Great Society, feminism, increasing secularization, the list could go on. Below I offer not a detailed social/economic analysis, but a broad survey of some of these changes, and some of the deleterious effects that have followed from them.

Don't misunderstand me. I am not pining for an idealized, earlier, “greater” America. Not at all. Rather I want to ask if some of the decisions we have made and patterns we have adopted as a nation will serve us as well, and allow us to prosper as much, in the future as has been the case in the past. It’s not clear to me that every “progressive” social development will, in fact, lead to progress. Real progress, in fact, requires us to be openly self-critical, and to find ways to remedy some of our missteps. (Alexander recently published part of our interview, but I’m presenting the whole thing here.)

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

ALEXANDER RILEY: Your First Things piece makes a case for black patriotism. Let’s talk a bit about the practical necessities of getting the country to the place where more Americans of all racial and ethnic groups think outside of the identity categories that have become the first way many people think about who they are. How do we move toward “All of us Americans, together, with a common project and common goals we’re trying to get accomplished”?

GLENN LOURY: You're asking me for solutions, and it's much easier to diagnose than it is to cure. I’m not sure I know the answer. It’s a big question. It seems to me that the puzzle here is why there isn't more of a class based framework for aggregating a progressive or liberal or reformist sentiment which unites the interest across racial lines of working-class and lower-middle-class and struggling people. For example, the Democrats now are playing this “election integrity versus ballot access” card and they color it in racial terms. They say, “Martin Luther King, John Lewis, freedom to vote.” They say, “Unless we have elections with a certain amount of lead time for early voting and a certain amount of liberality of access to the mail-in ballots, we are not getting racial justice.”

That strikes me as a problem crying out to be addressed. Isn't it interesting that they frame it that way? We could quibble about who should have an ID when they cast a ballot. I think some of these questions are arguable. It's far from clear to me that it is a violation of the spirit of our ideas about equality of access to the ballot to require identification. But be that as it may, they frame it as a racial affront. How is it that it has come to that?

I think there's a huge vested interest in the left of center political establishment in mobilizing people to vote Democratic based upon a perception that their vital political interests as persons of color are best protected in that way. Their vital political interests, recognition of their membership in the polity. And I think that promotes identity politics. I'm just in a way crudely trying to rephrase Mark Lilla’s argument in Once and Future Liberal. He says identity politics is Reaganism for lefties. That's a quote from that book that I really love. He means that Reaganism is laissez faire. It’s every tub on its own bottom. It's “I got mine, fuck you, Jack.” And the left’s version of that is: “I'm black, you're gay, I'm trans, you're a woman, and each of us is going for our own ethnic or racial or identity interests as opposed to going for some broader conception of our social interest as members of an economic class.”

George Floyd gets killed in Minneapolis. He's a black man killed by white police officers, and there's a lot of different ways of narrating what happened there. Police with too much power, citizens without access to mental health care, accountability structures that no longer incentivize the right kind of action, etc. But it gets narrated as Emmitt Till! How did that happen? That was a sleight of hand that it behooves us to reflect upon for a moment. There's a huge amount that's at stake there. Cities ended up burning because of the way that that event was narrated. There are some people who are doing the statistics to argue that it's costing thousands of black lives because of police reaction and the change in the way in which order is being maintained or not maintained in urban areas and the amount of violent crime that is being committed. That was a very consequential thing that happened there.

Now who had agency? I'm talking about the press, I'm talking about political leaders, I'm talking about freelance demagogues, I'm talking about lawyers who are bringing lawsuits against municipalities. These are key players in the framing of the whole thing. I would look to something like that as a source of an explanation for the stubborn persistence of this kind of politics.

You also touched in that First Things essay on the Tocquevillian question of the role of mediating institutions in addressing some of the problems that we're facing. Two specific examples you discussed were religious institutions and the family. How do you see the weakening of these two mediating institutions contributing to problems of racial disparity and also to broader social dysfunction in American culture? What role can religion and family play in helping fix existing social problems?

Here I follow James Heckman, the economist at the University of Chicago, and human capital theory. In an old Daedalus essay from 2011, Heckman asked what we know about the structures that facilitate the acquisition of the skills and the habits and the orientations that allow people to be successful in life. You might measure success by educational attainment or by occupation and income or by avoiding certain negative outcomes like imprisonment. What seems to be the pathway that successful individuals follow? Education is a part of that, and also the acquisition of, if you will, civilizing habits of self-discipline. There’s a literature in the social sciences on this, and Heckman is prominent in it. He pulls together the numbers and shows that family matters, not just for income and the acquisition of hard skills, but also for soft skills like self-restraint that he believes are important to determining later life success. This is the context in which a person’s developmental roots get sent down, and in which the framework for their maturation is built, their acquisition of skills, orientations, and habits that are of value to them in their adulthood.

We see a number of things today with family structure—out of wedlock births, mother-only households, multiple partner paternity. My friend and colleague Robert Cherry, the economist emeritus from Brooklyn College, shows it’s not just a problem of single parenthood. He says that multiple partner paternity is a big deal. The woman has children by more than one partner, so she may be not living with any of the partners and so the investment that the father might be inclined to make in his child by transferring resources and time to the household where the child is being reared is attenuated by his anticipation that some of what he supplies at least in terms of financial resources might not redound to his kid. So he doesn't know whose child is given the benefit of his contribution.

That's a very economistic way of looking at it, and I'm not married to it. But the family is the context within which early development of human potential is undertaken and that problematic character of structure in African American families in comparison to others is certainly part of the account you'd have to give for persisting racial inequality. That's an argument I've been making.

And it’s a fair point that, as you hint in the question, there are problems in the family more broadly. Divorce is up historically, the norms of marriage before reproduction have weakened, women are working, feminism. Go back 75 years and there's one kind of regime in terms of division of labor within households. Fast forward to 1970 and things have really been begun to change quite a bit. Norms have weakened, expectations are different.

A question that has been asked since the ‘60s has to do with whether the liberation of women from the constraints of conventional assumptions about their roles especially within households has been good or bad for children. These are empirical questions and I’m hesitant to speak of them without knowing the data very well. But we have liberation at the personal level, freedom from the burden of conventional constraints about roles and behavior regarding sexuality and sexual identity, and also regarding gender, obligations to children, and marital stability. What does that imply for children? “I'm gonna do my thing no matter what, I’m gonna do me!” I don't know how that's good for kids.

So the racial disparity here becomes a glaring thing, but it's nested within a larger question. You could make the point that the real driving forces here are far larger than “black culture.” Racial disparity is really only a derivative result of the larger social abandonment of a set of norms which manifests itself most immediately and most severely in the African American population, but which really is a larger atmospheric that's developing for all of us.

What about religion?

The reason the church is important is because we're trying to govern individuals at the normative level. We're trying to get them to embrace ways of life. And that's just politically and ethically infeasible for a state to do in a pluralistic society. So we need centers of authority that have enough leverage to be able to reach people and, as it were, train them or form them in ways that you can't do in the public schools or through the tax policy. We have a certain neutrality, and we can't affirm any particular way of life, but it's critical that people embrace particular ways of life. They don't have to be the same. They don't have to be reading from the same hymnal, but they need some sources of authority that are robust enough to allow for a shaping of these persons who are going to be breadwinners and parents and citizens.

Participation is voluntary, so that helps to ease the problem, but in the absence of that intermediate structure of authority, you get a very thin framework. It has to accommodate every different possible perspective and hence it doesn't have very much traction at all. How am I going to keep a kid from getting pregnant? What am I going to teach them in sex education? Just the mechanics of the biological processes? I can finger wag about using condoms, but I can’t teach him anything that's really strong, that gets them in embracing it to withhold from impulse because they are trying to adhere to an understanding about what right living is. An understanding about right living can really only be effectively conveyed through the mediating structure.

In your responses to all these problems of American culture, you’ve been remarkably consistent in noting a central truth about them: While blacks are perhaps inordinately negatively affected by familial decay or the drop in real religiosity or the increase of criminal violence, these are American problems that have harmed all groups in the US. You have also frequently noted in your writing and other public interventions that this makes possible a recognition by folks with profoundly different ideological orientations that there might be robust ground for cooperation across ideological lines precisely because the problems are shared in this way and not limited to just a racial lens. Could you say a word or two about that?

I’ll give you a concrete example of this. I have cited Adolph Reed, a formidable thinker on the far left, in defense of my position against framing social inequality issues in explicitly racial terms. I’ve been chided by some friends for this. Now, Reed and I do not share the same political philosophy. I am not a Marxist. Indeed, being a more or less orthodox economist who thinks markets work reasonably well most of the time and who appreciates the role played by property rights, self-interest, and incentives in promoting economic prosperity, I am probably guilty of some affinity for what many (including Adolph Reed!) refer to derisively as “neoliberalism.” Still, Reed’s attachment to historical materialism in the tradition of Karl Marx notwithstanding, one can understand his critique of anti-racism politics without embracing Marxism.

I wish to call your attention to the work of the sociologist Rogers Brubaker, particularly his monograph Ethnicity without Groups. There, detailed attention is given to the incentives of racial or ethnic entrepreneurs to manipulate identity concerns for their own careerist and ideological interests. He focuses on the decision about whether to frame multifaceted social conflicts in racial or ethnic terms, and explores the implications of such framing decisions. Brubaker’s way of thinking about the racial advocacy enterprise provides a non-Marxian conceptual foundation for Reed’s (and my) criticism of identity politics. It views claims about racism critically, not as the natural and inevitable reaction to some overarching and inexorable historical racism, but rather as the ongoing, politically and socially constructed consequence of the choices made by strategic actors who elect, for their own benefit, to use “race” as the defining framework for understanding social problems and mobilizing political action.

Thus, to give but one example, I wish to note that twice as many whites as blacks are killed by police in the US each year, many of them under some of the most egregiously unjustifiable circumstances, circumstances that would rival the most celebrated cases of black victimization. My point is this: Building the current movement for police reform in explicit and predominantly racial terms is not a natural historical inevitability. Rather, it is a mistaken strategic choice that has had profound consequences.

What is more, doing so while insisting that people must also ignore racial disparities in rates of criminal offending and intra-racial violence, lest they risk being accused of racism, is an especially consequential “framing” move—one that I believe is, ultimately, not in the interest of black people, properly understood. Black activists calling attention to the race identities of a cop (white) and an unarmed young man (black) caught in violent confrontation invite other racial frames to be employed when (white) people turn their attention to matters of law, order, and policing, etc.

I could give other examples, such as framing the immigration policy debate in racial terms, with those wanting stricter enforcement against the unauthorized entry of low-skilled migrants being accused of “racism.” This obscures the complex and multi-dimensional nature of black Americans’ interests in relation to this issue.

So there is no contradiction between my being a “neoliberal” economist and my appreciating the trenchant criticisms that Adolph Reed provides of the dead end that is today’s racial identity politics. Plenty of room for common ground here.

What are your thoughts on the racial politics and the stance on American patriotism behind something like the 1619 Project?

I look at the 1619 project and at the spirit behind it, Hannah-Jones and the others, and I say this: Okay, the country is flawed, sure, but we have the benefit here at the start of the twenty-first century of being birthright citizens in this great Republic. That’s a huge entitlement. Why would you stand apart from that? We're practically an indigenous population here now, centuries on in the United States. How do you expect that you are going to get anywhere politically if you stand apart from it?

Your interests are much more effectively served by finding ways of joining your project with the American project. Isn’t this what King and company do with their “magnificent promissory notes” and their “I have a dream that one day my children etc.” and with their strategy of embarrassing the country by exposing Bull Connor for what he is, and in calling us all to the higher ground? Join your project to the national project, which means affirm the national project, which means acknowledge the nation.

So when it comes to border control, and I don't take a position here about who should or should not have asylum, I simply say that this set of issues cuts across the issues of African American membership within the American nation. You want to join up with the people from Central America and label us all in an intersectionality move as “non-whites,” and then call these guys who want a border on the Rio Grande “racist”? They’re not racists, they're nationalists. And by the way, they're nationalists on behalf of the same project that you should be affirming.

The brownness of those people is so superficial. That’s a racially essentialist move. You black advocates, and I'm speaking about practically every single member of the Congressional Black Caucus, you are making a racially essentialist and politically counterproductive association between the centuries old historical claim of African Americans on the attention of the nation and that of people who want to walk across the border into the country without authorization. May God love them, I'm not against those people. They simply happen not to be a part of the historical dynamic to which I'm trying to call attention.

And the other group there whose interests those advocates are supporting in that move are the business elites who are harming economic outcomes for poorer Americans while they save money on their labor force.

Isn't that ironic? They’re not planters on plantations anymore, they're agribusiness. But they still need their crops picked!

This reminds me of that wonderful interview you did several years ago with Harvard’s George Borjas on your podcast. Borjas wrote what is in my view one of the most important books on immigration for a general audience, We Wanted Workers. The two of you talked about this profound political problem that it's so demonstrably obvious that our current immigration policies are not helping the poorest Americans, which includes a disproportionate number of blacks, and yet it's nearly impossible to find black public figures on the left who even recognize the point you and Borjas were talking about.

And by the way, that podcast discussion comes 15 years after I first met George Borjas, when he was teaching in the economics department at the University of California, San Diego. I remember sitting down with him and him telling me, “You are the only person in the profession who can say this.” That's not quite literally true, but he was saying “You're black, I'm Cuban, and they’ll cancel me. But would you please say it because the numbers are telling me that it's a very serious issue.” And that was in the ‘90s.

Roger Waldinger’s wonderful book, How the Other Half Works, has data from Los Angeles on all these different industries—hotels and restaurants, hospitals, furniture manufacturers, construction—and it has interviews with employers and workers. Part of what he's documenting is how new employees are recruited through social networks that are heavily influenced by connections between Mexican employees and new immigrants. So a Mexican immigrant Manuel who came from a certain village knows someone already employed at the site, or it’s his second cousin from that same village and so Manuel ends up with the job. The book also looks at what language is spoken in the workplace. Frequently, it’s Spanglish, or large amounts of Spanish, and black workers are disadvantaged linguistically and they're kind of displaced. It’s more than just the aggregate statistical stuff that Borjas does. It’s much more descriptive of the actual processes that are at work.

An interesting point Waldinger makes is that if you're in a hotel room, you're in your underwear and the maid knocks on the door, if she is a woman who's 5’2” who speaks little or no English, who has brown skin and came from a village in Guatemala, you don't mind opening the door and letting her clean your room. But if she is a sassy African American woman from South Central LA, you’re damned sure not opening your door. Not because you are afraid she'll rob you. It’s because you don’t want to lose face. This is a face to face sociology at work—it’s Erving Goffman—with someone you recognize as in the same social group you’re in. I thought this was a brilliant insight.

[laughing] You know she’s going to say something! “What the hell are you doing, man?!”

Exactly!

“Get some drawers on!”

Right.

A fair amount of the cultural political economic elite in the country has now more or less fully embraced a critique, even a denunciation of some of the mediating institutions and the standpoint moral discourses on which the country was built. You have a profound paragraph in the First Things essay in which you call yourself a man of the West. You say, “Tolstoy's mine, Newton is mine, this whole set of intellectual and moral and religious discourses that made the West are mine.” Given that much of the economic and cultural elite in the country no longer sees that as central to our project as Americans, and that they exert a tremendous influence over the culture, how can they be opposed?

It’s a hard question. I agree that elites have lost confidence. It's not just that they don't any longer embrace and propagate this sense of pride or ownership of the Western civilization that we inhabit. They don’t even recognize what it is and what is unique about it. My God, slavery is a constant of human experience for thousands of years! What's new is emancipation en masse as a result of a movement for human rights. That's a completely new idea in human history before the 18th century. And where does it come from? We could go through the pedigree, and certainly Christianity is going to be part of that. That's 2000 years plus of the evolution of our social and moral thought, but we don't want to embrace the Christian foundations of our civilization.

I didn't say that everybody had to be a Christian. I'm not now propounding a government religion. I’m acknowledging the intellectual history of the West. I don't know where to start with the exegesis on the origin of this divergence. Is it Vietnam? Is it our loss of the belief in the righteousness of the American project in the global context? Did we miss our chance, and should we have taken our revolution and joined it up with the anti-colonial movements? Would people look more kindly upon the heritage that we have? Is that the beginning of it?

Do we look to the 1950s and the 1960s, where you get this triple whammy of feminism and racial liberation and anti-colonialism all coming together in a brew that leaves the enlightened college graduate or intellectual or journalist or teacher in 1970 looking askance at the project, as opposed to saying, as they might have said in 1945, something much more affirmative? “Hey hey ho ho Western civics got to go!”—Jesse Jackson was leading that chant on the Stanford campus. The athletes at the ‘68 Olympics who did the black power salute—they’re heroes now. No one would ever say of them, “How ungrateful.”

I am a man of the West. What else would I be? I'm not just talking about my mother tongue being English. I'm saying I inhabit the civilization. What else would I be? I'm a person without a country if I eschew that.

Everything else is made up. Kwanzaa, with great respect, is a poor substitute for Christmas. And not because Jesus is Lord, but because you made Kwanzaa up yesterday in a vain attempt to bridge a chasm that will never be bridged, a chasm that was created by the Middle Passage. This is a windmill tilt, the idea that you can reinvent. You can't. Your heritage is in the spirituals. It’s in the slave quarters of the 1840s and 1850s in Mississippi and Alabama and North Carolina where, as many cultural historians will tell you, the root of the black church was forged. That's your heritage.

We’re so rich, we’re so powerful. They say white supremacy and white America stole the land from the Native Americans. Certainly the native population was decimated and was dispossessed. I don't dispute that. I would observe though that this is the story of the development of human civilizations going way, way back. That's not a new thing. I grant that it happened. Hindsight is 20/20. It’s retrospective morality when we use the experience of the last 200 years that has created the world that we now live in and project our values back onto people 200 years ago, and then judge them based on their race.

We stand on the result of all of that historical development. African Americans are rich and powerful, we have a long life expectancy, and our children can dream of anything. What are you talking about that we're not people of the West, and we’re Africans? That’s infantile, in my opinion. Eugene Genovese, in Roll, Jordan, Roll, and Sterling Stuckey, in Slave Culture, show that it’s all about what happened in 1820 and 1830 and 1840, as best they can figure out. That’s where the story begins for African Americans.

The thought that came to my mind as you were talking about that heritage was of an experience I had the first time I was out of country for an extended period of time. One of the moments in my life in which my Americanness most profoundly showed itself to me at an emotional level. I went to France as a grad student to do archival research. And I spoke French very imperfectly at the time. Linguistic difference always immediately makes you understand that you're not in the in group. I’d been there for just a few weeks. I felt very depressed that my language skills were so bad and that I was faring so terribly in other ways as well. On French television, I happened on a program about American jazz, and turned it on just during a bit on John Coltrane. It was not just hearing him play. They had some interview footage, and when Coltrane spoke, I heard my language, American English, coupled with that musical tradition that I loved.

Yeah.

It immediately just flooded through me: “There are my people!”

[laughing] Yeah.

“Those are my people, and they're still there, and I can go back across the ocean, and I can find them again after this harrowing experience that I've had here across the sea.” Across the sea in a place, by the way, surrounded by a bunch of people who looked like me but were of another group. And looking at an image of a guy who looked quite different than me, but whom I immediately recognized as a member of my group.

Good story.

This has been wonderful. Thank you, Glenn.

Nice to talk to you.

Dr. Loury, your description of the creation of the George Floyd narrative is something everyone else seems afraid to address. (And I very much include the Taibbis and Greenwalds of the world.)

As you are undoubtedly aware, the creation of another narrative is right now being attempted in Grand Rapids, Michigan. From the refusal of the state to release driving records (an action which had to be reversed) to the fishiness surrounding criminal records (I'm not sure what the reality is, but Andy Ngo is providing a case number for an assault on a pregnant woman; other sources are saying nothing at all).

As you pointed out, the media and politicians have the agency to create a narrative. Right now their cards are face up on the table for all to see in Grand Rapids.

In addition to those two matters I just mentioned, the New York Times has written:

"The police in Grand Rapids, Mich., released videos on Wednesday showing a white officer fatally shooting Patrick Lyoya, a 26-year-old Black man, after a struggle during a traffic stop last week."

Contrast to their withholding the race of the Black mass shooter on the NYC subway last week. Because, race doesn't matter when a mass shooter is loose amongst the public, I suppose.

Agency, indeed.

I have a dilemma concerning religion. While religion may provide some solid moral examples - along with their opposite - it is superstition. So many of the beliefs are ludicrous to me, that going along with "religion is a good" seems incredibly condescending.