Throughout the process of writing Late Admissions, I kept wondering how my children would respond to it. My relationship with them was not always easy, and much of that difficulty had to do with choices I made. Going back through my own life and examining it as closely as I could, forcing myself to look squarely at my decisions, I kept wondering, “My God, what will Lisa and Tamara think of what I was up to? What will Alden think? What will Glenn II and Nehemiah think?” Their lives were sometimes harder than they had to be because of my actions. Would reading about it all reopen old wounds or help them to heal?

I didn’t want to wonder anymore, so I invited my son Glenn II on the show to talk with me about the memoir. The result is a conversation unlike any I have ever had on-camera and like few I’ve had off-camera. You’ll see the two of us negotiating a minefield of painful memories, misunderstandings, and delicate subjects to try to meet each other in the middle. We discuss the difficult years of our relationship, my treatment of my second wife, Glenn II’s mother, Linda Datcher Loury, and both Glenn II and my alienation from my father, Everett. I knew my son had a complicated response to the book—how could he not? But I wanted to know if it helped him understand who I was, who I am, and how I have changed.

In this clip from this week’s episode, Glenn II describes how, by working through his own feelings and seeing mine exposed, he came to empathize with the flawed individual I describe in Late Admissions. I’m awed by the capacity for grace and the penetrating insight he offers in this conversation. I’ll be forever grateful that it’s recorded for posterity.

This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

GLENN LOURY II: Your life story in and of itself, it's a series of hills, climbing and descending, going up and down, coming so close to the mountain top and throwing yourself off. And it would be easy for people to judge you and say, “Why would you do that? You were so close. Why did you fuck things up for yourself?”

I'm sorry. Can I swear here?

And I think it's easy for people to judge you for doing so. I know I did. But as you become an adult, you realize that the people that raised you had no choice but to be who they were, and to be angry at them for that and to judge them for that is the easy choice. It's easy to shake your finger at somebody and say that you should have made better choices. You should have been better, but nobody can be but what they are. And who you are is both a brilliant mind that is—that was, I think—helplessly bound by its own frailties and insecurities to make poor choices. And it took a long time to overcome that, and you were fortunate to have the opportunity to have that time. Most people are not that lucky.

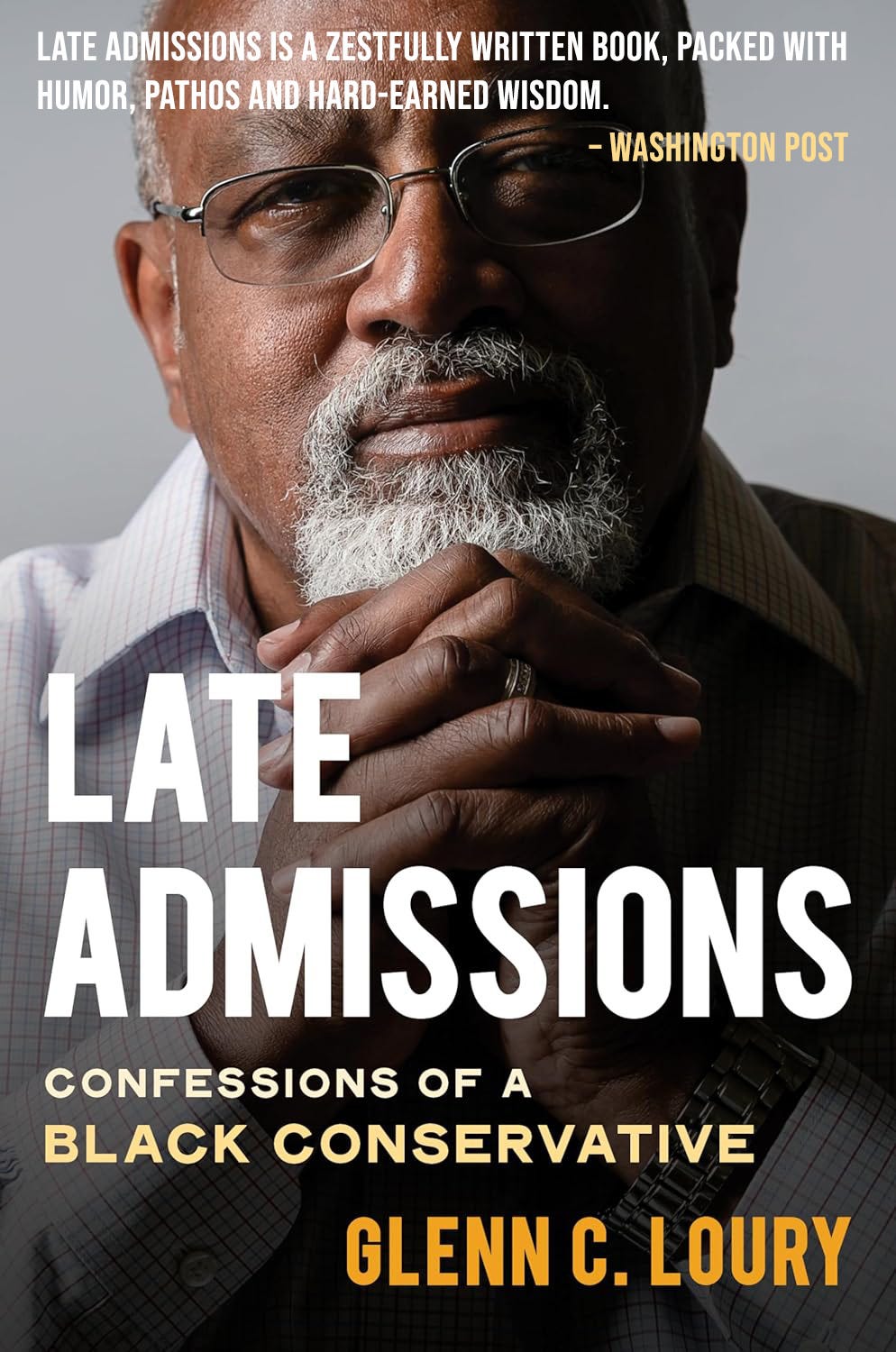

GLENN LOURY: Yeah. I wanted to just say, without in any way trying to rebut what you've just said, which I think is absolutely correct, I wanted to say that it's a long life and the privilege extends in my case to being granted time to reflect. And Late Admissions, my memoir, is the fruit of a decade's worth of reflection, maybe even more.

That process of honestly, candidly, self-critically engaging in the reflection, while it can't cancel the error, might have some redeeming feature to it. Certainly, that's my hope. And this will be a little self-flattering. I wonder what you think about this: that in telling it and laying it all out, people have asked me, “Why would you be so candid? Why would you tell that? Why wouldn't you tell that? And, oh, you come off not looking so great here. You come off not being such a likable person here.”

And I want to say, as they used to say when I was going to church, God's not finished with me yet. Which is to say, it's an unfolding account here. With the benefit of living well into my eighth decade and having survived stuff that would have taken a lot of people out and probably should have taken me out, I certainly, by the grace of whomever, by God, or the loving wife who stuck by me—your mother—or just good fortune, friends, a socioeconomic location that allowed me, the benefits of good insurance policies and pliant and cooperative employers who gave me a second chance, third chance. But here I am and I can tell the account. I can tell the account honestly, and I can peel back the different layers of-self justification. And I can, perhaps, can I not, contribute to the greater good in this way, even as I exhibit, warts and all, the circumstances under which I failed to fully live up to what it is that I would nevertheless want to affirm to be righteous and dignified living.

I don't know. That's my gambit. That's what I'm hoping a sympathetic reader, my son, would come away from this book with.

Let me answer your question by reflecting on my childhood a little bit. I remember growing up, meeting fans of yours or colleagues or students or people who just knew who you were out in the world when I was a young adult. Going to college with your name, inevitably people would say, “Oh, are you related to the Glenn Loury?” Which was frustrating for me. And answering that question, honestly, I think sometimes I wouldn't. I often took people by surprise because I think people universally expect me to say, “Oh, it was great.”

I think it would be fair, and I don't think you would disagree with me, [to] characteriz[e] our relationship in my teenage and adolescent years as challenged. There was a lot of conflict, there was a lot of antagonism both ways. Because I think you put on a good show. I think you present yourself very well to people who don't know you. And I think that's part of why this book took a lot of people by surprise.

The Glenn Cartman Loury Sr. who raised me could not have written this book. He would not have been capable of the self-reflection, the honesty, or the vulnerability that was necessary to write this book. So I am proud of the man that you've become. Everybody grows. Even people who live long enough to have the opportunity to, many of them don't change. And you have.

So reading this book, it was an interesting experience for me. I found myself getting angry at somebody who I don't really think exists anymore. I've gone to therapy for a lot of my life. One of the things that I had to learn is that anger is an emotion and it's legitimate and you have to feel it and you have to process it. But it's also not something that's necessarily useful to hang onto. Because for a lot of my life, I'm like, he's just never going to understand why. And if he's never going to understand why, you have to just process it yourself and then deal with that and be okay with it.

I have come to an unexpected place where you have done this work of self-confession that I think has caused you to maybe face a lot of things. This wasn't an easy book to write. It wasn't an easy book to read, but it must've been a much harder book to write. Because you're going through your past and you are naming the ... You're not a Catholic, but this is you basically going into the confession booth—except the whole world is your priest—and listing out all of your sins.

And I do think there's a value in that. Maybe just for me we'll see how the American public consumes it. But I think there's a value in showing people that success is not what makes you happy or fulfilled. What is success? I don't think you knew what that was when you were coming up as a young man, when you were trying to define yourself politically. I don't think you knew what you wanted. I think you had a gift. I think it opened some doors for you. And I think when you got through those doors, you weren't happy that people weren't as happy to see you as you thought they should be, and that you made some choices and reactions to that that defined you in ways that you weren't expecting. So you had to recalculate and recalibrate, and you made mistakes.

But you kept trying, and that's a reflection of not just who you are personally, but politically, to go back to the conservatives. Like you made mistakes, you have positions that I don't believe in, but you keep listening. I think that only happens if underneath those mistakes, those poor choices, those scars that you suffered emotionally, that there is a beating heart that really just is looking for people to love him in the way that he thinks that he should be loved and maybe didn't necessarily get that in the way that he was looking for when he was younger. And as somebody who knows what that's like, I empathize, as an adult, with that man.

That's very moving, Glenn. That really warms my heart to hear. And I want to say to all the world that I love you, my son, Glenn Carman Loury II, born January 3rd, 1989. Ah, maybe I shouldn't have told that. I'm sorry I revealed your age.

As long as it's less than yours, I'm not complaining.

And his mother, Dr. Linda Datcher Loury, my wife of 28 years, my best friend of 37 years.

I listened to part of the conversation and just now watched it. Listeners need to watch this to see Glenn II's face when he speaks to his dad. Missing that, one misses the warmth between father and son and the gentleness evident with both. A beautiful conversation.

Thank you both for sharing this conversation.