According to my friend Rajiv Sethi, there is some real antisemitism on campus at Columbia and Barnard, but very little. The vast majority of students and faculty aren’t antisemitic at all. That squares with my experience of comparable college campuses, including Brown. But a handful of incidents have gained outsized importance in the public discourse around the Trump administration’s crackdown on Columbia. A casual observer could be forgiven for thinking New York’s Morningside Heights is infested with antisemites, which would come as a surprise to those who live and work there.

So are we letting the tail wag the dog, here? I take Rajiv’s point that the Star of David is not just an emblem on the Israeli national flag. It’s a symbol that represents the Jewish religion as well. One could easily and fairly interpret an image of a boot crushing a Star of David as an expression of antisemitism, not merely as a protest against the actions of a state.

But if, as Rajiv says, expressions of genuine antisemitism are rare, they shouldn’t determine the parameters of free speech. I’m troubled by the idea of anyone—university administrations as well as federal agencies—issuing edicts about what can and can’t be said, what images can and can’t be displayed. Even if the intent is to constrain antisemitism, such edicts will inevitably chill speech. Students and professors will ask themselves whether displaying these images and repeating these ideas, even for legitimate educational and scholarly purposes, will get them in trouble with the administration or make them into targets for overzealous supporters of Israel.

That concern doesn’t apply to, say, masked protestors storming into a class about modern Israel and distributing flyers that any Jews in the room would reasonably interpret as a threat. A threat isn’t protected speech. But odious utterances and images don’t qualify as threats merely because we find them repugnant or offensive.

As Rajiv says, the First Amendment is good for us. It’s good for us not despite its protection of offensive speech but because of that protection. That’s easy to agree with in principle and hard to deal with when confronting actual offensive speech. Our impulses might urge us to shout down a speaker we regard as unacceptably extreme or hateful. But that’s why we need the First Amendment—we sometimes need to constrain our own censorious impulses as well as the government’s. The First Amendment is not merely a legal statute. It’s a democratic value, possibly the core democratic value. If we abandon it in order to win isolated political battles, we’ll end up losing the war.

This is a clip from an episode that went out to full subscribers earlier this week. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

GLENN LOURY: How bad is the antisemitism problem at Barnard-Columbia, in your opinion?

RAJIV SETHI: I think that most people—students, faculty—are not antisemitic in the slightest. That's my view. But there have been incidents that are quite clearly antisemitic. And the one that I mentioned in my post from this morning is the interruption of a class on the history of modern Israel early in the semester, the first week of classes, where a group of students disrupted a class and circulated flyers.

And those flyers actually were quite grotesque. They involved violent imagery of boots stomping on the Star of David, the Israeli flag burning, and various statements that accrued and that I won't repeat here. So you have examples of these. And of course, given the social media landscape we live in, they get amplified and distributed. And so my answer to your question is there are actually very distressing, very grotesque examples of antisemitism. But they are rare, in my opinion.

And those people who are not part of the community view these things with disproportionate frequency. They're not really witnessing the day-to-day activities of faculty and students, which have nothing to do with that. And so they take an outsized place in the imagination of those who are forming opinions about Columbia and about Barnard and about higher education in general.

So I would say there are plenty of examples of it. But I would say that perceptions of its presence in the country at large is possibly out-of proportion with its prevalence.

Lemme play the devil's advocate here for a minute. Supposing the US invades Iraq in 2003, and I don't like it. I go on campus and I have a rally and I burn an American flag, and I say “The empire—it's fascist, militaristic,” whatever. What would happen to me? Nothing. I'm protected by explicit Supreme Court rulings that burning an American flag is not a punishable offense, that it's an expression of sentiment.

But if I burn an Israeli flag and I upset my Jewish student and faculty members of my community because it intimidates them, it makes it seem as if I'm anti-Zionist, I'm pro-Hamas? That's gonna be enjoined? How can that be justified?

I take your point. Let me distinguish between the flag burning and the boots stomping on the Star of David. The Star of David is not a symbol that is exclusively associated with Israel. It's associated with the religion.

Fair point.

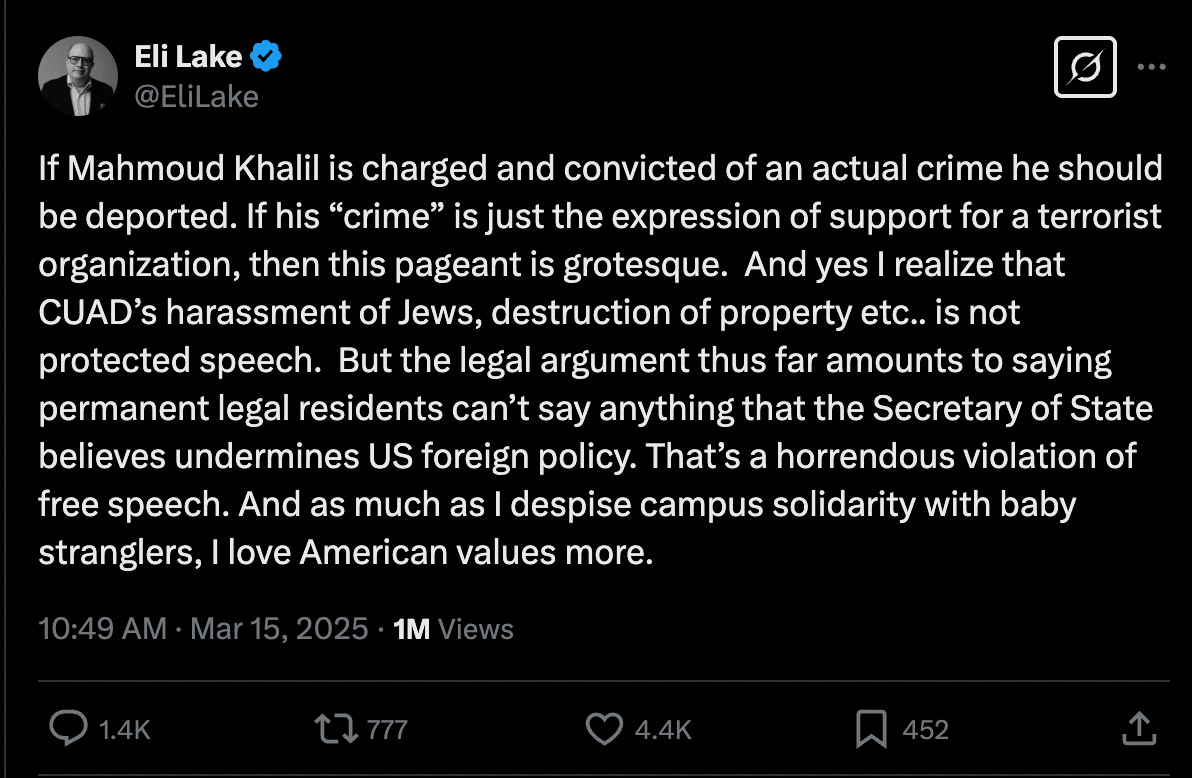

I think it more reasonable to describe that as being quite clearly antisemitic. It seems like it to me. But your point is well-taken. This is addressed squarely by Eli Lake's tweet.

He considers Khalil to be an apologist for a terrorist group. And despite that, he thinks that, unless he's committed a crime, he ought not to be deported, he ought to have due process, and the speech alone, even support for a terrorist organization, does not warrant this kind of treatment. The fact that he happens to be a Green Card holder rather than an American citizen is not really relevant to our judgment of this fact.

I think this is an important point. We should think about why we have and we value the First Amendment. I think there's two ways to look at it. One way is to say, look, American citizens have certain rights. This is one of them. People who are not citizens, who may be visiting the country, don't have those rights. And so it's okay to treat people differently based on citizenship status.

We have the First Amendment because it's good for us, because the freewheeling debate that it encourages, the ability to voice the most extreme positions, can actually be instructive, can teach us something. Engaging with those views can help us understand our own views, and so on. The arguments are very familiar.

If the reason that we have and we value the First Amendment is because it does something very good for us, even when we have to listen to some things that are deeply unpleasant, then whether or not someone is a citizen becomes irrelevant. Anybody who's making a statement that has political valence and that challenges us to think about our own preconceptions has value.

And that's a very different way to think about free speech, in my opinion. That's the view that Lake is advancing. He absolutely detests the speech. But if one takes the point of view that it's part of the American tradition because it's good for America, then the citizenship status becomes irrelevant. And that's my position.

I was under the impression that the protections of the Bill of Rights did apply universally. Residents in the United States, regardless of their citizenship—“Congress shall make no law” is a prohibition against making a law that would bear on anybody, not only citizens.

That's true, Glenn. But there's also an act of Congress that allows for the deportation of Green Card holders if the Secretary of State were to decide that some of their speech or actions are contrary to US foreign policy interests.

That ought to be unconstitutional based on the argument that you just made, but it hasn't been found to be. So that law is on the books. Marco Rubio, as Secretary of State, can decide that somebody has said something that is contrary to US foreign policy interest, and the law allows him to deport them, even if they're a Green Card holder.

There are conflicting statutes here. And I think it has to be resolved. I think actually it's a very good thing that the courts are looking at it.

After "Black Power", one of Stokely Carmichael's favorite slogans circa 1970 was "The Only Good Zionist is a Dead Zionist". At the time Carmichael had decamped to Guinea-Bissau, a military dictatorship backed by the USSR. The USSR was also the main military backer of Nasser and the Pan Arab movement, that suffered a massive defeat in the 1967 war. To get back at Israel the USSR launched a large propaganda campaign. All the tropes we hear on University campuses today -- Zionism=Oppression=Racism=Facism=Imperialism=Apartheid -- were part of this campaign. Much of the Soviet literature reads like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion except with the word Zionist substituted for Jew. The USSR pumped this propaganda through all of its leftwing channels -- the European Communist Parties, CPUSA (e.g. Angela Davis), Indian and Asian Communist Parties, etc. Read Izabella Tabarovsky's article on this https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/zombie-anti-zionism. The Anti-Zionist dogma has been a standard component of the left since this time, and the leftwing professors in the X-Studies departments of American Universities inherited this. The USSR propaganda always insisted that Anti-Zionism is not the same as Anti-Semitism. Even so, the policies they implemented after 1967 included forbidding Soviet Jews from entering certain professions and Universities proving that, in fact, much of Anti-Zionism is, in fact, Anti-Semitism. This is why the adoption of the IHRA definition of Anti-Semitism which calls out certain types of Anti-Zionsim as Anti-Semitism is important. The leftwing professors today are the students of the students of anti-Vietnam war activists, radical feminists, Black Panthers who went into Academia in the 60's and 70's. The professors today are probably themselves unaware of this history. Understanding this 60 year history is essential to understanding the obsessive focus on Anti-Zionism in Universities today.

Way to have two non-Jews declare not much antisemitism at Columbia where Muslims openly harass Jews.