A few weeks ago I posted a compilation of clips on the subject of race and intelligence. The idea that intelligence varies significantly between groups has probably existed for as long as different groups of humans have existed. But the nature of this discourse has shifted over time. The discoveries of evolution, genes, and DNA, along with the emergence of the “intelligence quotient” concept and concomitant advances in the techniques of statistical inference, have brought the methods of modern science to bear on what was formerly the provenance of cultural narrative, myth, and ideology. This shift from cultural to scientific narrative has not made the question of group differences in intelligence any less fraught.

The contemporary controversy around measured differences of group intelligence is so widely known that I need not rehearse it here. And, at least in the US, that controversy entered a new phase 30 years ago, with the publication of Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s book, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. Despite my conservative politics at the time, I didn’t take kindly to the book, as you’ll see in my review of it below, first published in National Review and later collected in both Russell Jacoby and Naomi Glauberman’s The Bell Curve Debate and my own One by One from the Inside Out.

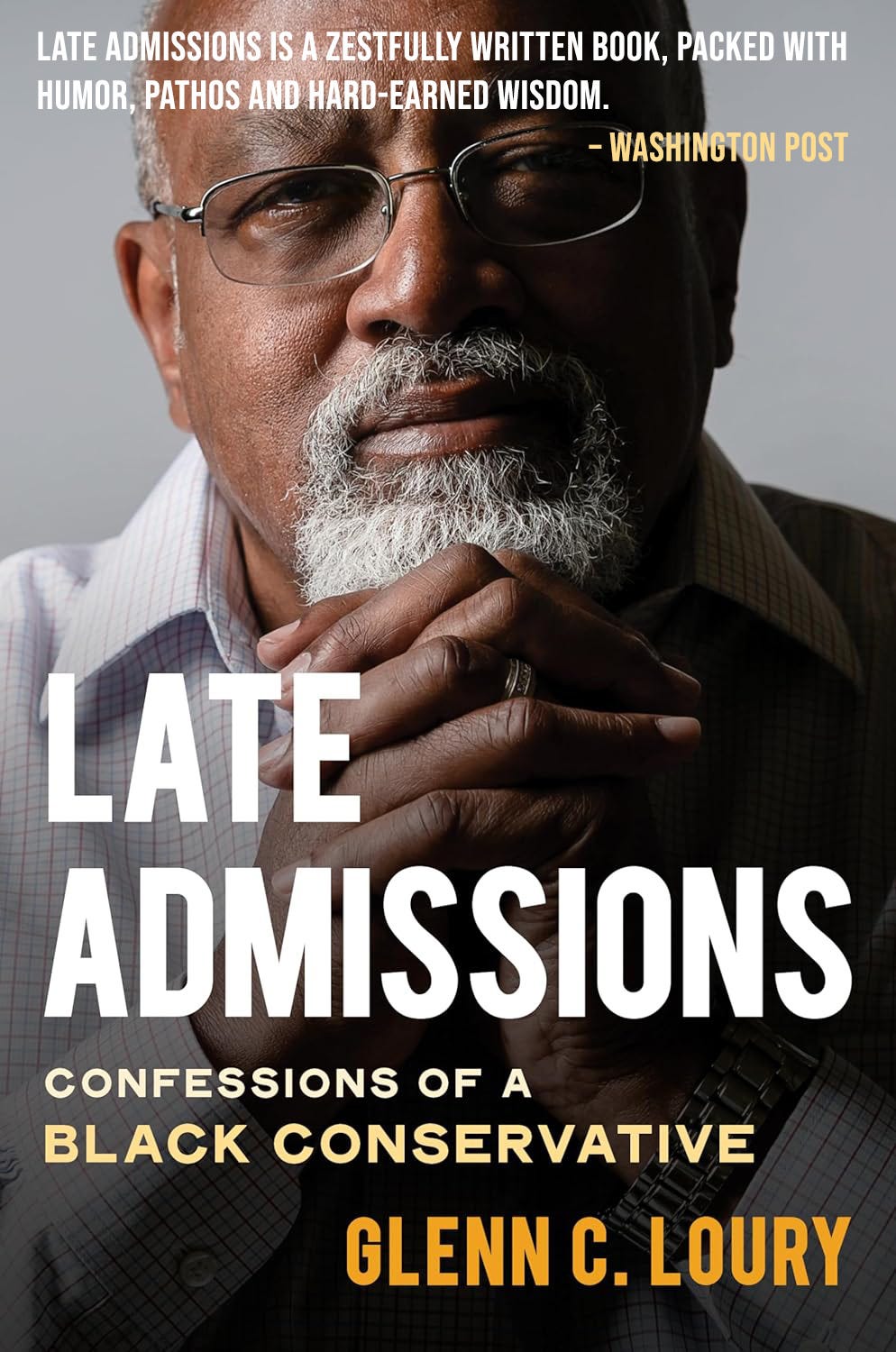

That review was hardly the last thing I had to say about the The Bell Curve. Indeed, as I recount in Late Admissions, I took potshots at Murray in print for years (Herrnstein died just before The Bell Curve was published). I didn’t think Murray was a racist—in fact, we had been friends before I broke with him over his book. But I did think he was giving permission to those on the right who simply wanted to wash their hands of the problem of struggling African American communities, as if to say, “See? We can’t expect any better of them. Their dysfunction is in their genes. So why bother trying?”

I held Murray accountable for that—unfairly so. He was not responsible for misuses of what was, I now believe, a sincere attempt on his part to think through how group disparities in intelligence might influence social organization in the US. And yet I cannot fully disavow my criticisms of The Bell Curve either. I continue to believe there was a serious blind spot in Murray and Herrnstein’s approach. They tended to regard the arrangement of present-day group disparities as a permanent feature of American life. Their conclusions were far too deterministic.

My point here extends far beyond concerns about how we talk about racial differences in IQ. As I’ve argued elsewhere, social science deludes itself when it believes its mechanistic understanding of human subjectivity captures the whole picture. To confidently forecast the future of human development from a series of statistical snapshots is, knowingly or not, to denigrate what makes us human in the first place: our minds, our souls, our free will, our capacity to make and remake our lives as we will. Thinking productively about such things is not solely the province of social science. Treating such matters of the human spirit as mere epiphenomena of material social processes betrays a kind of disciplinary arrogance. It risks opening the door to an unjustified pessimism about the future of human development.

For God isn’t finished with us when he deals us our genetic hand—and you don’t have to be a believer to get my meaning.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

Dispirited

Review of The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life, by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray

National Review, December 5, 1994

Reading Herrnstein and Murray’s treatise causes me once again to reflect on the limited utility in the management of human affairs of that academic endeavor generously termed social science. The authors of The Bell Curve undertake to pronounce upon what is possible for human beings to do while failing to consider that which most makes us human. They begin by seeking the causes of behavior and end by reducing the human subject to a mechanism whose horizon is fixed by some combination of genetic endowment and social law. Yet we, even the “dullest” of us, are so much more than that. Now, as an economist I am a card-carrying member of the social scientists’ cabal; so these doubts now creeping over me have far-reaching personal implications. But entertain them I must, for the stakes in the discussion this book has engendered are too high. The question on the table, central to our nation’s future and, I might add, to the future success of a conservative politics in America, is this: Can we sensibly aspire to a more complete social integration than has yet been achieved of those who now languish at the bottom of American society? A political movement that answers no to this question must fail, and richly deserves to.

Herrnstein and Murray are not entirely direct on this point. They stress, plausibly enough, that we must be realistic in formulating policy, taking due account of the unequal distribution of intellectual aptitudes in the population, recognizing that limitations of mental ability constrain what sorts of policies are likely to make a difference and how much of a difference they can make. But implicit in their argument is the judgment that we shall have to get used to there being a substantial minority of our fellows who, because of their low intelligence, may fail to perform adequately in their roles as workers, parents, and citizens. I think this is quite wrong. Social science ultimately leads the authors astray on the political and moral fundamentals.

For example, in chapters on parenting, crime, and citizenship they document that performance in these areas is correlated in their samples with cognitive ability. Though they stress that IQ is not destiny, they also stress that it is often a more important “cause” of one’s level of personal achievement than factors that liberal social scientists typically invoke, such as family background and economic opportunity. Liberal analysts, they say, offer false hope by suggesting that with improved economic opportunity one can induce underclass youths to live within the law. Some citizens simply lack the wits to manage their affairs so as to avoid criminal violence, be responsive to their children, and exercise the franchise, Herrnstein and Murray argue. If we want our “duller” citizens to obey our laws, we must change the laws(by, e.g., restoring simple rules and certain, severe punishments). Thus: “People of limited intelligence can lead moral lives in a society that is run on the basis of ‘Thou shalt not steal.’ They find it much harder to lead moral lives in a society that is run on the basis of ‘Thou shalt not steal unless there is a really good reason to.’”

There is a case to be made—a conservative case—for simplifying the laws, for making criminals anticipate certain and swift punishment as the consequence of their crimes, and for adhering to traditional notions about right and wrong as exemplified in the commandment “Thou shalt not steal.” Indeed, a case can be made for much of the policy advice given in this book—for limiting affirmative action, for seeking a less centralized and more citizen-friendly administration of government, for halting the encouragement now given to out-of-wedlock childbearing, and so on. But there is no reason that I can see to rest such a case on the presumed mental limitations of a sizable number of citizens. In every instance there are political arguments for these policy prescriptions that are both more compelling and more likely to succeed in the public arena than the generalizations about human capacities that Herrnstein and Murray claim to have established with their data.

Observing a correlation between a noisy measure of parenting skills, say, and some score on an ability test is a far cry from discovering an immutable law of nature. Social scientists are a long way from producing a definitive account of the causes of human performance in educational attainment and economic success, the areas that have been most intensively studied by economists and sociologists over the last half-century. The claim implicitly advanced in this book to have achieved a scientific understanding of the mora/ performance of the citizenry adequate to provide a foundation for social policy is breathtakingly audacious.

I urge Republican politicians and conservative intellectuals to think long and hard before chanting this IQ mantra in public discourses. Herrnstein and Murray frame their policy discussion so as to guarantee that its appeal will be limited to an electoral minority. Try telling the newly energized Christian right that access to morality is contingent on mental ability. Their response is likely to be, “God is not finished with us when he deals us our genetic hand.”

This is surely right. We human beings are spiritual creatures; we have souls; we have free will. We are, of course, constrained in various ways by biological and environmental realities. But we can, with effort, make ourselves morally fit members of our political communities. If we fully exploit our material and spiritual inheritance, we can become decent citizens and loving parents, despite the constraints. We deserve from our political leaders a vision of our humanity that recognizes and celebrates this potential.

Such a spiritual argument is one that a social scientist may find hard to understand. Yet the spiritual resources of human beings are key to the maintenance of social stability and progress. They are the ultimate foundation of any hope we can have of overcoming the social malaise of the underclass. This is why the mechanistic determinism of science is, in the end, inadequate to the task of social prescription. Political science has no account of why people vote; psychology has yet to identify the material basis of religious exhilaration; economics can say only that people give to charities because it makes them feel good to do so. No analyst predicted that the people of Eastern Europe would, in Vaclav Havel’s memorable phrase, rise to achieve “a sense of transcendence over the world of existences.” With the understanding of causality in social science so limited, and the importance of matters of the spirit so palpable, one might expect a bit of humble circumspection from analysts who presume to pronounce upon what is possible for human beings to accomplish.

Whatever the merits of their social science, Herrnstein and Murray are in a moral and political cul-de-sac. I see no reason for serious conservatives to join them there. This difficulty is most clearly illustrated with the fierce debate about racial differences in intelligence that The Bell Curve has spawned. The authors will surely get more grief than they deserve for having stated the facts of this matter—that on the average blacks lag significantly behind whites in cognitive functioning. That is not my objection. What I find problematic is their suggestion that we accommodate ourselves to the inevitability of the difference in mental performance among the races in America. This posture of resignation is an unacceptable response to today’s tragic reality. We can be prudent and hard-headed about what government. can and cannot accomplish through its various instruments of policy without abandoning hope of achieving racial reconciliation within our national community.

In reality, the record of black American economic and educational achievement in the post-civil-rights era has been ambiguous—great success mixed with shocking failure. Myriad explanations for the failure have been advanced, but the account that attributes it to the limited mental abilities of blacks is singular in its suggestion that we must learn to live with current racial disparities. It 1s true that for too long the loudest voices of African-American authenticity offered discrimination by whites as the excuse for every black disability; they treated evidence of limited black achievement as an automatic indictment of the American social order. "These racialists are hoist with their own petard by the arguments and data in 74e Be// Curve. Having taught us to examine each individual life first through a racial lens, they must now confront the specter of a racial-intelligence accountancy that suggests a rather different explanation for the ambiguous achievements of blacks in the last generation.

So the question now on the floor, in the minds of blacks as well as whites, is whether blacks are capable of gaining equal status, given equality of opportunity. It is a peculiar mind that fails to fathom how poisonous a question this is for our democracy. Let me state my unequivocal belief that blacks are, indeed, so capable. Still, any assertion of equal black capacity is a hypothesis or an axiom, not a fact. The fact is that blacks have something to prove, to ourselves and to what W. E. B. Du Bois once characterized as “a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” This is not fair; it is not right; but it is the way things are.

Some conservatives are not above signaling, in more or less overt ways, their belief that blacks can never pass this test. Some radical black nationalists agree, arguing increasingly more openly now that blacks can never make it in “white America” and so should stop trying, go our own way, and maybe burn a few things down in the process. At bottom these parties share the belief that the magnitude of the challenge facing blacks is beyond what we can manage. I insist, to the contrary, that we can and must meet this challenge. I find it spectacularly unhelpful to be told, “Success is unlikely given your average mental equipment, but never mind, because cognitive ability is not the only currency for measuring human worth.” This is, in fact, precisely what Herrnstein and Murray say. I shudder at the prospect that this could be the animating vision of a governing conservative coalition in this country. But I take comfort in the certainty that, should conservatives be unwise enough to embrace it, the American people will be decent enough to reject it.

When I was young, I got the idea that I could run track in high school. I decided I would run the mile. All I needed was mental toughness. While I could run only an average 100-yard dash, I reckoned if I put 18 of those together, I would be a very good miler.

I quickly learned mental toughness wasn't enough. You break down physically. The oxygen doesn't make it to your leg muscles fast enough. It didn't take Einstein to predict that, but I really wanted to be on the track team.

Marathoners have polygenic patterns that correlate with endurance. Some of the kids at my school had genomes more in line with the marathoners than I did. Those kids didn't need mental toughness or drive or discipline to run circles around me.

I would have been doomed to a life of misery if someone had pushed me to make long-distance running the centerpiece of my life. Some people are tall, some are less so. Some are attractive, some are less so. Some people are smart, some people are less so. Some process oxygen super efficiently, some don't. Identify your strengths and do the best you can. There are a million paths to contentment.

A greyhound is going to be miserable if you make him jump in icy water and retrieve ducks. A Labrador retriever will go hungry trying to chase down rabbits in an open field. We need to stop trying to pound square pegs into round holes -- no matter how useful it might be politically.

The data and analysis in The Bell Curve is very impressive and not easily dismissed. It seems likely to me that the abilities being measured by the usual intelligence tests are real. There is a big part of those tests, however, that measures the person's "fund of information," which very probably varies with how widely read the person is, and that is in turn a function of other cultural variables.

I think that "success," especially financial success has more to do with what vocational paths people choose. One reason (but not the only one) why employed women earn less than employed men is that the work that interests more women than men tends to be less well paid. Work involving "service to others," especially kids, for example, tends to be underpaid. The same is true for traditional visual arts, such as painting and photography. Jobs that have paid well for men are not all knowledge based: contracting and self employment in small but growing businesses are examples.

This is a capitalist system pattern that is not necessarily related to supply and demand, but more to other factors. These factors include cultural valuation of certain kinds of work over others, and certainly also biases. Women have historically been expected to provide all of the childcare, nursing of the ill and dying, and so on, for free. The national loss of manufacturing jobs has been devastating for men and their families, as many of these jobs paid enough for families to live on one income.

With regard to the performance of black kids and adults, I always return to the fact that if kids are not consistently attending school, and not receiving enough support for academic achievement in their homes and neighborhoods, they will not perform anywhere near their capacities. And this is clearly the case, so the emphasis should be on motivation and what it takes to increase it.