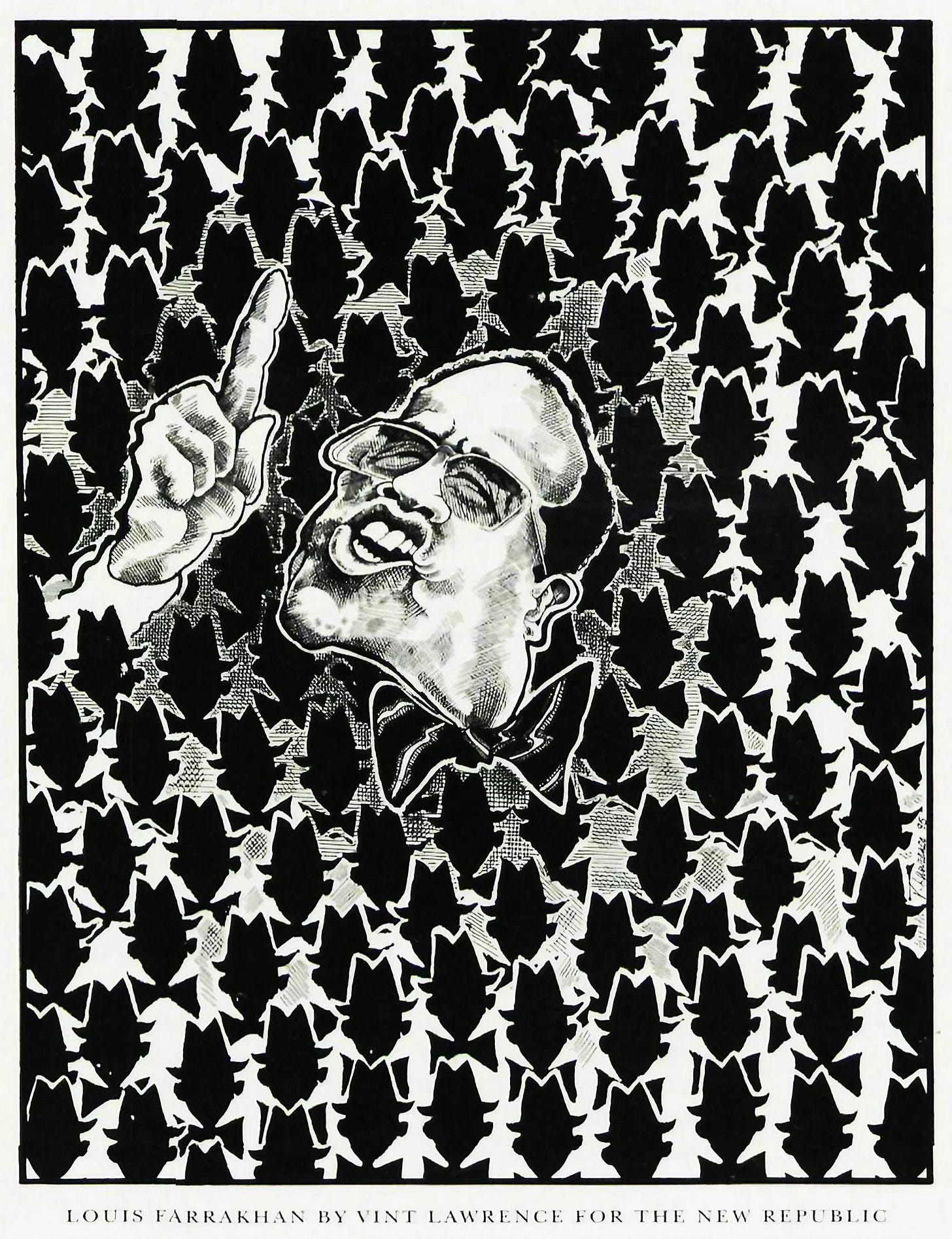

I was reading through some of Glenn’s essays the other day and came across this one, first published in The New Republic. In it, Glenn recounts observing Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March, which took place on October 16, 1995 on the National Mall in Washington, DC. None of the material in this essay is included in the memoir, but it contains some of the same themes, ideas, and characters: the tension between racial solidarity and individuality, the role of faith in the project of social uplift, and figures like Uncle Moonie, who shaped Glenn’s self-conception as a young man. I quite enjoyed it, and I think you will, too. And of course, there’s much more where this came from in Glenn’s memoir, out on May 14. Preorder it now from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, or wherever you get your books.

Mark Sussman

Editor

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

One Man’s March

by Glenn C. Loury

The New Republic, November 6, 1995

Try to understand my problem. I am a black intellectual of moderate to conservative political instincts. Unlike many of my racial brethren, I have been denouncing the anti-Semitism of Minister Louis Farrakhan for over a decade. (My virgin Farrakhan denunciation was in this very magazine in December 1984.) To judge from the volume of press inquiries in past few weeks, I must have been one of the few black men in America willing to state for the record my reservations about, and objections to, the Million Man March. I promiscuously expounded my view that it would not be possible to separate the message from the messenger and that, in any case, a race- and sex-exclusive march would send the wrong message. In short, my credentials as a “deracinated Negro,” able to steadfastly resist the call of tribe, are impeccable.

Imagine my surprise, then, when on the day before the march, as I walked along the Mall from the White House toward the Capitol encountering other black men in town for the event, I found myself becoming misty. I watched these “brothers,” in clusters of two or three or six, from Philadelphia and Norfolk and my own hometown of Chicago, wandering among the museums and monuments like the tourists they were, cameras in hand, and the sight brought tears to my eyes. The march had not even begun, and already powerful sentiments, long buried inside me, were being resurrected. I knew then that I was in trouble.

Here were young black guys, the same ones occasionally mistaken by belligerent police officers or frightened passersby for threats to public safety because of the color of their skin and the swagger of their gait, scrambling up the steps and lounging between the columns of the National Gallery building, some even checking out the “Whistler and His Contemporaries” show on display inside. And there were others, sharing an excited expectancy with Japanese tourists and rural whites as we all waited in line to tour the White House. Taking in these various scenes, an obvious but profound thought occurred to me: this is their country, too. So embarrassed that I needed to remind myself of this fact, I wept.

The next day, as I beheld hundreds of thousands of black men gathering in a crowd that ultimately stretched from the steps of the Capitol back toward the Washington Monument, I would be even more deeply moved. Everything that has been said about the discipline and dignity of the gathering, and the spirit of camaraderie that pervaded it, is true. It was a glorious, uplifting day, and I was swept up in it along with everyone else. It almost did not matter what was being said from the podium. For the first time in years, as the drums beat and the crowd swayed, I heard the call of the tribe, big time.

Mingling in that throng, my thoughts drifted back to my late Uncle Moonie, the husband of my mother's sister, who, as head of the extended household in which I was raised, exerted a powerful influence on me in my formative years. Uncle Moonie, so called because his large, round eyes protruded like half-moons beneath his often furrowed brow, was a barber, part-time hustler and admirer (though not a follower) of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam. My uncle kicked a nasty heroin habit in his youth and went on to achieve what was for his generation of black men an impressive degree of financial security. Fiercely proud and independent, he constantly railed against “the white man,” and he never tired of berating those blacks who looked to “white folk” for their salvation. Occasionally he would take me with him to the state prison for his monthly visits with one or another of his incarcerated friends. “There, but for the grace of God, go you or I,” he would say. He encouraged me in an intelligent militancy and even sought to extend his influence from beyond the grave by bequeathing to me one of his most cherished possessions—a complete set of the recorded speeches of Malcolm X. Had Uncle Moonie lived to attend this march, he would have thought it the greatest experience of his life.

To be sure, my uncle would not have understood my public criticism of the march or of Minister Louis Farrakhan, for that matter. He was no great fan of the nonviolent philosophy of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. He much preferred the straight-backed, unapologetic defiance of Malcolm. He would have been puzzled that I could find the opinions of “white folks” worth taking into account. He would have rejected the notion that there are ethical and political principles my fealty to which could transcend my sense of racial loyalty.

In short, were he alive today, I fear that Uncle Moonie would be profoundly disappointed in me. Still, those tears welling in my eyes at the sight of “our brothers” on the Mall might have given him hope that I could yet be redeemed. The tingle that ran up my spine as I beheld that massive assembly of beautiful black men seeking unity and spiritual upliftment caused me to hope, for a fleeting moment, that I could, at long last, go home again.

My pre-march analysis was a tight little piece of amateur political theory that ran as follows: the problem with the Million Man March is that it mixes communal and political activities inappropriately. As a communal matter, a religiously motivated gathering of men seeking to commit themselves to reconstruction and renewal in their personal lives and in their respective neighborhoods, it is highly commendable. However, as a political matter, gathering on the Mall at the site of the great 1963 March on Washington—but now as black men and not as Americans, under the leadership of a Louis Farrakhan not a Martin Luther King—this is deeply problematic. The sacrifice of liberal democratic ideals and the separatist message is too high a price to pay for getting our cultural trains to run on time.

Yet, when put to the test on the Mall, this elegant bit of theory seemed to collapse instantly under the weight of a single fact: nearly one-half million African American men had solemnly, prayerfully assembled to affirm their intention to take responsibility for the condition of their people.

As a social critic, I have called for many years for the civil rights leadership to reorient itself from a focus on the “enemy without,” white racism, toward the “enemy within,” the dysfunctional behaviors of young black men and women that prevent too many from capitalizing on existing opportunity. Well, here were some 5 percent of the age-adjusted national black male population, together in one place, supporting this very idea. Standing there, and listening to their collective affirmations, I found it hard to deny that the conception and execution of this event had been a work of genius. In the heat of those moments, I felt confused about my ideals and commitments and deeply ashamed to have spoken against the march.

However, I have been an economist for more years than I have been a social critic. As such, I have learned well the art of tenaciously holding on to a theory that, by virtue of its elegance and appeal to intuition, “ought to be true,” even when it seems inconsistent with the facts. The key is to find another way of looking at the evidence that casts one's favored theory in a better light. That is not difficult in the case at hand, for what seemed at that march like the salvation of black Americans is, upon closer examination, no such thing at all.

Begin with a simple question: How did it come to pass that this great moment in American cultural politics was orchestrated by the demagogic leader of a black fascist sect, while no other nationally prominent black leader could have pulled it off? The answer is two-fold. First, Farrakhan, whatever one thinks of him, is a religious leader, speaking to a flock desperate to hear an explicitly spiritual appeal. The Nation of Islam has a track record of “turning the souls” of a great many underclass men, especially in prisons. In contrast, liberal black political leaders, ironically drawn substantially from the clergy, have checked their ideologically conservative Christian witness at the door of the Democratic Party. In coalitions with feminists, gays and radical secularists, and in reaction against the politics of the religious right, they have muted their voices on social issues, leaving a void in black public life that Minister Farrakhan has adroitly filled.

Secondly, Farrakhan's message of spiritual uplift is deeply rooted in a white-man-has-done-us-wrong grievance politics. He does not ask blacks to give up the latter as he proffers the former. In this, he is being faithful to his teacher, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who taught that the white man is a blue-eyed devil, a mutant breed created by the mad scientist Yakub and allowed by God to rule over the superior black man until such time as the black man would return to the true faith. No serious persons, inside the Nation of Islam or out, could take this literally. But the premise that blacks find our reason for being in the fact of our enslavement and subsequent persecution anchors all that the Nation of Islam undertakes. This narrow, reactive self-conception is glorified as manly, truth-telling, clear-eyed realism.

Thus, forcing myself to listen carefully to what the speakers at this massive gathering actually said, I began to fear that, notwithstanding the emotion of the moment, nothing will really change. We all pray that one-half million inspired black men will return to their cities and towns, redouble their efforts and with the help of their women create nurturing families and community-based institutions that will change the awful facts on the ground. But do we have any warrant, based upon what was said from the podium, much of it cliched, resentful and conspiracy-laden, to believe this will transpire?

Uncle Moonie has been dead nearly fifteen years now. His was a different, harder time for black men. That he admired Elijah Muhammad is not surprising, given the context of his life. Now, removed from the passions of the march, and having had the opportunity to reflect, I believe that my passionate rejection of racial essentialism was right for me and, given the context of our lives today, for “my people.” The American people, that is.

There are now one and a half million Americans behind bars. This seems to me a tragedy of enormous proportions. Our cities are filled with poor, uneducated young people, wandering the streets aimlessly and without hope. This is a blight that graphically reveals the failure of our political leadership. We now celebrate in our politics the state-sanctioned, eye-for-an-eye taking of human life via capital punishment and the arbitrary locking away for a lifetime of those who have made but three mistakes. I think that this is an abomination unworthy of a civilized nation. So do the organizers of the march. But, unlike them, I do not believe that our outrage should depend on the racial identity of those who suffer. What is morally significant is that they are human; their claim on our attention derives from this fact alone.

The call of the tribe is seductive, but ultimately it is a siren call. As comforting as the prospect may seem, the truth, for all of us, is that we can't go home again. For blacks, as Ralph Ellison has taught us, “our task is that of making ourselves individuals. . . . We create the race by creating ourselves and then to our great astonishment we will have created a culture. Why waste time creating a conscience for something which doesn't exist? For you see, blood and skin do not think.” This is the fundamental point. Skin and blood do not think, or dream, or love or pray. The “conscience of the race” must be constructed from the inside out, one person at a time. I did not hear this sentiment expressed by a single speaker at the Million Man March.

Glenn Loury is a decent man and a brilliant economist. That he can decipher and select the wheat from the chaff founded in present day African-American dysfunction, is impressive. In my opinion Glenn is absolutely right over the target. As a white man of conservative values and a supporter of the US MAGA movement, I will have no truck with racism. Americans are Americans and the sooner they drop the African moniker the better. It is "the content of character" that matters.

Incredibly powerful and moving. These tensions are to some degree inevitable but it's rare to see them articulated this clearly and thoughtfully.