It’s gratifying whenever anyone asks to interview me, no matter who they are. But there’s something special about publications outside the US seeking me out for commentary. Recently I talked with Sascha Chaimowicz for Germany’s Die Zeit. Reading about the ethnic and racial politics of other regions can be a surreal experience, since the particular histories of particular nations lead to controversies, discourses, and patterns that sometimes resemble a funhouse mirror version of our own. I wonder if German readers who take an interest in this interview will find analogs in their own society or if they’ll simply marvel at our (or my) strange way of talking about race. And if you happen to be a German reader who’s found your way here, let me know in the comments!

We conducted the interview in English, of course, but if you’ve got sufficient German under your belt, you can read the translation here. Below I’m presenting the conversation in the English original. I talk a bit about the election here, but tomorrow you can tune in to hear John McWhorter and me discuss it more fully. And I don’t mean only paying subscribers. Normally, we release new episodes to paying subscribers on Mondays and to the general public on Fridays. But because this is a particularly time-sensitive episode, we’ll be releasing it to everyone on the same day. So if you listen and find you like starting your week with The Glenn Show, consider becoming a paying subscriber.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

Mr. Loury, Barack Obama complained a few days ago about black men not supporting Kamala Harris, he said, “Part of me thinks you just don't want a woman president and come up with other reasons.” What was your first thought when you heard that?

Here's a man who lives in a world of mansions, $500,000 speaking fees, and Netflix deals, floating down to us and lecturing black men on how to vote. I couldn't believe how arrogant that was.

But in fact, the polls show that support among black men for Harris is weaker than for previous Democratic candidates. Does that surprise you?

Look at the conditions in the inner cities where many poorer black people live, in Detroit, St. Louis, Baltimore, Chicago: because of inflation, people can no longer afford housing, medicine, care for their grandparents. Schools are so bad that pupils no longer learn to read and write properly. There is constant discussion about police violence, but in everyday life, crime among black people is the much bigger problem, the murders, the car thefts, the robberies, the rapes. Besides, Kamala Harris is simply a weak candidate. She's not convincing, she's not charismatic, she's not visionary, she's not eloquent, she's not Barack Obama. In light of this, I think the 78% approval rating among black voters is actually quite high.

Why are black men in particular turning away from Harris?

The demographic statistics show us that they are worse off: they are overrepresented in prisons, they are less educated than women, their health life expectancy is lower. And it may be that there is now a kind of male resentment, a feeling that women get more attention from Democrats. Just think of the term toxic masculinity, which is popular among Democrats. If you value making certain jokes, flirting, moving with a certain swagger, you might already get the impression that you're no longer wanted by Democrats. Perhaps we are dealing with a feminization of the center-left.

Surveys show that almost 30 percent of black men under the age of 45 want to vote for Trump, a man who many consider to be a racist. Does that surprise you?

Let's get specific. For example, a few years ago Trump referred to countries like Haiti as “shithole countries.” Many white, liberal Americans immediately accused him of racism. Have you ever been to Haiti? Nothing against the country, but you can objectively state that the country doesn't work, also for historical reasons. My impression is that the skepticism of many black people in such moments is directed more towards those who cry racism in order to draw voters into their own camp: They sense that they are being manipulated.

When you say that accusations of racism are often used strategically, what about, for example, Trump's conspiracy theory that Obama might not even be an American? Did racism not play a role there?

That was shabby gutter politics. But I always found the warnings about Trump being a racist and a fascist hysterical. They're a distraction: In a TV interview with JD Vance, half the time it was about whether Trump had exaggerated when he claimed Venezuelan immigrant gangs had taken over the entire town of Aurora, Colorado. Trump had exaggerated, but instead of talking about the real gang problem in Aurora, the interview turned into a referendum on Trump the racist liar. It's moments like this that make me wonder: do they think I'm a fool?

After all the debates and accusations: How do you see Trump today?

I never supported him, even though he amused me at first. I found myself watching his rallies on TV with a beer and thinking, “This is going to drive the culture barons at the Washington Post, the New York Times and the New Yorker, who were always on my back, crazy.”

As a black conservative, what is your political identity based on?

I am a free-market liberal economist, I have great respect for religion, and when it comes to the plight of African Americans, I believe in personal responsibility. Enough with the whining and excuses! I don't want blacks to become supplicants, dependent on the benevolence of white left-wing liberals who will please overlook our weaknesses by, for example, lowering the standards for admission to universities because otherwise too few of us would make it there. Nobody does that for Asians. Nobody does that for the Jews.

You are 76 years old and lived through the civil rights movement and the election of the first black president. How is black America doing today?

On the one hand, it's a story of incredible progress. In my 76 years, black people have risen to the top in pop culture, sports, business and politics. But when it comes to the lower classes, I'm pessimistic. Let's look at families. There are more children born out of wedlock across ethnicities than there used to be, but in African-American societies the rate is particularly high: 70 percent of babies born to black women are out of wedlock. In most cases, this means that the child grows up without a father. In the inner cities of New York, Detroit or Chicago, the rate is 90 percent.

What are the consequences?

Mothers are alone with all the children. The lack of responsible male role models, of educational figures who convey a sense of right and wrong, has consequences. With all the drug dealers, murderers, and thieves, I often wonder whether things could have been different if the fathers had been there for their children. But please don't get me wrong: I have nothing at all against the sexual revolution and modern thinking on freedom, that's the way things are.

Why can the upper classes afford to live this freedom, while it often leads to problems for the lower classes?

Well-educated, economically successful people of all ethnicities tend to stick to traditional family relationships in the end, despite professions of freedom. And if they do decide to take a different path and raise a child alone, for example, they have more stable jobs and a secure environment to help them. The same applies to experimenting with drugs, with the phases of self-discovery that are normal for young people from the upper classes today: You have to be able to afford it.

You grew up on the South Side of Chicago in 1948, an area that today has become the epitome of a black problem neighborhood. What was your childhood like there?

Very different to how it would be today. I grew up in my aunt's house, with six rooms, a garden and fruit trees outside the door. You never heard gunshots. There were well-stocked grocery stores and not a liquor store on every corner. I didn't see any drug paraphernalia lying around. If I left my bike outside at night, it was still there in the morning.

What did the people look like?

They took great care of their appearance: no matter how much crap you had to put up with in the workplace, how many racist insults you had to endure—there was respect among each other, your own reputation was important. We didn't look up to hip-hop moguls with gold chains, but to Duke Ellington with his tuxedo and meticulously groomed mustache. Fifteen minutes away, however, you could already experience what characterizes the entire area today: Men loitering with alcohol in brown paper bags, prostitutes on the street corners.

What values were important in your childhood?

My parents divorced early, my mother was a rolling stone, as they say, and my father was the disciplinarian. My mother, my sister, and I lived with Aunt Eloise, she was an important figure in the family: she always talked about the line that separates right from wrong and that you were never allowed to cross. On the right side, you dressed well, were decent and hardworking. On the other side, the abyss lurked. The reality was different. My aunt sat in the front row of church with her friends, dressed in big hats and furs. But at the same time, we always had an uncle, a cousin, or a brother who dealt in stolen goods and sold drugs. Everything merged, as it did for me later.

At 33, you became the first black economics professor at Harvard. That was your life on the good, decent side.

Yes, I was a successful economist—and a black one, that was important to me. I wrote my dissertation on the economic impact of past experiences of discrimination on young black people. But I always had an interest and affinity for the naughty on the other side of the border. I was constantly cheating, sleeping with prostitutes, smoking weed.

Do you have an explanation for what exactly drew you into this world?

I grew up like that. My uncle Moonie, for example, was a very respectable man, but he was also a heroin addict when he was young and smoked marijuana all the time; he always called it his asthma medicine in front of us kids. Adlert, my other uncle, was a well-known lawyer in Chicago—and a notorious womanizer.

And you learned from him?

You could say that. When I was sixteen, my uncle Adlert said to me: Listen well, son, try to get as much pussy in your life as you can. Don't be afraid to ask for pussy, do it now, do it tomorrow, do it as much as you can.

That's crass advice to give to a sixteen-year-old. How did you take it at the time?

I wanted to be like him. One of the proudest moments of my life was when he once came to my bachelor pad when I was a young professor. He stood there and said: “This is the ideal seducer's apartment.” A few days later, he visited me again and brought me his silk paisley jacket. He said: “I want you to wear it. You'll be able to use it better than I ever could.”

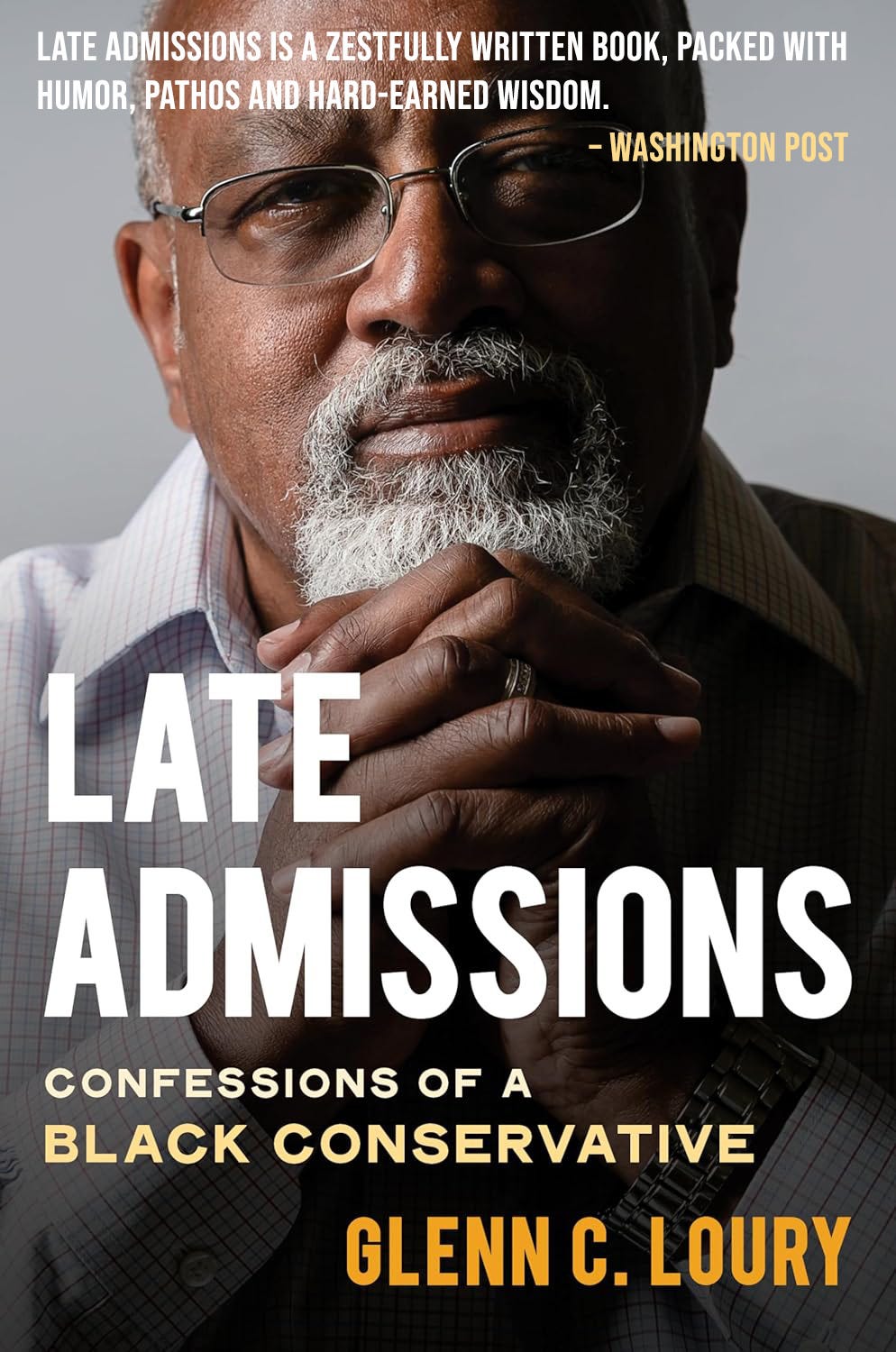

This year, your memoirs were published in the USA, in which you confess: I was not who people thought I was. For example, you tell how it came about that you did not become deputy secretary of education in the Reagan administration, even though you were about to be nominated.

I had an affair with a woman in her early twenties, I was in my late thirties. I was married and housed my affair in an apartment that I rented specifically for her. Shortly before I was nominated, the FBI did a background investigation. They showed up at the rented apartment one day and talked to the young woman. When I found out about it, I knew that was it: I was unacceptable to a conservative administration with this story. And I withdrew from the nomination.

She later accused you of domestic violence, but she dropped the charges.

Yes, that came afterwards: One afternoon I tried to push her out of the apartment through the door with my hands on her shoulders. It was awful and aggressive. I didn't hit her, but you could call it domestic violence.

You became the person you always warned black America about, and still do today: you had illegitimate children you didn't take care of, you notoriously cheated, you took drugs.

Yes, yes. I've done so many things wrong. I remember once sitting with a theologian friend of mine and saying: “Look at Martin Luther King Jr. He wasn't always faithful to his wife either, and we still see him as a moral role model.” The theologian slammed his hand on the table and shouted: “How dare you tell people how they should live and then act so indecently yourself?” I was too self-righteous back then to fully realize what I was doing to my wives, my children, my partners, and my friends.

You even took crack cocaine when you were already a Harvard professor.

I know it's hard to understand. I have a suspicion that it had something to do with my idea of black authenticity, even though I don't want to equate being black with drugs and sex. In my professional life, I was surrounded by white people. But through my nocturnal excesses, I could feel closer to my people for a few hours when I went to the slums, for example. I changed my walk, put on a cap, spoke differently.

How did you come to smoke crack cocaine?

I met a girl in a bar, a sex worker. We ended up in her apartment, she asked: “Do you want to try something?” I did, and it took me a year to get off the stuff. I ended up in a rehabilitation program where, apart from me, there were only homeless people or prison inmates who had been transferred to the facility.

Which confession in your book was particularly difficult for you?

There are a few. That I had an affair with my best friend Woody's wife. Or that I smoked crack in my Harvard office—door closed, towel under the door slot, it was surreal.

What was your motivation for revealing all this in your memoirs?

I wanted to write an honest book, an honest introspection. That was my life.

People often get the impression from you that you are comfortable in the role of the contrarian who likes to provoke. After the death of George Floyd, who was killed by a white police officer during an arrest in Minneapolis, you invited two filmmakers onto your podcast The Glenn Show: The two took the position that the police officer could be innocent because he had only followed protocol. Later research showed that this was nonsense. You apologized publicly. What prompted you to invite them?

That's something I don't like about myself: that sometimes my critical faculties shut down when someone presents me with a piece of evidence that makes me feel good and confirms my worldview. I wanted to believe what the filmmakers claimed. Because I had big problems with the riots after the killing of Floyd, with Black Lives Matter and the heroization of George Floyd.

Why?

It's tragic that Floyd was in the wrong place at the wrong time, but the way he was made into a symbol for black America afterwards was wrong. The George Floyds of this world, standing around high at eleven o'clock in the morning, messing with cops, robbing stores, handling counterfeit money, neglecting their children—they stand for black weakness.

But you weren't that different, were you?

I see you now want to slip into the role of my psychologist and think I'm judging so harshly because I recognize myself in Floyd.

I didn't mean it quite so profoundly. I'm just amazed at how cool you look at George Floyd.

The truth is: I was ashamed that someone like that became an icon of black life. What does it say about us African Americans that a figure like this, of all people, evokes our most intense, emotional reactions?

You also like to clash with your own conservative camp.

In the late nineties, after my Reagan years, I was even considered to be in the progressive camp for a while, arguing against the police and against the mass incarceration of black people. But now I guess I remain a conservative.

You recently defended the new book by the black progressive star author Ta-Nehisi Coates, with whom you are usually at loggerheads, quite passionately: in it, he describes Israel as an apartheid state.

However, I wasn't advocating for Coates's position on Israel, but rather admiring his craft, and also his courage—putting his career on the line to express something that is important to him.

Does it really take courage in American intellectual circles to call Israel an apartheid state? Black publicists in particular are constantly projecting their own history onto the Israelis and the Palestinians by turning the Jews into whites and the Palestinians into blacks?

I understand what you mean—and realize that I won't have an easy time defending my position on Coates in the coming weeks.

Finally, I have to ask you: despite everything, will you vote for Kamala Harris?

No, I will not vote for her, but probably for an independent, non-partisan candidate.

Why would you not vote for Trump?

I didn't think his first presidency was a disaster, not economically, and not in terms of foreign policy either, there were no new wars. But he tried to repeal Obamacare, I don't support that: healthcare is basically a human right, a decent society has to look after its citizens. Trump also had every right after his election defeat to go to court to challenge the result. But he should have acknowledged the court decisions and thus his defeat. A terrible precedent. If someone says I won't vote for Trump for that reason alone, I could well understand that. But even if I were to vote for him, I wouldn't tell you that.

Why wouldn't you do that?

Worried that my reputation would never recover and that the first line of my obituary in the New York Times would read: “Glenn Loury, well-known black economist and Trump supporter.”

Interesting interview.

But let’s get something straight about Geroge Floyd. He wasn’t murdered. The original coroner’s report found nothing concerning the knee on the neck. But the knee on the neck made a great photo op for anti cop bigots, so they played it for all it was worth. The entire case was built around that knee, never mind that it had nothing to do with Floyd’s death from a serious self-inflicted overdose.

Glenn had the courage to link The Fall of Minneapolis on his podcast. It is far closer to the truth than any of the crap the MSM ginned up.

https://www.thefallofminneapolis.com/

Billions of dollars of damage was done in the subsequent riots, which Nancy Pelosi and others called ‘mostly peaceful protests’. By my best count, 25 people were murdered. Innocent people were yanked out of cars and beaten. Mom and Pop stores were destroyed. Electronics and clothing stores were looted in the name of ‘social justice’.

Pelosi is a big fan of mob rule. As long as it’s HER mob.

I worked for the World Bank for 20+ years. Haiti is a s***hole. Why even politicize that? Fact.