John McWhorter and I are exceptional. We’ve both achieved at the highest levels in our fields, and we’ve done so not because of affirmative action but almost in spite of it. But while our experiences are outside the norm, John and I shared something as young men that is not—or should not be—exceptional. We both knew that, in order to excel, we had to prove ourselves the same way everybody else did. Maybe we were both brilliant, but brilliance is not enough. It’s what you do with your talent that counts. None of our colleagues could look at the sophistication and theoretical rigor of my work or the foot-high stack of John’s articles and deny that we have what it takes, and then some.

The problem, then, is two-fold. On the one hand, African Americans in any field who meet and exceed the standards of that field will have to deal with condescension and undeserved suspicion regarding “how they got here.” That is insulting, and it casts a pall of illegitimacy over their achievements. It compromises how their integrity is perceived, and through no fault of their own. Indeed, affirmative action actually penalizes high-achieving African American, since everyone knows that all black people at the elite level in the US benefit from affirmative action, whether they want it or not.

On the other hand, African Americans who might not be up to snuff but who are nevertheless elevated within their fields may never actually know they’re being condescended to. It’s not as though a hiring committee will tell them, “Well, you’re not the best candidate, but we like your skin color.” These beneficiaries walk around believing their peers regard them as equals, when, in reality, everyone else can see they’re below par. Maybe the hiree will realize what’s happened or maybe he won’t. Either way, he won’t be regarded as a true equal.

It’s obvious why those of us who don’t need special preferences usually don’t want them. It should be equally obvious that the “benefits” less-qualified affirmative action recipients accrue turn out to have downsides. Maybe they’ll have a decent job and a good-looking resumé. Maybe they’ll be associated with a prestigious company or institution. But they’ll pay for it. Not with money, but with their dignity and, perhaps eventually, their self-respect. Is that something any of us can afford?

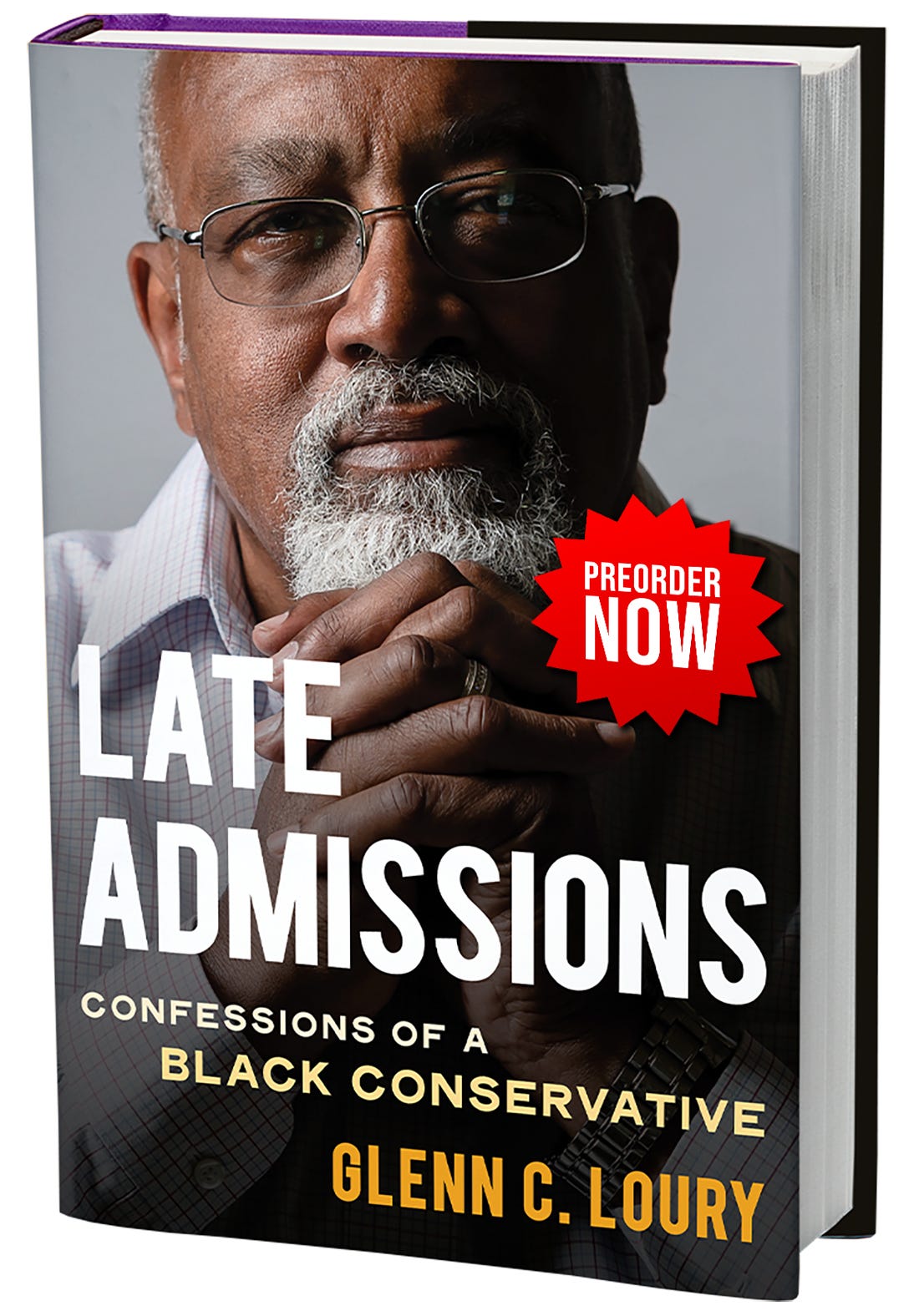

This is a clip from a Substack subscriber-only Q&A session. To view that episode, along with the entire archive, early access to episodes of The Glenn Show, and other benefits, click below.

GLENN LOURY: Okay, John, this is from 0rganiker.

John has mentioned that he benefited from affirmative action as he was coming up, that he secured positions that he was unprepared for but that he realized he currently wasn't up to snuff and boosted his hind quarters to catch up, eventually doing so. John talked about this as a “Sisyphean” task and something that he wouldn't wish upon anyone.

But in fact, there are those who wish exactly that on young black students and expect the same outcome. What's wrong with the path you took, John? Shouldn't it be seen as aspirational that others can follow the same path and benefit from affirmative action in the way you did? Okay, it wasn't very fun to go through the experience of knowing you're not at the level of your peers, but it worked out in the end, didn't it? What would you say to this?

JOHN MCWHORTER: It makes me have to say things that I don't want to say. And it all comes back to the person that we're talking too much about lately.

Claudine Gay.

I'm weird. And I think that's something that maybe this person is missing from that piece that I wrote. And I don't mean that I'm wonderful. I'm peculiar. I am a very nerdy person with a profound love for the printed page who was born with perhaps a very slightly on-the-spectrum insistence on order. And I'm a Montessori kid. For me, the world is my various interests all over the place. That's what life is for me. [John holds up a dinosaur toy.]

Glenn Loury: That's a dinosaur, folks.

John McWhorter: [John holds up a DVD.] These are films discovered in New Zealand from the old days. I like stuff. I'm not trying to show how smart I am. I'm trying to show that I'm weird. And when I found that I was inadequate, I thought, no, I can do what everybody else is doing, and I'm gonna do what everybody else is doing, and I'm gonna give myself the tools to do it, because I wouldn't feel like I deserve to walk the earth if I didn't.

That didn't make me strong. That didn't make me brilliant. It made me weird. I'm glad I did it. And I did bring myself up to snuff. But the problem is that's not what most people would do. Human beings—and I'm not saying black people, but if you're put in that position, that isn't ...

Dammit, I am saying black people! Because of what black people are taught since roughly about 1966. And so, too often in our context, a black person is allowed to not do that, as I would have been too. I got tenure based on a stack of articles a foot high. I could have gotten tenure based on writing two and a half. I know that because I've seen it. A lot. And I don't like to have to say it.

So I'm odd. But the way the culture goes is that the typical black person brought into that position would have wound up getting the same sorts of things that I did without bringing themselves up to snuff. That's the problem with the culture. Somebody might look at me and think of it as inspiring, but no, I'm not the norm. The culture doesn't encourage there to be mes.

If you're black, there are people who are committed to you being in that shop window because of your color, and you are allowed not to do what everybody else does. That's the problem in the culture. And therefore, honestly, I cannot wind back time. I'm not that goodly. I don't know if I would, even if I could. I shouldn't have been put forward so quickly, because I hadn't done anything to deserve it yet.

That's candid. And I respect it. I'm not going to disagree with it, because I can't. That's your report about your experience. My experience was different, though, and I think it has led to me having a different position on the question that 0rganiker is raising. I'm sorry about how this is going to sound.

I was a brilliant kid from the age of 8, 9, 10 years old. I was doing slide rules. I was doing logarithms, tables, and stuff like that. I was doing solid geometry when I was in 7th, 8th grade. I was always a super-smart kid, a little bit like the Matt Damon character in Good Will Hunting. I was a working class kid. I didn't have a lot of polish, but I had real sharp smarts.

My life took a various turn. I was a father at 18 and at 19 and at 21, and dropped out of college. I bounced around community college, got discovered—like Matt Damon in the movie—ended up at Northwestern University where I was a wizard. I got all As in everything: math and economics and philosophy and German. And I was taking graduate-level courses in mathematics and in economics when I was an undergraduate at the college. I was taking the PhD level courses in these technical subjects and acing them. I went to MIT, where I was at the top of my class again.

Forgive this, but I want you to try to understand the point. My genius—yes, I said it—my gift, my extraordinary abilities were what carried me forward, notwithstanding the vicissitudes of racism and discrimination in America. To have that minimized by somebody presuming that, “Oh, you didn't get to MIT without affirmative action” ... and it's actually true. I didn't get to MIT without affirmative action, because every black person is going to be the beneficiary of affirmative action whether they ask for it, need it, or not.

I had a fellowship. Pretty much everybody in the first year PhD class at MIT had a fellowship of one kind or another. Mine came from the Ford Foundation Doctoral Program for Minority Students in Economics. So it was an affirmative action fellowship. MIT had three positions set aside in its entering class. They usually would have 25, but for a few years they had 28. And those three were to be black students of the greatest promise. I was one of them in the year that I came in, even though I didn't need to be in that box in order to get in because I had As in everything. In the PhD level courses I was taking at Northwestern, my professors were writing letters saying that I was the best student they'd ever seen. Because I was.

Again, I ask for your forbearance as I toot my own horn here. Goddammit, don't dishonor my amazing achievement by chalking it up to favoritism! I resent it. I don't like it. I don't need it. I don't want it. That's not a political position. I'm defending my own dignity here. So you gonna call me a sellout because I'm defending my dignity? Fuck you! That's my position

Glenn, they're gonna use that.

It was not a performance. It was honest. Please, will you get your hands off of my dignity? Let me succeed or fail based upon my abilities. Don't patronize me, goddamnit!

In the wake of that piece that I wrote about my own experiences, a lot of very well-intentioned white people told me that I was selling myself short and that I was just describing the same imposter syndrome that many people have when they're put into certain positions. I didn't push it, because you choose your battles. But these people didn't realize how extremely bending-over-backwards these organizations and faculty boards can be when hiring a black person. They really didn't understand that I wasn't talking about just being a little untested, that I was really green. I didn't belong yet.

And elsewhere, we've had a discussion as to whether or not the Claudine Gay issue has moved any needles or been revelatory. In a way, all of what we've learned about that shows what the reality is to an extent. That it's such that she has transparently gotten things that her white equivalent would never even be considered for, because she's black. She can basically just show up—which is what her record is—and wind up climbing the ladder of Harvard and becoming its president. That's what I was writing about. Not somebody just having imposter syndrome because they're 27 and they can't quite believe that they're in the Halls of Ivy.

That's what's done to us as black people. And it is condescending. It does make me want to say “dammit” and “fuck you” sometimes. So I just wanted to add that.

All right, John. Appreciate it. We're going to move on to the next question. And to those who may have been offended by my spicy language, I apologize. I really do.

I was the first woman engineer almost everywhere I went in the 1970’s. I didn’t feel discrimination in undergrad or grad school but in industry I was told about how women didn’t belong at work, about all the stupid women they knew, how men wouldn’t want to work for me and how I ruined the collegial atmosphere. Surprisingly some of these men came back later and told me they were wrong about me and they thought I did a great job. The problem with affirmative action is that it results in people thinking they deserve the grades they get, the schools they get it and the jobs they get. When they finally get told they are not cutting it they are shocked. Companies in one city where I worked put together a program to mentor minorities in Engineering. I was assigned a student (who actually came from a more affluent background than I did) who didn’t show up on time, wasn’t able to work independently, and had very poor communication skills. At the end of the summer there was a big banquet where “scholarships” were given out. Students with C averages were getting full scholarships for the next year. In high school I was a National Merit Finalist and I didn’t get a fraction of the money these students.got. So now they expect the same treatment the rest of their careers. That is why they need safe spaces. People that are qualified don’t need safe spaces. They just want the opportunity to do what they were created to do. I was repeatedly discriminated against because I was a woman. Did I complain - no I just worked harder.

"Please, will you get your hands off of my dignity? Let me succeed or fail based upon my abilities. Don't patronize me, goddamnit!"

Now THAT says it all right there.