Today we’ve got a special post from an old friend of mine, Charles L. Glenn, who was my colleague 30 years ago at Boston University. As you’ll read below, Charles participated in the civil rights struggle in the ‘60s, traveling to the South to protest and organize. Like many of his generation, he put his body on the front line to help secure the rights of black Americans living under Jim Crow. And he has continued to work for social justice throughout his life, especially in the realm of education.

But while Charles’s dedication to social justice has remained constant, his ideas about how best to achieve it have changed. And why shouldn’t they? Anyone who spends a lifetime thinking about and studying a problem will almost certainly change their mind about the best ways to address it. The problem of ensuring equality of educational opportunity under conditions of differing socioeconomic status within a democracy is extraordinarily complex. It would have been shocking if we had found the right solutions in the immediate aftermath of the civil rights movement.

Unfortunately, many progressives are unable or unwilling to acknowledge the failures of the past. Charles’s knowledge and expertise have convinced him that, in order to improve our educational outcomes, we need to adjust our thinking, especially regarding school choice. Ironically, Charles’s ability to make those adjustments has put him out of sync with present-day social justice warriors. But social justice is not reducible to a set of ideologically determined bullet points and programs. It consists of a continuous pursuit of common goals in an ever-changing social and political environment, wherever that might lead.

I’m proud to be able to present an essay from a true social justice warrior here for you today. Let us know what you think!

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

Social Justice Has Changed – I Haven’t

By Charles L. Glenn

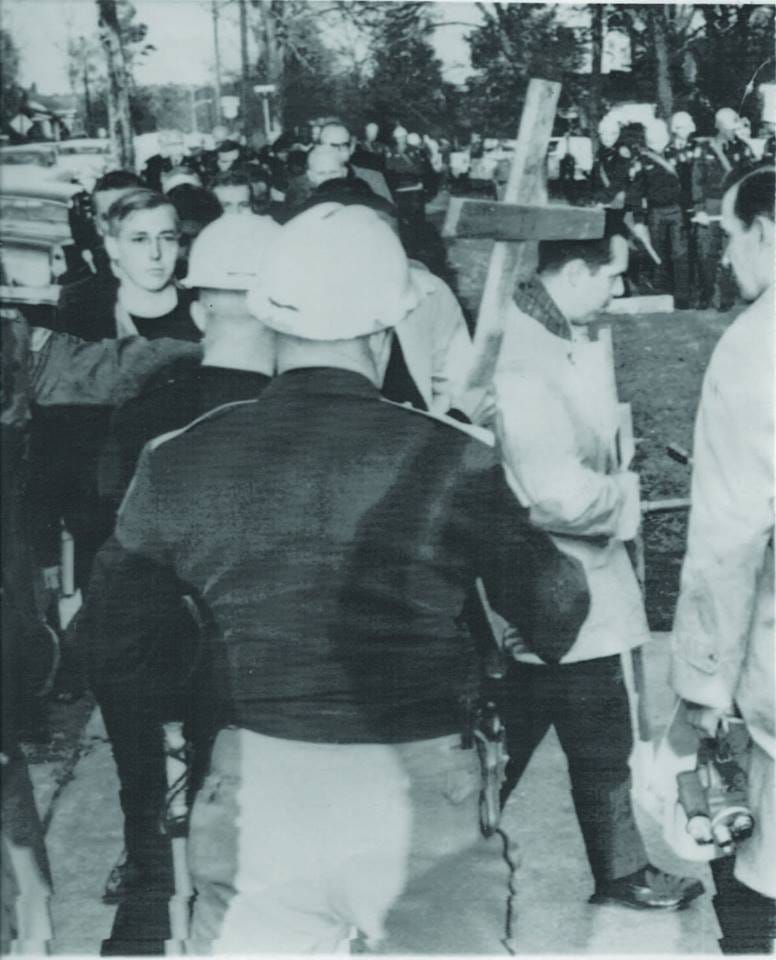

I came of age with the ‘60s and the awakening concern for social justice. By 1963, I was dabbling my feet in the Reflecting Pool while MLK called for an American future beyond race. Several months later, I was in jail in North Carolina as part of what we called the Freedom Movement. In 1965, the New York Times Magazine used a photo of me in Selma to illustrate an article on “the radical clergy.” I was an adherent of what John McWhorter in Woke Racism calls “First Wave Antiracism,” which fought slavery and legal segregation.

By 1970, with a Harvard doctorate in educational policy, I was on the staff of the Massachusetts Department of Education and soon headed a new Bureau of Equal Educational Opportunity. Along with bilingual education, sex equity, and other new agendas, I was responsible for pushing forward the lagging desegregation of public schools in Boston and elsewhere. This I did with such vigor that by 1974 I was widely known and resented as “Mr. Busing,” as school buses rolled to implement a desegregation plan of which I was principal author. Media from around the country and beyond gathered in South Boston to report the rage of white adults at the intrusion of black teenagers into “their” high schools.

The Boston Globe called me “the state’s lightning rod for the stormy protests against the racial imbalance law and the plans for Boston and Springfield schools,” and Anthony Lucas, in Common Ground, described me as having “a passionate zeal on racial issues.”

Now, fifty years later, I’m considered a conservative in education policy circles. I support parental choice in its many forms: charter schools, vouchers, homeschooling, etc. I served as an expert witness in a number of cases challenging the restriction of public funding for faith-based schools. I’m also very critical of much that is done or proposed in the name of racial justice and of the current obsession with racial and other identities.

What happened? Is this an illustration of Robert Frost’s quip, “I never dared to be radical when young for fear it would make me conservative when old”? Have I abandoned my youthful convictions and become complacent about racial and other injustices? Not at all; I believe I am as passionate as ever about these continuing problems, but that I have learned from experience and from my own mistakes to advocate for more effective remedies.

We were right about one big thing in our pursuit of justice in the ‘70s and wrong about another. The irony is that both what I held to then (and hold to still) and what I changed my mind about put me in basic conflict with the current “social justice” orthodoxy.

What I Was Right About

The one big thing we were right about is that racial and social class integration can be a very good thing, both for how and what children learn and for the quality of the education provided to poor children. But there is nothing magic about integration and, done poorly, it makes things worse. We found that two qualities were essential to the success of integration: ample opportunities for students to work together on projects and a climate of mutual respect.

The purpose of creating contexts in which white students worked together with black and other “minority” students (as we then called Hispanic and Asian American students) was to encourage them to focus on the common task or discovery rather than on racial and ethnic differences. Through these shared efforts they came to respect, to trust, and often even to like one another.

That is of course the direct opposite of what McWhorter calls “Third Wave Antiracism,” the new orthodoxy in progressive circles, which “teaches that because racism is baked into the structure of society, whites’ ‘complicity’ in living within it constitutes racism itself, while for black people, grappling with the racism surrounding them is the totality of experience and must condition exquisite sensitivity toward them, including a suspension of standards of achievement and conduct.”

The working-out of this divisive ideology in schools, as has been reported from across the country, involves heightening racial self-consciousness in ways large and small, persuading some children that they are inevitably victims and others that they are inevitably oppressors. The focus is no longer on shared projects but on divisive grievances.

I continue to believe that we were right to encourage students to work together in ways that made their common goals more important than their racial or ethnic differences and even led them to submerge those differences in new friendships.

What I Was Wrong About

But I grew convinced, four decades ago, that we were wrong about another big thing: that parents could be simply left out of consideration, that children were somehow available as an object and instrument of public policy. I came to see, through paying attention to what was going well (voluntarily-chosen magnet schools) and what was going badly (mandatory assignments based on residence), that a successful pursuit of justice should not sacrifice freedom, but should seek to bring these rights into partnership.

This came home to me in the middle of our battles over desegregation, when I wrote in my journal “Fiat justitia ruat cælum” (“Do justice though the heavens fall”), and then asked myself, if the heavens fall, if the whole system collapses, what good will justice be among the ruins? And I began to look for ways to achieve our goals of increased opportunities for minority students and immigrant students and students from marginal families that would at the same time empower those families rather than simply extend the reach of government. My years as an inner-city pastor had convinced me that poor parents were deeply concerned about their children. But they often felt helpless to make decisions affecting their future. Choosing among schools was a way to build their sense of agency and trust.

This led me to become a strong advocate of parental choice of schools and of opportunities for educators to create distinctive schools so that those choices would be meaningful. At first this just involved choices among schools in a school district–and by 1991, when I left government to teach at Boston University, there were 18 Massachusetts cities with school choice in operation. But I also became an early supporter of the idea of public charter schools independent of any school system.

While still serving as a state official, I had begun working on a second doctorate, this time under the supervision of the sociologist Peter Berger. My dissertation would become my first book, The Myth of the Common School (1988). This historical study of the French, Dutch, and American approaches to the role of the state in popular schooling led me to a more consistently pluralistic position. After decades of conflict over the religious content of schooling, the Dutch had decided to provide equal public funding to all schools, whether operated by the government or not. As a result there were several dozen alternative models of education and little of the conflict over schooling that is so common and harmful in the United States.

Thus I came to support vouchers, tuition tax credits, education savings accounts, and other means of providing public support to allow families of modest means to make fundamental choices about the education of their children. And I went on to support homeschooling as well.

I have not become a libertarian. As I tell my friends at the Cato Institute, I’m a Calvinist. I believe in human sinfulness, and therefore I’m convinced of the necessity of a continuing government role to ensure that every child receives adequate instruction. But this government role should focus on measurable outcomes in a limited range of instructional areas. It should by no means seek to regulate how those outcomes are achieved, nor should it extend its oversight to the whole content of the education provided by schools.

A Belgian colleague and I have edited three editions of Balancing Freedom, Autonomy, and Accountability in Education, a four-volume survey of more than sixty national education systems, which is now available free. In each case we ask the authors to explain to what extent parents have the freedom to choose among schools and to what extent educators can create distinctive and focused schools (within a context of public accountability) for satisfactory instructional outcomes.

The irony is that this focus on empowering parents—especially those with modest resources—to make decisions about the education of their children, within appropriate safeguards, has come to be seen in “enlightened” circles as regressive. There are many calling for “social justice” who believe it essential for the state to promote the autonomy of children by radically limiting the influence of their families and communities.

Those—like me—who argued half a century ago that justice required the state to interpose its authority between parents and their children were wrong. Those who promote such policies and practices are still wrong today. I think I have learned from both the failures and the successes of the last 50 years. I find it very sad to see the enthusiasm with which those achievements are being abandoned and the failures embraced.

I remember Charlie Glenn from afar back in the day. I lived on Schiller Street in Jamaica Plain, one block from the Bromley-Heath Housing Development. Our kids had been attending the Hennigan Community School for about four years. Many of us in the neighborhood first became aware of Bussing, when we heard that many of the kids in our school were going to be bussed elsewhere, while other kids were going to be bussed in from other parts of Boston. It was ironic. The Hennigan -- if I remember correctly -- was about 85 % minority (most African-American) -- and there was a lot of energy put into gaining community control over this newly built school (which we and other white parents had fully participated in), with a lot of community facilities in it. But here, a sizable portion of the Black students were being bussed out, while mostly white students were being bussed in.

There was general outrage at a community meeting at the Hennigan School chaired by either Milt Cole or Bill Gaines (from the Bromley-Heath Tenants Association). No one wanted it. We agreed to meet in a week when we figured out what was going on. At the next meeting Milt and/or Bill told us: "We've got a problem! This plan is baked into the desegregation decision. If we don't support it, we will end up supporting continued segregation in the Boston Schools. It's not a good plan, but we have to go ahead with it. In the best of circumstances it is is going to be five really difficult years, which we have to be prepared for." I was president at the time of the Hennigan Home and School Association (PTA) and suggested that we might try to improve the plan; play with the numbers and see if we could reduce the number of kids bussed.

We then convened another meeting at the Hennigan that I will never forget. There must have been close to a hundred people there from the neighborhood. It was surreal, but in a good way. We did simultaneous translation into Spanish and English. Some who spoke both languages -- or thought they did -- translating what people were saying to the group as a whole into the other language. As a group we committed ourselves in the meeting to come up with an alternate plan that bussed as few people as possible, and bussed those people to better schools. As it stood, the bussing plan called for bussing 20% our kids somewhere else. We reduced it to 8% and everyone who was bussed was bussed to a better school in Jamaica Plain, and maybe a little beyond. We had a blackboard to record our calculations, which were actually done by one of the fathers who was a mathematician, and very adept at, believe it or not, with an abacus. We then voted on the plan and everybody supported it unanimously.

We sent it on to Charlie's office, where it was summarily dismissed because it either made things worse with their system-wide calculations, or just would have been too hard to integrate with their earlier planning. I don't know if any of our number became anti-bussers. I doubt it. Milt or Bill had made the case against opposition to bussing too well and too convincingly. But there was no one among the people we knew in our neighborhood circles who had any faith in the State Board of Education after that, or trust that they would do right by our children.

I should add that when we talked about choosing better schools, we had no clear idea of what that might mean, apart from good teachers, safe classrooms, and kids learning a lot. So, our focus was on physical infrastructure mostly, on the (probably mistaken) assumption that they would clearly invest more effort and resources in newer schools. In our modest little neighborhood plan we bussed kids to one of the two new community schools: the Henningan, and perhaps (if I remember correctly) the Ohrenberger in nearly West Roxbury.

One of the things that the State (and its various minions) said during this process is that they were going to involve all of the universities in improving the Boston Public Schools as part of the desegregation decision. At the Henningan, as it turned out, this meant that Lesley College showed up and was going to help our teachers orient the curriculum around Multi-Cultural Education. That was what was going to make us special. I remember asking, as the President of the Hennigan Home and School Association, why this was different. I thought more cultural sensitivity was supposed to be a goal for the whole system. Their response was a lot of educationbabble double talk. At the time I was teaching at Emmanuel College and found out that our college was at the Ohrenberger and was going to orient the curriculum around behavior modification. It turned out that it was the Psychology Department at Emmanuel that was spearheading the effort and chose this orientation because this was what they specialized in. A glance around at other University-school partnerships seem to reflect the same pattern: what a school got was what a University was willing to offer (and benefit by) in the partnership. My sense was what the State initiatives mostly contributed to in the end was the Balkanization of the system, and the fragmentation of whatever educational coherence it might have had. If there were good principals (like Kim Marshall at the King, where one of my sons went for the 5th and 6th grade,) then the school worked well. Many other places weren't so hot.

A decade or so later, I was appointed to the Board of Trustees of Roxbury Community College where I served for 11 years. Most of the students enrolled at RCC at that time came from the Boston Public School System. We were, and probably still are, an open-admissions college. If you have a diploma or GED, you were automatically admitted. One of the deans at RCC confessed to me that they discovered, when they administered proficiency exams to newly admitted students in order to assign them to an appropriate English or Math course, that close to 95% of them had to be assigned to a remedial course, and the median grade level for reading was somewhere between 4th and 6th. It seemed to me that students like these were clearly unprepared for anything like college work and that many of them probably just wouldn't be able to hack it, in the absence of something like a remedial year where every learning objective built toward integrated skill development or something like that. The dean told me that a faculty committee had in fact met and designed such a program, so long as participating in it was voluntary. When the time came to implement the program only one faculty member signed up for it. God knows why!

I'm not sure what to make of all this, but what was going on in the schools and the surrounding city was troubling, traumatic and at times terrifying. One thing for sure, though, the Social Justice Warriors get very nervous when you tell these stories and really don't want to hear them. Looking back, I think Charlie was a good guy, but we needed a lot more people like Milt Cole and Bill Gaines to get us through what people like Charlie Glenn helped to unleash.

I had the honor to be a Dean at Boston University when Charlie was also a Dean and had many excellent discussions with him. He is incredibly smart and always respectful. Thanks Glenn for posting his essay.