In this clip from Glenn and John’s most recent subscriber-only Q&A session, they discuss when it’s acceptable to apply statistical information and lived experience about racial disparities in violent behavior to real-life situations. Knowing that young black men in urban areas commit violent crimes in disproportionate numbers, are we justified in regarding all young black men as potential threats? Or does is that mere racial stereotyping that leads us to treat individuals in an unjust way?

This clip is taken from a subscriber-only Q&A session. For access to Q&As, comments, early episodes, and a host of other benefits, click below and subscribe.

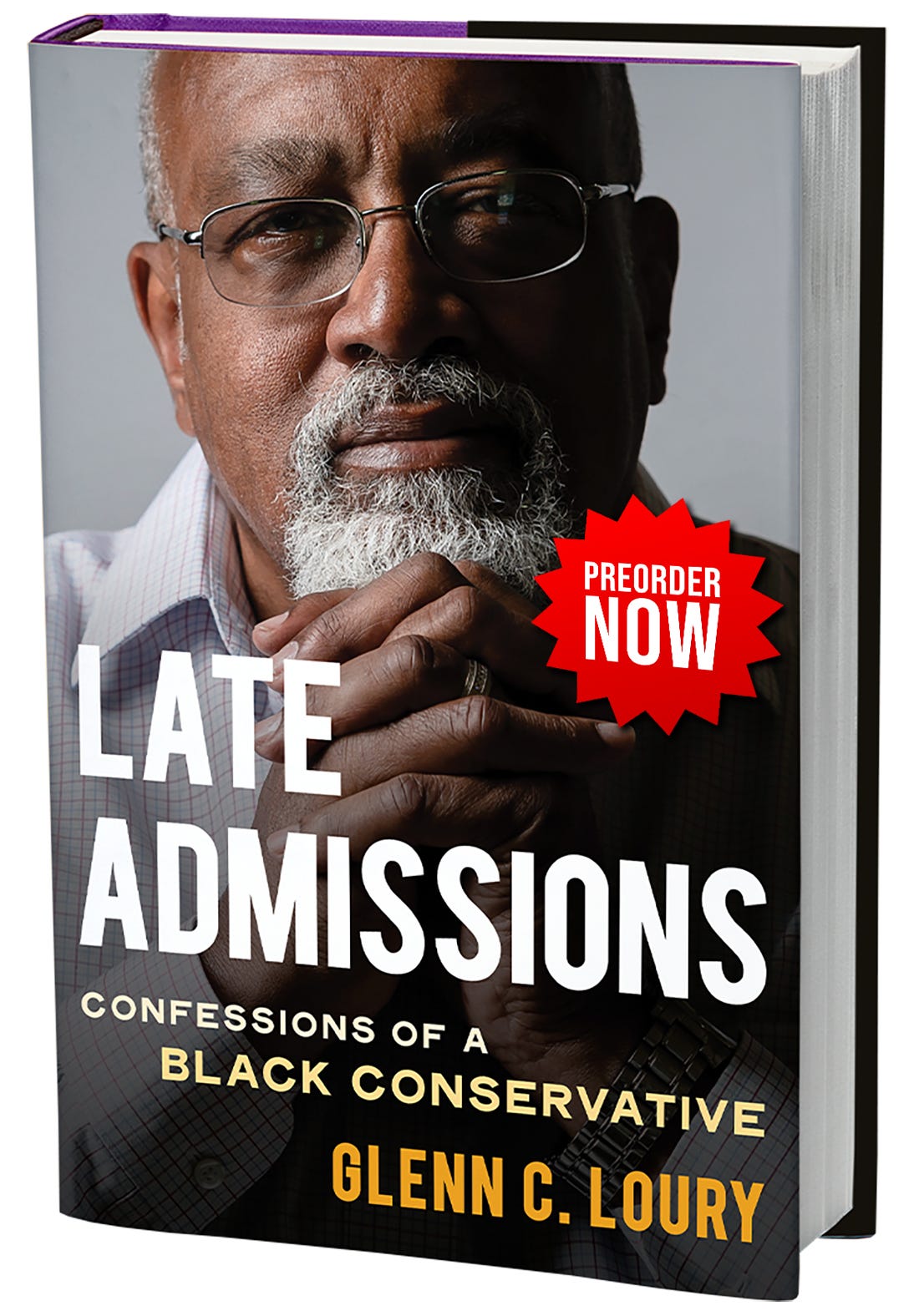

GLENN LOURY: This is William.

On the general topic of racism, is it ever acceptable to apply general stats regarding violent crime among and between the races to our personal lives? For example, I believe you both have expressed that due to the current crime rates, it's perfectly rational to fear groups of young black men in downtown Chicago. And if that is acceptable, then when is the application of stats not acceptable? How would you define a truly racist act or belief?

Okay, I'll start off in responding to that question by saying, yes, it is sometimes acceptable to apply general stats regarding violent crime between and among the races to our personal lives. That's simply common sense. If I know that the offending population in a particular city at a particular point in time is vastly disproportionately black, and I see a group of black youngsters at 1:00 a.m. when I've come out of the club and I'm staggering to my car, and I see a group of white youngsters, and I regard the first as more menacing than the second, that's a protective inference that I'm making that I don't see how you could possibly regard as a morally inappropriate reflex.

And yes, it is a stereotype. Yes, stereotyping is a part of social life. We all do it in one circumstance or another. The fact that it's based upon race, it shouldn't be the end of my inquiry. I should pay attention to other facts about the situation that I'm attending to. But to ignore the racial disparity in the background, it seems to me, is asking way too much.

Now, is it asking too much of a police officer that he override the instinctual reflex to take on board racial statistics when he's deciding who to stop for a traffic violation? What about a professor who knows that the Asian kids in his classroom have gotten very high grades in the past? Should he pay more attention to the Asian kid’s question or give a greater latitude to the paper that he's grading that comes in from an Asian kid? Of course not. That would be, in my view, violative of basic principles.

But to tell me that I don't cross the street? Again, race is not the only thing, but race would be a part of it. To tell me that I don't cross the street when I feel threatened, I shouldn't feel threatened, I think that's asking way too much of people. I think the instinct to do that is deeply ingrained in our social behavior because that kind of information can be very valuable and make the difference of life and death in certain situations. And no, I don't believe it's racist to be afraid of a group of black teenagers on the streets of downtown Chicago at 11:00 p.m. No, I don't think that's crazy or racist, for that matter.

The question is, if they were white, would I not be afraid? And the answer is, in my case, probably I would not be as afraid. I'm going to just acknowledge that.

JOHN MCWHORTER: I agree with everything you said. I would just add that all of that is fact that cannot be escaped and a kind of stereotyping that must be pardoned. Because it's stereotyping, sometimes it is going to go wrong. Sometimes you are going to have a generalization that's going to turn out to be all wrong because stereotypes may have a basis in fact, but still they are stereotypes. That is a tough one.

And so for example, I'll openly admit: New York City. This is my city now for 22 years, and the subway is a fascinating place to observe all sorts of things going on, including how race lays out. And I've been riding that train most days of my life, for now a quarter century.

I would say that when somebody busts into the car from one end, which you're not supposed to do, but if somebody busts in, if I look up wondering who that person is and what might be coming, I will openly admit that if the person coming is some white guy—which it almost never is—then my thought is, whatever. He's desperate for a seat. If it's a black guy, there's a part of me that thinks, is the black guy going to be asking for money? Is the black guy going to start break dancing and accidentally maybe kick somebody in the head and say menacing things to the people in the car along the lines of “we need your positive energy,” but practically saying it with a frown, as if setting themselves up as adversaries of society who we owe money and attention? Frankly, that's a routine that the black break dancer guys do.

Now, often, it's a black guy who's just like the hypothetical white one. He just wants a seat. But I must admit that when they come, and especially if it's two, there's a part of me that thinks what's it going to be or is this person going to start yelling at people or something like that. Because the sad truth is—I'm sure it's happened, but I'm part of the statistics—I've never encountered a white guy on the New York subway yelling in people's faces and making people that uncomfortable. And I've certainly never encountered an Asian one or a South Asian one. A Latino one, occasionally. I'm probably forgetting one time, but that is the black guy.

Now there are reasons for that, sure. You're not gonna tell me I'm stereotyping. It's just fact, based on a quarter-century of living the life. So yeah, it's inevitable. That's just the way it goes.

I think there's an important implication of what you just said. That is, it's almost never a white guy who's the crazed person bursting into the car, threatening and so forth and so on. That's not to say that most black people do it. No, those are two different statements. It could be that very few black people do it.

But if it's almost never a white guy who does it in New York City subway—let me just stipulate that's a fact. I don't know the New York City subway, but okay, it sounds right to me—then when a white guy comes through there and you're not afraid, that's just the rational response to the situation. When a black guy comes through, it may be one in ten that he's actually a bad actor. But one in ten is a pretty high number if the bad actor's got a knife.

And the funny thing is, one time—talk about people who fall outside of your expectations—one time somebody comes breaking into the car, and this guy's an orator. Maybe he's on something, but he's an orator who thinks he's got political wisdom. It's a black guy, young black guy. And one of the things he said was, “And Charles Murray can kiss my ass!” It was a very well-read thug orator. He was just expecting everybody to know who that was. So that kind of went against the stereotype. But still, I wish she had not been yelling and screaming and making people uncomfortable.

Do you feel safe on the subway with your girls in New York City?

No, I don't. It's not as bad as it was about a year ago. That has to be acknowledged. But I worry. There's almost always somebody in the car if you stay in there long enough. It's not that I don't feel safe. It's not like there are people down there regularly shooting guns, et cetera. That makes the news. I've never seen a shooting. Watch it happen tomorrow.

But what you get is people who are angry and crazy. They're not happy crazy, they're angry crazy. And unfortunately, it's almost always a black guy. So if we're in the car and there's somebody who's laying out, stretched, sleeping on a seat and the other cars are full and you sit down, I worry. Because those guys tend not to stay asleep long. They wake up and they want to raise some hell.

It's the only way they have of having contact with people. I get it. I can imagine how they feel. But I don't like that my girls are growing up and they're seeing only black men doing that. And I can try to correct it, but—talk about stereotyping—they're not going to be able to help stereotyping based on what they see.

It's not a white guy who's waking up and screaming. Or if it is, it's much, much less often. The truth is, and I don't know what the answer to this is, the white guy is not confronting people and usually isn't angry. That's the thing. It's the black guy who wakes up, starts yelling. And maybe it's just general black pain, et cetera. But in terms of day-to-day experience, it's not something I like my girls seeing. It's hard. And that person is never Asian.

Stereotypes are part of our survival mechanism. They inform our fight or flight impulse, among other things. Stereotypes are true of the group in question regardless of the identity of the group. They are not useful in assessing an individual. We should understand how stereotypes works and when they don't, but never apologize for them.

I worked as a taxi driver in Downtown Los Angeles many years ago. During that time, it was a common grievance among several Black entertainers that taxis often bypassed them. This concern was indeed grounded in reality. Many drivers, myself included, wouldn't stop for young Black men. This caution was not limited to any driver of any race; even Black taxi drivers were similarly cautious.

The reasoning behind this caution was statistically driven: 85% of reported cab robberies at the time involved young Black and Latino men. However, this statistic does not reflect the majority of young Black men who were simply going about their daily lives, seeking a ride to get home or to their workplace.

Reflecting on this issue, it's clear that the solution isn't just for drivers to disregard their safety concerns. A more effective approach would be to address the root socio-economic factors that contribute to higher crime rates among young Black men.