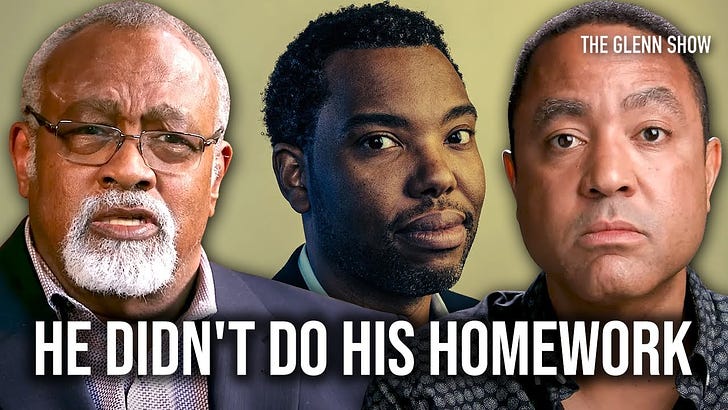

This week’s conversation with John McWhorter features our debate about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s new book. In it, I explain that I admire it for a few reasons, one of which is the quality of the writing. I don’t simply mean that Coates writes sentences that sound nice, though he does. I mean that, in this book, I see a writer mustering his craft in service of deep self-exploration. One could say that the book has four topics: the art of writing, book banning, the African origins of black people in America, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. But its overriding concern, in my view, is how our circumstances—the people who nurture and teach us, the professional environments within which we develop, the culture that shapes us—condition our moral impulses, our sympathetic imagination, and our comprehension of human suffering.

I was interested in similar questions as a young economist. My notion of social capital, after all, was an attempt to describe how the social networks into which human beings are born impart to them certain benefits and extract certain costs that will be realized later in life. We’re all shaped by these networks, and often we inherit from them not only market value as sites of economic production but beliefs, perspectives, ways of thinking, and sensibilities that we carry with us throughout our lives. Examining those values—our own—is not something that can be done with an equation. Most of us engage in that analysis only incompletely, if at all.

In this clip from our conversation, John says that if we seek to understand how young men can be convinced to commit an atrocity like the October 7 massacres, it is not enough to imagine what it might be like to grow up as they did. One must “stand outside” of that perspective in order to place it within its context. That’s probably true. But the “outside” John refers to is also a position. And if our analysis of the situation “on the ground” has no account of the position from which it’s viewed—of the perspectives and sensibilities that shape it—clarity will escape us.

I’m certainly not saying I possess such clarity. Perhaps neither I nor John nor Ta-Nehisi Coates are the right guys to provide it. I say only that it’s needed, and that it’s hard to find.

This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

JOHN MCWHORTER: If you know his previous work, he doesn't have to use those words. Isn't that true? It's all about whitey. It's all about white supremacy. That's why he cares so much about this situation as opposed to what's going on.

GLENN LOURY: That's not what I got from reading this book. What I got from reading this book is all about our humanity and about the various snares, delusions, and temptations that could cause us to disregard it and about the heinous crimes that we can commit—we human beings can commit—even in the wake of our own heinous victimization.

It's about trying to give voice to lives otherwise invisible. And that's, in this instance, the Palestinian voices. It's not just about Israel, it's also about the United States of America. It's about us. It's about our entailment in the tragic unfolding of events there and about how we—that is, all of us—talk about it. Which brings me to the subject of your column and your reprise ...

Glenn, just a second. I wasn't aware that we needed to be treated to the humanity of people living in Gaza. If you're somebody who opens up your phone, isn't it rather clear that to be someone who lives there now is an aching tragedy? All of these innocent people whose lives are being utterly ruined and often who are losing limbs and lives because of something much larger than them—is that a lesson that we really need him to teach us? Who's unaware of their humanity?

There are times when I hate words these days. The use of that word [“humanity”], he uses it a lot.

I think if you listen to the way that the issues here are discussed in the United States and the mainstream media and the corporate media and the respectable press. Not in the independent media. Not if you go to certain websites. Not if you follow Jeffrey Sachs, a Jewish economist who teaches at Columbia, your colleague. Not if you follow John Mearsheimer, a distinguished political scientist at the University of Chicago. Not if you follow Larry Wilkerson, the former chief of staff to Colin Powell, the secretary of state of the United States, and so on. Not if you follow Glenn Greenwald, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who's an independent broadcaster and talks critically about these issues. Not if you follow judge Andrew Napolitano, relatively conservative, a military and foreign affairs type guy, who has a lot of the people who I've just mentioned and others on this program.

When they talk about these issues, you hear it talked about in a different register, you hear a different critical edge, and you hear the constant presence of the humanity of the Palestinians not being lost track of. I don't think you hear that in the mainstream media. I don't think you hear that at the Atlantic. I don't think you see it at the New Republic. I don't think you see it in the New York Times. Yes, there are things to be said on behalf of the humanity of the Palestinians which are not said in the American political discourse and can't be said because we're killing them by the boatload.

We are killing them. We are complicit in the prosecution of the complete obliteration—we're talking tens of thousands. We don't know how many are dead. The babies, the innocents, the fires, the collapsed buildings, the collateral damage, the ratios. No, the discourse here in the United States is not what it might be. It's not as, in some sense, robust and multifaceted as the discourse in the Israeli press. I read Haaretz, and I hear and see analyses, questions, criticisms, and speculations that are more provocative, more penetrating, more balanced than what I read in the American press, again, in the mainstream press.

So Coates's intervention here is important. It's valuable. One doesn't have to agree with it. It's necessary. He's a black intellectual who has a calling. He has a gift and he has a calling. He has artistry, which you've backhandedly acknowledged. And he has a commitment to a certain sense of understanding about the flow of history, the web of culture, where he fits into it.

He's not perfect. And I understand that. I would be the first to call him out for his Afrocentricity and his race obsession and whatnot, and I have done so. But this book—and again, I emphasize, it's not just a book about Israel-Palestine. It's a book about writing. It's a book about craft. It's a book about, as I say, a calling.

Who is he? There's a line in the recent novel by Percival Everett, James, which is a retelling of the Huckleberry Finn story through the eyes of Nigger Jim, the slave: James. He is proudly “James” in the book. And there's a line in there that touches me deeply. It reminds me of Ta-Nehisi Coates. I think this is a quote. He has a pencil. He comes by a pencil through skullduggery, but he comes by a pencil and a piece of paper that he can write on: “With my pencil, I wrote my being into existence. I wrote myself to here.”

That's how Everett the writer characterizes James's empowerment, by his discovery of this pencil and his ability to express himself in words and his ability to write and through the writing to be. This is Ta-Nehisi Coates, an African American of relatively racially radical persuasion, who is a gifted writer at the top of his form, speaking to his reaction to his experience of the dark side of domination, occupation, and conquest. Ta-Nehisi Coates. With his pencil, he's writing himself into existence.

What are we doing besides carping? And I don't mean that personally. I mean it reflexively. Is that my role? Is my role to tear it up on demand, on cue, to rise up and negate the obstreperous, outrageous, undisciplined, ignorant, racist Ta-Nehisi Coates? Is that it? With my pencil, I wrote Ta-Nehisi Coates out of the picture?

I don't know about you, but that is not good enough for me, not in the face of the brilliance of the writing in this book. And again, I stress, it's not just a book about Palestine. It's a book about writing.

That writing, with a capital W, should include genuinely constructive engagement with the situation, which has both a present and a past and, via elision, the word Hamas never appearing, so many other things never mentioned via using the word “apartheid.” Implying that the analogy is penning up Bantu-speaking people in South Africa out of a feeling that they belong elsewhere because they're inferior, as opposed to all of the checkpoints being there because the leaders of the Palestinians in question have vowed in clear language that they wish to erase the country off of the map.

To write with a capital W, and to mention none of this implies—and I get where he's coming from—a little bit of Fanon. I wonder if Ta-Nehisi Coates has read Fanon. What he means is that anything that Palestinians did or do—their leaders, let's put it that way. So that's an important distinction. Anything that those people do, anything Hamas does is justified because white people have their feet on the necks of these people who they came and conquested ..

Wait a minute, he didn't say that, John.

But he means it. The white people came and conquested them.

Have you listened to the interviews?

I have, and that is what he means.

He says exactly the opposite of that in those interviews.

What does he say? I didn't hear him say the opposite. He thinks the white people came in and conquested them. And they've got their foot on their necks, and what happens, what facial expression do you expect when they look up at you, when you take your foot off their necks?

He's read his Fanon, and so he thinks that anything they did, it doesn't even need to be mentioned. It's also convenient not to mention it, but you don't even need to make any arguments about it, because they're justified, because they were conquested by the white man. That's just too simple.

I urge our listeners to read this book for themselves, because I think John mischaracterizes what Ta-Nehisi Coates says.

Tell me why, really.

Let me talk about the post interviews, the ones that I've seen with Ezra Klein and with Peter Beinart, for example, with Trevor Noah and others. He invokes the Nat Turner historical example. This was the slave revolt. You rise up and kill all the white people. And he says, could slavery justify doing that? He says, in effect, were he there, would he be okay with that? It's a question. It's not a statement. It's a question. He realizes that the oppressed may resort to the heinous, anti-human, animalistic reactions to their oppression.

This is true.

There's not an endorsement. It's not saying it's okay, it's good.

With Klein, he did say outright that he can imagine that if he had been a person in Gaza under these conditions, that he can imagine having participated in October 7th. He didn't say it was good.

You can't?

He can put himself in those minds. That is an important exercise.

And I'm asking you, you can't?

Oh, I can very much imagine that state of mind. But if I'm calling myself a public intellectual, I'm going to stand outside and have more to say than just that.

He does have more to say than just that. I'm only trying to acknowledge that he's aware of the possibility that the subaltern can lapse, the oppressed, the dominated, the dispossessed the victimized, the ones who have been plundered can be tempted by seeking a revenge which is imaginable, but which is not something that you could defend. It is a corruption, a deep and profound corruption. I think that's what he would say. He wouldn't say that disregard for human life, such as what was on display en masse in the slaughters of October 7th, is somehow justifiable. He's not saying that.

Again, the interviews are important in my assessment. I don't hear that at all. I hear him saying, “My God, our humanity is susceptible to debasement and corruption of an unspeakable sort, and we're all potentially subject to that loss of moral vision. And the fact of our having been victimized doesn't indemnify us against it or justify it.” That's what I read in this thing.

I don't like the way he's using that word “humanity.” He's done it before. He pulls that out, and it has that ring to it. This is the good writing. I remember he had a debate on Twitter with Jonathan Chait, and some of it was about black intelligence. And the minute he pulled out the word “humanity,” all good thinking people decided that he had won the debate. “If you question my humanity ...” I wish we could go to basic English and only use about 500 words and supremacy and humanity and black body would not be among those words and just say what.

This is really getting me going, and it's really not my issue. I know why it's bothering me. It's bothering me because it's a lazy book. It didn't do the work. Because in the beginning, he dares to say to such a large public that this is not a complex situation, that if you say it's complex, you're just evading the basic morality of this perversion of the way we should treat humanity.

It is complex. And he doesn't want to grapple with it. Yet we're sitting here talking about it, and it's being received as if it was written by somebody who really thought hard about this. Ooh! I mean it, though! It's being received as if somebody did hard thinking. I don't like that.

As an American, a Jew, and a Zionist, I thoroughly disagree with Glenn's assertion that Palestinian voices are being silenced. Everywhere I turn, I see 'free palestine' posters. On every college campus, in constant, repeated protests, in Keffiyehs on the heads of large number of people. I would argue that the voices of the Israeli, tens of thousands, who lost their homes, their families are being silenced by the mainstream media. Further, the number of dead innocent Palestinians that Glenn is quoting are exaggerated figures, provided by Hamas and Qatar. Glenn and John have always taken the position that people have agency, and therefore are responsible for their actions. I can both feel sympathy for the loss of life and property in Gaza, and anger for those who forced this war upon Israel. I can sympathize with the plight of the innocent, who's only crime was being born in the West Bank, while being angry at those who constantly renew the need for checkpoints through their acts of terror. Please Glenn, don't take what you are reading as Gospel. Dig deeper. Use your incredible intellect to see that the tragedy of the Palestinians, in large part, are the fault of the unwillingness to let go of their hate for the Jew. Otherwise we will see more death more destruction, more tragedy. Every people/culture have their flaws. Including mine.

Please stop deflecting the moral blame away from Hamas and those many, many Palestinian supporters, who are to blame for those “innocent lives “ killed in the justified defense of Israel. There is no context that can justify the atrocities that Hamas committed on October 7th (just like all the immoral acts throughout modern history: the Ottoman’s Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, Pearl Harbor, Stalin’s forced famine in the Ukraine, Mao’s Great Leap Forward, and so many more).

Once Hamas and their supporters unconditionally surrendered, then, and only then, should we (or any other interested third party) broker a peace agreement that can endure. Let Japan and West Germany represent the most successful examples of such a peace.