What Comes after Race-Conscious Admissions?

Clifton Roscoe weighs in on affirmative action

Racial preferences in college admissions may be on the way out, but Clifton Roscoe is back! When the Supreme Court hands down its decision on the recent Harvard and University of North Carolina cases, affirmative action may change dramatically. I think that’s a very good thing, but it doesn’t mean we no longer have to think about race and education. As Clifton makes clear in this piece, the real problem has always been the lagging academic achievement of black K-12 students. Fixing that issue is much more difficult than adjusting college admissions standards in order to create “diverse” cohorts. That strategy may not any longer be feasible, and we’ll have to take a harder look at how African American students are learning at a younger age.

Here Clifton offers his characteristic blend of hard data and stark realism. Facing the problems he outlines head-on may require a wholesale shift in our country’s way of thinking about how we measure success. It may be a painful process, but it’s a necessary one.

I’ve also weighed in on affirmative action at length in the latest issue of City Journal. My contribution will be available online soon, but get your hands on a hard copy if you want to read it now.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

This week’s arguments in the Harvard and University of North Carolina Supreme Court cases have made it clear that racial preferences in college admissions aren’t long for this world. The public favors racial diversity, but only if it's achieved in a way that's fair to everybody. In order to achieve that goal, we first have to build a robust pipeline of highly qualified black college applicants. That won't be easy. A 2006 paper by Derek Neal of the University of Chicago showed that the black-white skill convergence stalled out during the late 1980s. Here's the abstract from Neal's paper:

All data sources indicate that black-white skill gaps diminished over most of the 20th century, but black-white skill gaps as measured by test scores among youth and educational attainment among young adults have remained constant or increased in absolute value since the late 1980s. I examine the potential importance of discrimination against skilled black workers, changes in black family structures, changes in black household incomes, black-white differences in parenting norms, and education policy as factors that may contribute to the recent stability of black-white skill gaps. Absent changes in public policy or the economy that facilitate investment in black children, best case scenarios suggest that even approximate black-white skill parity is not possible before 2050, and equally plausible scenarios imply that the black-white skill gap will remain quite significant throughout the 21st century.

A look at NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) trends supports Neal's conclusion and shows how little progress has been made in K-12 over the past 30 years. What was a 32-point gap in math scores between black and white 4th graders in 1992 was a 29-point gap in 2022:

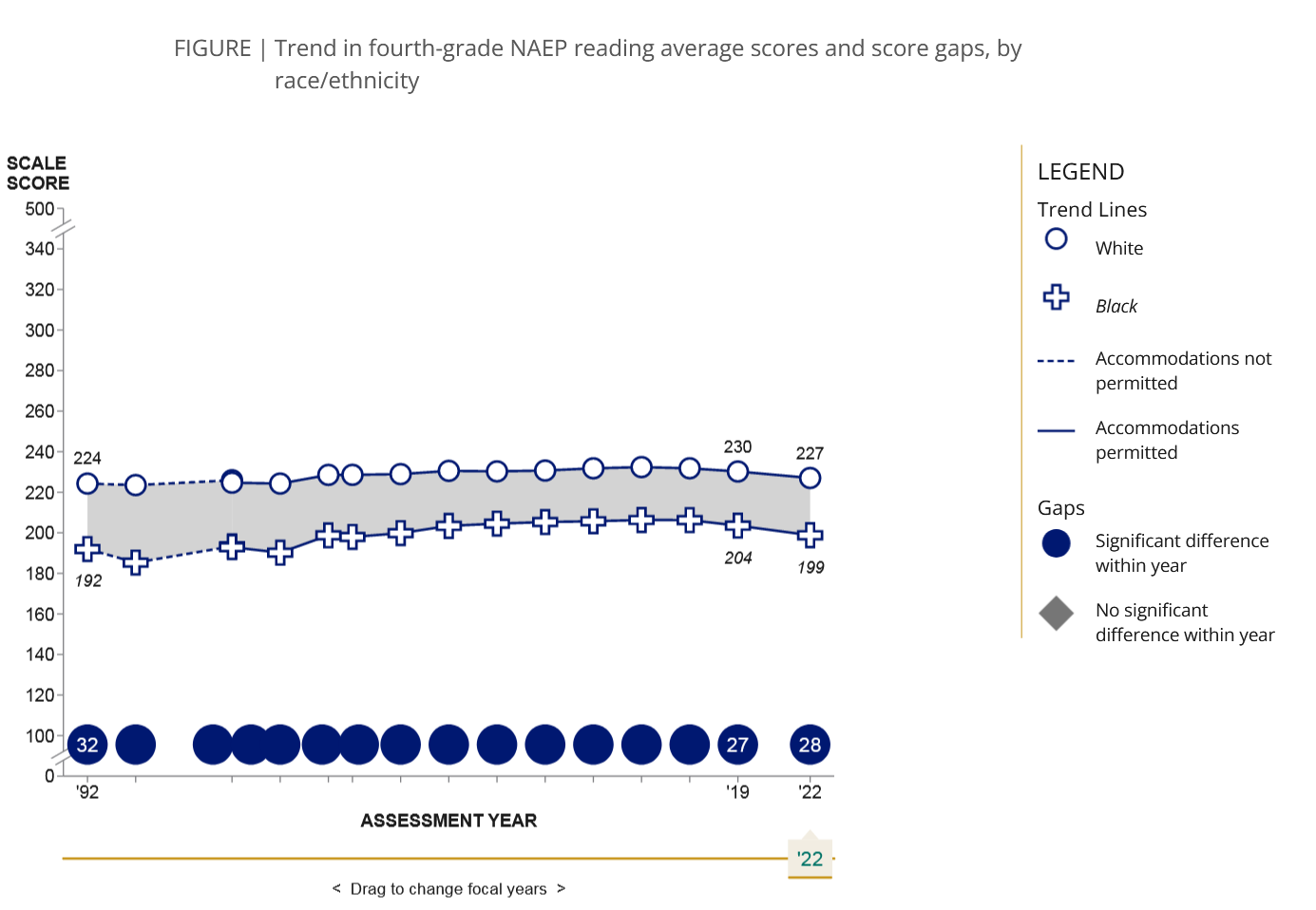

What was a 32 point gap in 4th grade reading scores in 1992 was a 28 point gap in 2022:

Ten points is the equivalent of about a year's worth of learning, so these results suggest that black 4th graders have been about three years behind their white peers in math and reading for the past three decades. That roughly corresponds to Derek Neal's finding that the black-white skill convergence stalled out in the late 1980s.

A look at the scores for 8th graders shows a similar pattern. What was a 33-point gap in math for 8th graders in 1992 was a 32-point gap in 2022:

The gap in reading scores for 8th graders closed a bit. What was a 30-point gap in 1992 was a 25-point gap in 2022:

That said, these results suggest that black 8th graders have been two to three years behind their white peers in reading and math for three decades.

These racial gaps persist through high school. College readiness assessments from ACT show a large gap for the Class of 2022. Here's a summary of the percentages of high school seniors who met all four college readiness benchmarks (e.g., English, Math, Reading, Science):

All students: 22%

Black students: 5%

White students: 29%

Hispanic/Latino students: 11%

Asian students: 51%

These figures came from Table 3.3 of ACT's 2022 National Profile Report. Some people question the validity of these assessments, but a look at college completion rates confirm their predictive power. Here's a graphic and an excerpt from the NCES (National Center for Education Statistics):

The 6-year graduation rate for first-time, full-time undergraduate students who began their pursuit of a bachelor’s degree at a 4-year degree-granting institution in fall 2010 was highest for Asian students (74 percent), followed by White students (64 percent), students of Two or more races (60 percent), Hispanic students (54 percent), Pacific Islander students (51 percent), Black students (40 percent), and American Indian/Alaska Native students (39 percent).

The 1990 Student Right to Know Act requires degree-granting postsecondary institutions to report the percentage of students who complete their program within 150 percent of the normal time for completion (e.g., within 6 years for students seeking a bachelor’s degree). Students who transfer without completing a degree are counted as noncompleters in the calculation of these rates regardless of whether they complete a degree at another institution. The 6-year graduation rate (150 percent graduation rate) in 2016 was 60 percent for first-time, full-time undergraduate students who began their pursuit of a bachelor’s degree at a 4-year degree-granting institution in fall 2010. In comparison, 41 percent of first-time, full-time undergraduates seeking a bachelor’s degree received them within 4 years and 56 percent received them within 5 years.

NOTE: Data are for 4-year degree-granting postsecondary institutions participating in Title IV federal financial aid programs. Graduation rates refer to students receiving bachelor’s degrees from their initial institutions of attendance only. The total includes data for persons whose race/ethnicity was not reported. Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Although rounded numbers are displayed, the figures are based on unrounded data.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), Winter 2016–17, Graduation Rates component. See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, table 326.10.

The data reveal a less-than-robust pipeline of highly competitive black college applicants. Colleges and universities have used race when making admissions decisions to partly offset this problem. They've also turned to black immigrants to reach their diversity goals. That seems to be especially true for America's most selective colleges and universities. Robert Cherry made this point in a RealClearEducation column from last month. As he says, affirmative action at these schools is “no longer justified as compensation for slavery and institutional racism, but solely for its potential impact on diversity.” At the same time, “the most selective schools stopped reporting on the ethnicity of their black student population.”

This is not a new issue. I'm not critical of black immigrants, but the rationale for using race when making college admissions decisions was to create more opportunities for native born American blacks, not black immigrants.

Black Americans won't achieve equality with their peers until the pipeline of highly competitive black college applicants is filled. Papering over the problem using the college admissions process is no longer feasible, legally or politically. The Supreme Court seems to be poised to abolish this practice, and polling suggests that a majority of the public agrees with them.

Here are two graphics from a Pew Research analysis that show a majority of Americans oppose the use of race as a factor when making college admissions decisions:

The analysis from Pew shows that a majority of blacks oppose the use of race in college admissions decisions. A new Washington Post-Schar School poll says 47% of blacks oppose the use of race in college admissions decisions. It also says that over 60% of whites, Latinos, and Asians feel the same way.

Why have colleges and universities taken a position that runs so contrary to public opinion? They've apparently convinced themselves that racial diversity is important and necessary in the pursuit of their missions, but it's not clear what their missions are or why racial diversity is more important than other forms of diversity.

This week’s oral arguments before the Supreme Court were revealing. An attorney defending the use of race in making admissions decisions struggled to answer questions from Justice Thomas about the definition of diversity and how it enhances the education of students.

A YouGov poll asked respondents how they felt about 10 types of campus diversity:

1. Economic diversity

2. Ability diversity

3. Racial diversity

4. Social class diversity

5. Geographic diversity

6. Gender diversity

7. Age diversity

8. Sexual orientation diversity

9. Religious diversity

10. Political viewpoint diversity

There wasn't much support for using any of them when making admissions decisions. Here's an excerpt:

Should colleges and universities consider any types of diversity in admissions decisions? For nearly all of the 10 diversity considerations polled, majorities of Americans responded that they should not be considered by colleges and universities when admitting students. Only about one-third of Americans want economic (34%), ability (32%), or racial (31%) diversity to be considered. Racial diversity is the type most likely to be backed by Democrats (53%), followed by economic diversity (51%) and ability diversity (48%). Majorities of Republicans reject each of the options presented, with the closest margin for ability diversity (23% say yes, 59% say no).

It will be almost impossible for colleges, universities, employers, and most of our institutions to reach their racial diversity goals without lowering standards for black applicants until more black K-12 students are competitive with their peers. Not many people are willing to say this out loud, but the data speak for themselves. We should have a robust debate about this issue and the tradeoffs associated with tilting the playing field to help those who are underrepresented in our institutions.

There's an old expression that says a kick in the pants can be a step forward. What some think will be an adverse decision from the Supreme Court may prompt a more explicit conversation about these issues and a much needed focus on addressing the root causes of the problem.

All I have is my personal observations over the last 45 years. I have an MS in Chemical Engineering (guess how many women were in Engineering in the 1970’s). When I had my first supervisory job in 1982 I was assigned a black student in a program sponsored by major companies in St. Louis to help prepare black students to succeed in Engineering. She came from a more privileged background than I did, she came from a better neighborhood than I grew up in And she had far more money for clothes than I had had when I was in school. Her parents both had college degrees. But she was not a reliable worker. She was consistently late to work. She had no initiative to do anything on her own. I thought she might be an exception in the program until I went to the year-end banquet. The companies had contributed large sums of money to sponsor scholarships for the students in the program. Participants with C averages were getting scholarships. It was ridiculous. Should she really receive preference over someone like me that had a less privileged background, had top SAT and ACT scores and grades but was white? The only message these students received was they could not work and still get rewarded.

We moved to Charleston SC in the 1990’s and I became active in my daughter’s school. My observation in that school was the average black child had significantly lower academic capability and that black parents did not care about the outcomes of their children. As president of the PTA I actively tried to recruit black parents to participate on the board or at PTA meetings. While we had no difficulty getting white or Asian parents to participate (they volunteered) it was almost impossible to get black parents. The usual excuse by white liberals is that the black parents have to work. Well, most of the white parents participating had full time challenging jobs, At one PTA meeting a black child had a major role in the meeting. Not one person from her family came to watch. No one even came to pick her up. After the meeting I was the one to give her congratulations and give her the attention someone in her family should have given the sweet girl. We had to hunt up someone from her family to even pick her up. I could identify with the little girl because I was frequently forgotten and no one picked me up either.

My observation is that success in any activity is a combination of innate talent and willingness to work. If you are short in innate ability you have to work harder to get the same outcome as someone more talented. You cannot control your innate ability but you have total control over how hard you work. The major company I worked for essentially did an IQ test before hiring hourly workers. I rank ordered all those working for me and correlated that with their employment test results. My top rated employee was a black technician. He had one of the lowest test scores but he never missed work, followed the test instructions exactly every time and if he had any questions about results he consulted with one of the chemists. He was highly valued and appreciated but didn’t belong in an Ivy League school and I didn’t value him any less for not going to one.

My church has a mentoring program for minority students and I participated in that for two years. My conclusion from that experience is again the parents are the problem. The mother was in the program to see what freebies she could get out of the program, not how it could hep her daughter. She thought I would be the goose who would lay the golden eggs for her. An example, I tried to have the little girl do chores with me so she could earn money to buy everyone in her family gifts for Christmas. She made a list of what she wanted to get them. I had to contribute most of the money but at least she did some work and I hoped she would connect the work with being able to give something to her little brothers. Her mother wanted the receipts so she could return everything and get the money for herself. How is any school going to make up for that influence? I spent 5 hours a week with her. She was with her family the rest of the time.

I would like to see a study on how welfare affected the outcomes for lower classes. Johnson started the Great Society programs in the 1960’s. The negative outcome from those programs would start to show up in the 1980’s. Everyone is a unique individual with great value, regardless of their particular skill sets. There is something very wrong in measuring diversity by skin color and not by experiences, contributions and ideas.

For those thinking more money is the solution guess again. At least in Charleston, schools in minority areas get a lot more resources. They have more teachers, more specialists, better equipment, more of everything but still have worse outcomes. The school shutdowns from Covid are going to have even a worse outcome on these students.

I think the only criteria should be what is going to best serve the child/student. The percent of minorities attending selective universities is not a measure of this.

There is very little appetite in modern America to solve the skills gap between black children and everyone else because black misery and underperformance is so profitable to so many people even tangentially associated with the educational establishment.

My wife, who is African, not African-American, is currently teaching first grade at a neighborhood public school here in Detroit. She will have 20-25 students on any given day.

Three or four of them are what we used to call "bad" kids: no discipline, no respect, no interest in learning. They are sent to school by the parents not to learn but to be bay-sat. The school administration accepts, and coddles these children because every set of buttocks that is filling a chair on "count day" is worth $10k + to the district. It is difficult to be suspended, and impossible to be expelled, no matter how egregious the behavior .

Those few bad kids get most of the teacher's attention, by default. The rest of the students try to get by with the scraps that are left once the disruptive knuckleheads have been dealt with.

For the limited time that is devoted to actual instruction, the public schools here are forced to use textbooks that seem to have as their main objective the desire to confuse the students and discourage learning, I am no genius, but I should be able to decipher first grade material, and I can't. The books are written by "experts" whose careers depend on the endless updating of their material, with copious amounts of interventions from early learning "specialists":, "achievement coaches" and so on. No one, absolutely no one cares about the implications of subjecting generations of children to this BS. They only care about checking boxes and advancing careers. The bulk of the credentialed professionals here in Detroit have long ago forgotten that the purpose of teaching used to be to provide children with the fundamental tools to go out into the world and be able to make their lives in it.

Then you have the parents...most of whom simply do not care one tiny little bit about their child's progress, or lack thereof. There are, clearly, exceptions, but they are, just as clearly, exceptions. And while having two parents who care and who are there might be preferable, that isn't necessary. My wife never knew her father, and grew up in a poverty that is simply unimaginable to anyone in America today, and yet she is now in Detroit, teaching English (her third language) to American children. The difference is that in Africa, schooling is a sought-after privilege, teachers are respected, bad behavior is not tolerated, and black African children are not schooled to believe that they are incapable of excellence because of their "victim" status.

School choice will help, as will the ending of all racial preference programs, but the biggest change will necessarily have to come from the parents themselves, who will have to discover the will to demand excellence from their children, teachers, and themselves, and not accept the permanent underclass status that is intrinsic to a culture of low expectations.