Almost 38 years ago, I published an essay in Commentary magazine on what seemed to me a pressing issue: the diverging political paths of African Americans and American Jews. In the 1950s and ‘60s, some of the most energetic allies of the civil rights struggle were Jewish. Jews marched alongside blacks, volunteered in on-the-ground efforts to organize and register black voters, and publicly advocated for black interests. This took considerable courage, since Jews themselves were still frequently the victims of discrimination in the US, and elements of the Civil Rights Movement were unpopular even in the North. They had little to gain and much to lose, including their lives, and yet they acted because they felt compelled to, whether by political belief, the recent memory of the Holocaust, religious conviction, or a simple recognition that the cause was righteous.

Some twenty years later, it seemed to me, an alliance that had once served as a high point of America’s pluralistic potential was falling apart. In the Commentary essay, I identified disagreements over affirmative action and Israel-Palestine as two of the most charged sites of conflict between American Jews and blacks. Looking back on the past year, it strikes me that these two issues have once again emerged as areas of dispute. I’ll not embark on an extended meditation on affirmative action and Israel-Palestine today. I’ve said plenty already this year, and there will be much more to say going forward. For now I present the text of my 1986 essay, “Behind the Black-Jewish Split.” I do not know whether, all these years later, I should feel proud of the essay’s prescience or dispirited by its continuing relevance.

This post is free and available to the public. To get early access to episodes of The Glenn Show, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, comments, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

Behind the Black-Jewish Split

Originally published in Commentary, January 1986

Relations between American blacks and Jews have become strained in recent years. These two groups, long allies in the historic struggle for social justice in this country, find themselves now at loggerheads over issues which each perceives as vital to its interests. Demagogues have magnified these differences; distrust and ill-will are now much more common in our dealings than was the case two decades ago. Efforts have been made to repair the damage, to restore the old comity but mostly in vain. And just beneath the overt expressions of disappointment and disagreement one senses that there are feelings of betrayal, ingratitude, and disloyalty. Some blacks, it would appear, feel betrayed by Jewish opposition to quotas, by Israel's relationship with South Africa, by the advent of a “Jews Against Jackson” committee. Some Jews seem to view black support for the PLO as ingratitude in the face of the contributions to the struggle for civil rights which Jews have made over the years, and are alarmed by the reluctance of black political figures to denounce Louis Farrakhan—a reluctance which to them appears a tacit acceptance of black anti-Semitism.

Some of the problems between the groups go back many decades. For example, due to the process of residential segregation and ethnic succession in urban areas, blacks often found themselves moving into neighborhoods which had previously been Jewish, renting from Jewish landlords, buying from Jewish merchants. Tenants and landlords, buyers and merchants naturally have a certain opposition of interests, and that opposition is magnified if each tends to be predominantly of a distinct group, and if there are clear differences of economic class between them. Many blacks perceived these relationships as exploitative, and undoubtedly in some cases they were. Many Jews looked on their black patrons—poorer, sometimes recently arrived from the South—with fear, or disdain. James Baldwin was already writing about this black-Jewish problem in the 1940's.

Similarly, the influx of poorer blacks into Jewish residential areas created problems for many Jews, who found themselves victims of criminal offenses perpetrated by young black men, or who became gripped by the fear of such victimization. Elderly Jews, less mobile than their younger brethren, found themselves trapped in their apartments, afraid to venture onto the street, and blaming the “schvartzes”—the blacks—for their plight. Jewish boys attending public schools with blacks would have their lunch money taken, or be chased home by tougher black youths at the end of the day. Norman Podhoretz was writing about this—his “Negro problem”—nearly a quarter of a century ago (and well before even a hint of a neo-conservative critique of blacks' public claims had emerged).

So there have always been tensions, arising out of fear, envy, and resentment of exploitation. Yet in years past such inevitable difficulties as these were not allowed to obscure what was a deeper, more fundamental commonality of interests between the two groups—their shared revulsion for and struggle against officially sanctioned racism and discrimination; their leaders' shared commitment to a common agenda for American public life. It is this absence of shared public visions, however distinct our private beliefs and values have always been, which to my mind represents what is new (and ironic) about the current state of black-Jewish relations. For the structural, economic basis for tension between the groups has diminished substantially from what it was twenty years ago—innercity landlords and merchants are no longer mainly Jews, and (outside of New York City) those neighborhoods in which Jews were likely to have unfavorable experiences with their black neighbors have mostly vanished with the upward mobility and suburbanization of the Jewish population. Moreover, the collective effort to make it impossible that bigotry might find an honorable place in American public life has largely succeeded. Yet in the aftermath of this shared victory, and with a diminished immediacy of the interpersonal conflicts between individual blacks and Jews, there seem to be more bad blood and fewer common visions between the groups now than ever before.

I submit that there are two primary reasons for this state of affairs. The first I associate, though perhaps not in the expected way, with the advent and diffusion through our polity of racially preferential employment and admissions policies. From its very inception, affirmative action—at least in the sense of racial preference—has been a policy at once avidly embraced by blacks and reflexively distrusted by Jews. (I say this knowing full well that many Jews support affirmative action in this sense and many blacks oppose it. But broadly my generalization seems true.) Blacks have, on the whole, seen the use of quotas in employment and education as a necessary and just recompense for the wrongs of history. Jews have feared such practices, seeing in them an echo of the anti-Jewish quotas of the past and a threat to their standing in the professions.

But I think the issue of affirmative action has exacerbated the black-Jewish rift for deeper, more fundamental and intractable reasons than this. Nathan Glazer has persuasively argued that affirmative action ought to become less divisive for blacks and Jews since now many Jews (namely, Jewish women) benefit directly from the policy, and because as the Jewish occupational profile has moved away from teaching and the local civil services, the direct threat to Jewish interests posed by affirmative action has diminished. Moreover, as the practice of affirmative action and racial preference has become broadly entrenched in American society, opposition to it on the political level has become so widespread that it is difficult to single out Jewish Americans as particular “offenders” in this regard.

One can certainly hope that Glazer is right. Yet I maintain that, much more important than the direct conflicts of interest around the affirmative-action issue are the symbolic and ideological differences between the groups which this policy brings to the fore, together with the kinds of asymmetrical relations among intellectual elites in the two groups which it fosters. That is, the policy of racial preference forces blacks and Jews publicly to confront their very different understandings of the American experience.

Racial preference to many blacks finds its essential rationale in an interpretation of history: that blacks have been wronged by American society in such a way that justice now requires they receive special consideration. Yet this reparations argument immediately raises the question: why do the wrongs of this particular group and not those of others deserve recompense? While more or less plausible responses to this query have been offered, no amount of recounting the unique sufferings attendant on the slave experience can make the question go away. For it is manifestly the case that many Americans are descended from forebears who had, indeed, suffered discrimination and mistreatment at the hands of hostile majorities both here and in their native lands. Yet these Americans on the whole have no claim to the public acknowledgment and ratification of their past suffering, as do blacks under affirmative action. The institution of this policy, rationalized in this way, therefore implicitly confers special public status on the historic injustices faced by its beneficiary groups, and hence devalues, implicitly, the injustices endured by others.

The public character of this process of acknowledgment and ratification is central to my argument. We are a democratic, ethnically heterogeneous polity. Racial preferences become issues in local, state, and national elections; they are the topic of debate in corporate boardrooms and university faculty meetings; their adoption and maintenance require public consensus, notwithstanding the role that judicial decree has played in their propagation. Therefore, the public consensus required for the broad use of such preferences results, de facto, in the complicity of every American in a symbolic recognition of extraordinary societal guilt and culpability regarding the plight of a particular group of citizens. And failure to embrace the consensus in favor of such practices invites the charge of insensitivity to the wrongs of the past or, indeed, the accusation of racism.

But perhaps most important, the public discourse surrounding racial preference inevitably leads to comparisons among the sufferings of different groups—an exercise in what one might call “comparative victimology.” Was the anti-Asian sentiment in the Western states, culminating in the Japanese internments during World War II, “worse” than the discrimination against blacks? Were the restrictions and attendant poverty faced by Irish immigrants to Northeastern cities a century ago “worse” than those confronting black migrants to those same cities some decades later? And ultimately, inevitably, was the Holocaust a more profound evil than chattel slavery?

Such questions are, of course, unanswerable, if for no other reason than that they require us to compare degrees of suffering and extents of moral outrage as experienced internally, subjectively, privately, by different peoples. There is no neutral vantage point from which to take up such a comparison.

Yet many critics of racial preference can be heard to say “our suffering has been as great”; and many defenders of racial quotas for blacks have become “. . . tired of hearing about the Holocaust.” These are enormously sensitive matters, going to the heart of how each group defines its collective identity. James Baldwin, writing in the late 1960's on this subject, declared what many blacks believe: “One does not wish to be told by an American Jew that his suffering is as great as the American Negro's suffering. It isn't, and one knows it isn't from the very tone in which he assures you that it is.” And when, in 1979, Jesse Jackson visited Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, he deeply offended many Jews with what he may have considered a conciliatory remark—that he now better understood “. . . the persecution complex of many Jewish people that almost invariably makes them overreact to their own suffering, because it is so great.” By forcing into the open such comparative judgments concerning what amount to sacred historical meanings for the respective groups, the policy of racial preference has fostered deeper, less easily assuaged divisions than could ever have been produced by a “mere” conflict of material interests.

Moreover, the public debate over quotas brings into the open implicit historical comparisons of the extent to which different groups have been able to cope with the adversities of being marginal in American life. The idea that such preference is not only just, but necessary for some groups, seems to imply that they are less able than those coming before to adapt to the vicissitudes of life in our nation. Stories of despised immigrant outsiders, barely speaking the language and meeting resistance at every turn, but nonetheless overcoming the barriers and rising to middle-class status, are a commonplace of American folklore. And who can say with certainty that the barriers facing East European immigrants at the turn of the century were substantially less than those facing blacks (or Southeast Asian immigrants) today? When confronted with the continued, dramatic inequality experienced by some black Americans today, some two decades after the civil-rights revolution—an inequality which figures prominently in the argument that preferential policies are necessary as well as right—many ethnic Americans (and not only Jews) wonder why “they” can't do what “we” did.

Here, too, it is not important for my argument that plausible answers to such questions can be given—they certainly can be. What is critical is that the questions ever arise in the first place, for they are painful questions for blacks to contemplate. Nothing can be more calculated to incite a black audience to riotous objection than the claim that “The Jews [or Asians, or West Indians, or Irish Catholics] overcame racism and discrimination. Why can't you?” The most frequent response—“But they didn't suffer as we did”—throws us back into the dilemmas of “comparative victimology” discussed above. Such inevitably divisive public discourse is unavoidable once we undertake to practice preferential treatment based on historic injustice. This practice forces us to make public comparisons of and judgments about historical experiences of the utmost importance to each group's private sense of identity, pride, and historical violation.

There are also more prosaic reasons why this policy should be implicated in current black-Jewish difficulties. One consequence of affirmative action has been that large numbers of middle-class, well-educated, upwardly-mobile, and racially-conscious blacks have been thrust into highly competitive academic and professional environments in which Jews have flourished for decades, and in which Jews are vastly “overrepresented” in comparison with their proportion of the population. In such competition blacks often fare poorly. Jewish interest in and excellence at scholarly and professional pursuits are long-standing and well known, while black “underrepresentation” and marginal performance in these pursuits are also prominent features of the contemporary American social scene. When admissions to, say, law school are made in part to assure that blacks are well represented (assuming that the non-racial criteria of selection are actually predictive of performance after admission), a logically necessary consequence is that the average level of performance of those blacks admitted within the entering class will be lower than would have been the case absent racial preference. Another result is that, since “marginal” Jewish admissions are very few, those Jews admitted will exhibit, on the average, higher performance than would have obtained absent the quota.

The fact is that in many law schools (and we must not underestimate the importance of law schools as the crucible of character formation for tomorrow's political elites), black students on the whole cluster near the bottom of their classes, and Jewish students cluster near the top. Similar patterns are to be observed in academic performance at elite colleges and universities. This generalization is not without exceptions, and certainly need not reflect any inherent differences in individual capacities, but it is nonetheless broadly true. The asymmetries of power, status, and security inherent in this situation invite attitudes of condescension and contempt, of resentment and envy—and this among the future leaders and opinion-makers of each group. These attitudes are only compounded when school administrations attempt to respond to such inequities in performance through, for example, racial quotas on Law Review appointments and the like.

Thus, it seems to me that the advent of racially preferential policies has created a new basis for black-Jewish enmity, quite apart from the opposition of economic interests which one naturally looks to as the source of the difficulty. This new conflict is more dangerous because it involves essentials of human existence which are not easily compensated, if lost—dignity, self-respect, and the public acknowledgment and ratification of private, historical meanings.

The idea of public visions in conflict, which in essence is the theme of my argument, points to what I see as the other principal source of our current difficulties—what might be called conflicting nationalisms. It is curious that this should be so among two groups as thoroughly American as Jews and blacks. Yet two parallel developments have brought this long dormant source of tension between the groups into full flower. Among Jews, the political ideology of Zionism has given birth in the Middle East to a new, specifically Jewish nation-state, continuing to live in conflict with its neighbors but representing a beacon of hope and source of identity for all world Jewry. Among blacks the renewed nationalistic assertions of the Black Power movement of the 60's have now crystallized into a broadly embraced if somewhat nebulously defined Pan-African political identity, inducing blacks to see themselves as a “Third World people,” analogous in their relations with Americans of European descent to the position of the nonwhite peoples of the developing countries vis-à-vis their former European colonizers.

There are interesting parallels in these two developments. In both cases the question arises as to which loyalty—that to the American nation or that to the “tribal homeland”—takes precedence. The question is seldom put so crudely; and often it can be said that the interests of the U.S., properly construed, are wholly compatible with the security interests of Israel, or with the interests of South African blacks in gaining their freedom. But the fact is that, when attempting to influence the policies of our government on matters directly involving Israel or Africa, Jews and blacks act out of motives which go beyond the desire to foster American national interests as they see them. Moreover, how they come to see American interests is, in the long run, surely affected by their ethnic loyalties.

There is nothing necessarily wrong or pernicious in such inevitable conflicts of loyalty—they were observed, for example, among Americans of German and Japanese descent in the years leading to World War II. Sadly, our country has not always exhibited an equal tolerance for such conflict. Self-consciously German Americans were not, after all, rounded up and imprisoned as security threats after war broke out in 1941, while Japanese Americans, the majority of whom were born and raised in this country, were. And many blacks would today claim that their efforts to shape American policy on matters affecting the Third World have met with more questions and a less open reception in the halls of power than have Jewish efforts to lobby on matters affecting Israel.

In any event, the fact is that both blacks and Jews, as American citizens with profound concerns about our foreign involvements, have entered the political arena with the objective of influencing our policy. And this has become a major source of conflict between the groups.

Here, too, the problem has a surface dimension and a deeper, symbolic dimension. On the surface, resentments arise because of disparities in resources, power, and influence between the groups. We sometimes find ourselves on different sides of a policy struggle that only one group can win. A case in point is the Andrew Young affair, in which President Carter's UN Ambassador—the most influential and highest-ranking black ever to have held appointive office in our history, and one whose portfolio explicitly involved foreign-policy concerns—was fired for talking with the PLO in violation of official American policy, and (at least as is widely believed by blacks) at the insistence of American and Israeli Jews.

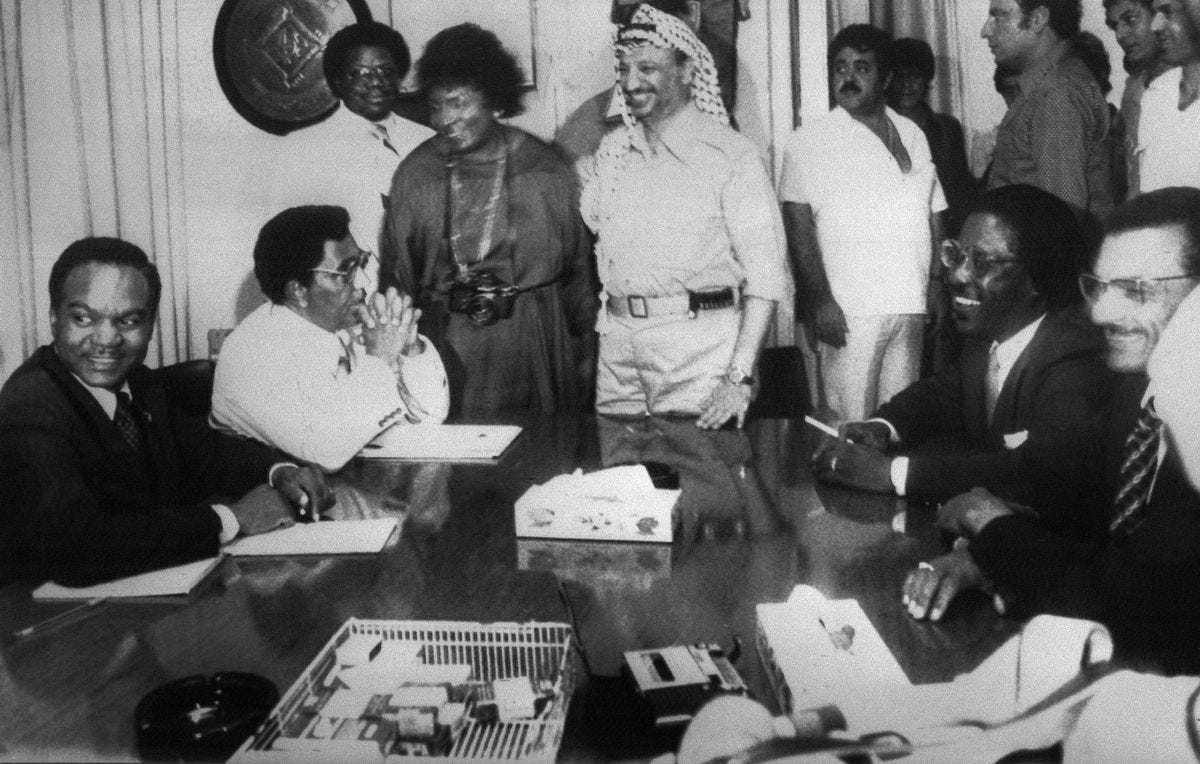

Without doubt this incident can be seen as a proximate cause of the recent deterioration of relations between the groups. Within weeks of the event two separate delegations of prominent black civil-rights leaders made pilgrimages to the Middle East and permitted themselves to be photographed in friendly embrace with Israel's mortal enemies, thus seeming to place the moral authority of the civil-rights struggle—a struggle in which Jewish Americans had figured prominently—at the disposal of Yasir Arafat's PLO. This was, obviously, deeply troubling to many Jews; it disturbed other Americans as well. Even some blacks could be heard to object when Joseph Lowery, head of Dr. Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference and leader of a delegation which included NAACP President Benjamin Hooks and Georgia State Senator Julian Bond, bestowed on the Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi an award of appreciation from American blacks called “The Decoration of Martin Luther King.”

Yet this activity, however much one may disagree with its substance, is probably best understood as an effort by some black Americans to assert their right to participate in the formulation of U.S. foreign policy, an attempt to show that “two can play this game.” Such events do not, in my view, go to the heart of the matter. Rather, this occurrence, and more recent ones of a similar kind, reflect a deeper conflict of vision between the elites of the two groups. With the development of a Third World, pan-national perspective among black elites, such conflict is inevitable, and I fear we will see much more of it. For at base, this emerging political identity among blacks, unlike its counterpart in Zionism among Jews, is profoundly anti-Western. It has been forged from the bitter harvest of frustrated black political aspirations in America. It rejects European intellectual ind economic dominance, regards with serious doubt the most cherished of Western political values, and reflexively embraces anti-Western movements even when they clearly threaten black interests (as evidenced, for example, by the extent of black American support for and identification with the rise of the OPEC oil cartel).

Now Israel, notwithstanding its diverse population, is clearly a creature of the West—historically, culturally, politically, economically, militarily. This is surely one reason why virulent opposition to Israel is almost universal among the nonaligned and Third World nations in the United Nations, and why many black African nations, themselves once dominated and exploited, indeed enslaved, by Arabs, nonetheless reject associations with Israel from which (in the area of agricultural development, for example) they might gain a great deal. There is, therefore, something inexorable about black-Jewish conflict over the Middle East. For much of black elite opinion in this area is shaped by a sense of supranational political identity which, at its core, rejects the very civilization of which the Jewish state is the sole representative in that part of the world.

That black American intellectuals, when reflecting on the question of national identity, would arrive at ambivalent, divided conclusions—at once African and American, partaking of both the East and the West—should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with American history. Indeed, descendants of European Jews might well recognize such an ambivalence from their own past. A central fact of the black experience has been the need to accommodate oneself to the pervasive rejection which, for a century after slavery, was the experience of most blacks in American public life. Perhaps nothing better symbolizes this than the poignant struggles of black soldiers—in engagements from the Civil War to the Korean conflict—to have an equal opportunity to serve and die for the only country they had ever known. W.E.B. Du Bois, in The Souls of Black Folks, wrote lyrically of “this poor dark body, torn asunder” by the conflicting and unresolvable tensions of being nothing else but an American, and yet of never quite being accepted by one's countrymen as an American. Marcus Garvey's back-to-Africa movement struck such a chord among blacks because it seemed to offer a dignified, if utopian, way out of Du Bois's dilemma. And on up to the current day—the appeal of and sympathy for Islam among a devoutly Christian people, the embrace (in some instances the manufacture) of an African cultural heritage which would be unrecognizable to our slave ancestors, the rewriting of world history to discover African antecedents of European accomplishment—all of these are attempts to find an identity for black Americans which is not contingent upon acceptance by whites.

So, in this still developing Pan-African conception of black national identity, blacks are in but not wholly of the West. It is to be expected therefore that their sympathies will lie with what most non-Westerners recognize as the “legitimate aspirations of the Palestinian people” in the Middle East. It does not matter in this that such Pan-Africanism, looked at with detached rationality, may be a deeply flawed ideology, one rejected by many Africans themselves and which, though embraced by black intellectual elites, is foreign to the everyday experience and commonplace aspirations of rank-and-file black people. For it is a perspective which is gaining adherents among the black intelligentsia, and that is what seems to count. And its development is abetted by apartheid abroad, and by black poverty at home.

These are things which Jewish Americans may recognize and understand. Indeed, there are a few similarities here with the early phases of the development of Zionism. But understanding something is not the same as either accepting or changing it. I fear that the conflict among blacks and Jews is not likely soon to abate, notwithstanding the earnest efforts of so many people of good will. For it is the case today that our reflective and influential elites have come to order their experience, as Americans and as citizens of the world, in profoundly different ways.

Glenn, this is a brilliant essay. It took me back in time to those events and ideas that surrounded us in that era. “Comparative Victimology” is a phrase I have been looking for to describe those sorts of discussions. This essay could easily constitute an entire semester of analysis and discussion.

If there are prospects for a better future, we must abandon any attempt to divine a pallet of different remedies that address the uneven real/imagined victimologies. We must recognize the internal contradiction of assuming there can EVER be consensus about adjusting preferential remediations among/between different aggrieved groups. There is no mathematical formula for dealing with real and perceived historical injustices.

The path forward must be premised on a policy that does NOT attempt to apply deferential remedies for some, but not for others. Affirmative discrimination can never be applied in such a manner that differential levels will satisfy everyone. It's a fool's errand to assume otherwise. Equality of opportunity and equality before the law are the only principles that can unite disparate identities for the common good.