Last week, I posted a clip in which John and I discuss our “origin story.” We’ve been talking on mic for almost 18 years now, but our relationship actually predates The Glenn Show. Our first substantial public exchange occurred in the pages of First Things magazine in 2002. The editors there assembled a forum about my then-new book The Anatomy of Racial Inequality. Both John and the philosopher Jorge Garcia wrote long, substantive, critical responses, and I replied to them.

Jorge I knew well. He was at that time a fellow at the Institute on Race and Social Division at Boston University, which I created and ran. I expected nothing less from him than a deeply considered, philosophically adroit critique—in fact, I would have been disappointed if he had held back. I took the intellectual seriousness of his piece, critical though it was, as a sign of respect from a thinker I admired.

John I didn’t know well. He was just getting his start as a public intellectual, and I didn’t yet know where he was coming from. So when I read his deeply considered critique, I took a little bit of offense, and you can see it in my reply to him. John and Jorge’s pieces are available at First Things’s website, but my response is cut off. With the help of the magazine’s current editorial team, I tracked down a copy, and I’m posting it below. Today, it’s a little surprising to revisit my own vociferous rejoinder to John—my tone is hardly collegial. If you had told me in 2002 that he and I would be friends and close collaborators over twenty years later, I wouldn’t have believed it. And yet, here we are.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

In The Anatomy of Racial Inequality I aim to do three things: outline a theory of race applicable to the social and historical circumstances of the United States; sketch an account of why racial inequality in our society is so stubbornly persistent; and offer a conceptual framework for the practice of social criticism on race-related issues that might encourage reflection among our political and intellectual elite, and in this way promote social reform. These objectives are subsumed, respectively, in successive chapters of my book entitled “Racial Stereotypes,” “Racial Stigma,” and “Racial Justice.” Jorge Garcia takes issue with me at every step of this program. Although I am convinced that he is wrong and I am right about the points in contention, I am profoundly grateful to Professor Garcia for his close reading of, and intellectually serious engagement with, my text.

Any theory of race, it seems to me, must explain the fact that people take note of and assign significance to superficial markings on the bodies of other human beings—their skin color, hair texture, facial bone structure and so forth. This practice is virtually universal in human societies. Scientists have conjectured that it has a deep neurological foundation. So this is the point of departure for my analysis. I refer to a society as being “raced” when its members routinely partition the field of human subjects whom they encounter in that society into groups, and when this sorting convention is based on the subjects' possession of some cluster of observable bodily marks. This leads to my claim that, at bottom, “race” is all about “embodied social signification.”

Let us call this the social-cognitive approach to thinking about race. It may be usefully contrasted with an approach derived from the science/art of biological taxonomy. There one endeavors to classify human beings on the basis of natural variation in genetic endowments across geographically isolated sub-populations. Such isolation was a feature of the human condition until quite recently (on an evolutionary time scale), and it permitted some independence of biological development within sub-populations that can be thought to have led to the emergence of distinct races. When philosophers such as Jorge Garcia or Anthony Appiah deny the reality of “race” they have in mind this biological-taxonomic notion, and what they deny is that meaningful distinctions among contemporary human subgroups can be derived in this way. Whether they are right or not would appear to be a scientific question.1 But, whatever the merits of this dispute, it is important to understand that the validity of racial classification as an exercise in biological taxonomy is conceptually distinct from the validity (and relevance) of my concern with racial categorization as an exercise in social-cognition.

Moreover, and this too is absolutely critical, to establish the scientific invalidity of racial taxonomy demonstrates neither the irrationality nor the immorality of adhering to a social convention of racial classification. We can adopt the linguistic convention that when saying, “person A belongs to race X” what we mean is that “person A possesses physical traits which (in a given society, at a fixed point in history, under the conventions of racial classification extant there and then) will cause him to be classified (by a preponderance of those he encounters in that society and/or by himself) as belonging to race X.” This is a pragmatic judgment on my part, not an a priori logical claim. That is, I hold this view because the social convention of thinking about other people and about ourselves as belonging to different races is such a longstanding and deeply ingrained one in our political culture that it has taken on a life of its own. Thus, for students of the history and political economy of the modern multiracial nation-state like me, the logical exercise of deconstructing racial categories by trying to show that nothing “real” lies behind them is largely beside the point.

This point of view is supported by the theory of “self-confirming stereotypes” that I advance in the book. My point here is a subtle one, and I am not sure that Garcia grasps it. Imagine people who believe that fluctuations of the stock market can be predicted by changes in sunspot activity. They might do so because, as an objective meteorological matter, sunspots correlate with rainfall, which influences crop yields, thus affecting the economy. Or, solar radiation might somehow influence the human psyche so as to alter how people behave in securities markets. These are objective causal links between sunspots and stock prices. They can be likened to grounding one's cognizance of race on the validity of a race-based biological taxonomy. But suppose that no objective links of this kind between sunspots and stock prices exist. Even so, if enough people believe in the connection, monitor conditions on the sun's surface, and act based on how they anticipate security prices will be affected, then a real link between these evidently disparate phenomena will have been forged out of the subjective perceptions of stock market participants. That is, belief in the financial relevance of sunspot activity will have been rendered entirely rational.

Similarly, no objective racial taxonomy need be valid for the subjective use of racial classifications to become warranted. It is enough that influential social actors hold schemes of racial classification in their minds and act on those schemes. Their methods of classification may be mutually inconsistent, and they may be unable to give a cogent justification for adopting their schemes. But once a person knows that others in society will classify him on the basis of certain markers, and should these acts of classification affect his material or psychological well-being, then it will be a rational cognitive stance—not a belief in magic and certainly not a moral error—for him to think of himself as being “raced.” In turn, that he thinks of him- self in this way, and that his societal peers are inclined to classify him similarly, can provide a compelling reason for a newcomer to the society to adopt this ongoing scheme of racial classification. Learning the extant “language” of embodied social signification is a first step toward assimilation of the foreigner, or the newborn, into any “raced” society.

I thus conclude that races, in the social-cognitive sense, may come to exist and be reproduced over the generations in a society, even though there may exist no races in the biological-taxonomic sense. So while I accept Garcia's point that calling attention to the social practice of racial classification cannot resolve a scientific dispute on the existence of races, I continue to insist that, for the purpose of understanding how race operates in the American social hierarchy, my “embodied social signification” viewpoint is both logically coherent and analytically useful.

I suspect the foregoing will not convince Garcia, and I think I know why. He is an ethicist, keen to move from the cognitive to a normative discourse. He wants to say, I infer from his argument here, that there is something “wrong” with seeing others (or, for that matter, oneself) in racial terms—with preferring to associate with people because of their racial identities, with feeling obligated to co-racialists, and so on. Just as one might think it wrong to punish people (witches) for the crime of being “the devil's handmaiden” when in point of fact no people actually are, so too one might think it wrong to condition one's dealings with others on the basis of “race” when, in point of fact, there are no (biological-taxonomic) “races.” If there are no races, then what possible justification can there be for the embrace of racial identity? My view is that the existence of races (in the biological-taxonomic sense) and the ethics of the practice of racial classification are largely distinct problems. What is more, I do not think we can get at the latter problem by interrogating the human heart, one person at a time. It is a mistake, in my view, to judge the propriety of social conventions in terms of whether individuals behave virtuously or viciously when they elect to comply with those conventions. To be taken seriously, an ethical critique of race-based thinking must get beneath (or behind) the cognitive acts of individual persons and investigate the structure of social relations within which those individuals operate.

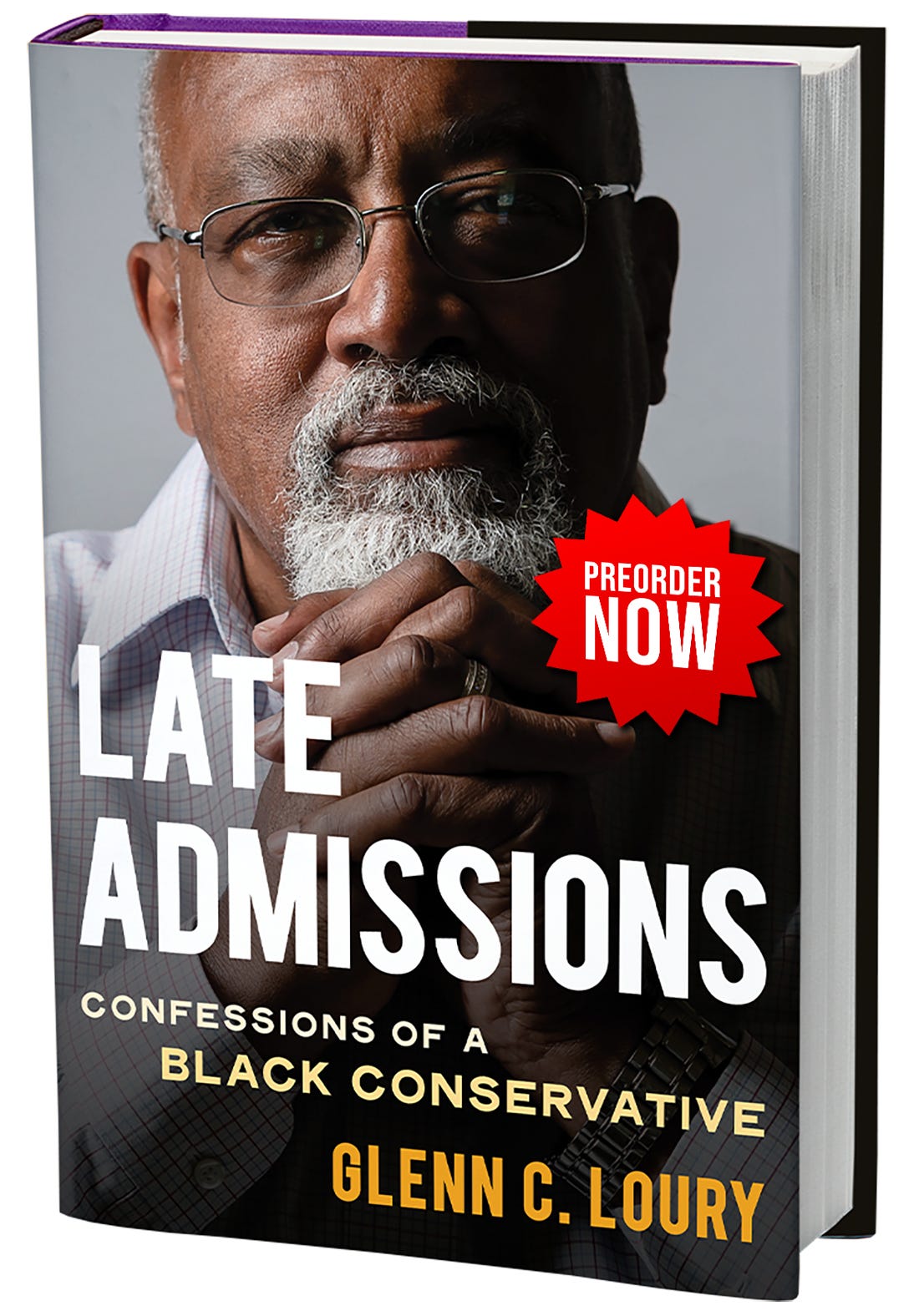

Glenn’s memoir, Late Admissions: Confession of a Black Conservative is coming out in mere days. Order your copy now from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, or wherever you get your books!

This brings me to the topic of racial stigma-the central innovative concept in my book. Garcia charges that I am unclear about my meaning here, and John McWhorter sees me as reiterating, in a slightly modified form, the tired liberal charge that blacks do not succeed because whites are guilty of moral malfeasance. Both charges are groundless. To reiterate, my basic approach to the problem of racial inequality is cognitive, not normative. I eschew use of the word “racism” not to avoid sounding like an outdated civil rights leader, but because the word is imprecise. More useful, I think, is my core concept—“biased social cognition.” McWhorter certainly, and Garcia to a lesser extent, misunderstand my intent here. Racial stigma is not a bludgeon with which I hope to beat “whitey” into political submission. It does not refer to “sinister” thoughts in the heads of white people. Nor is it an invitation to passivity for blacks. Rather, what I am doing with this concept is trying to move from the fact that people take note of racial classification in the course of their interactions with one another to some understanding of how this affects their perceptions of the phenomena they observe in the social world around them, and how it shapes their expla- nations of those phenomena.

Given the evident sensitivity of racial discourse, it is perhaps best if I make the point with a nonracial example. So consider gender inequality, disparity in social outcomes for boys and girls, in two different venues—schools and jails. Suppose that, when compared to girls, boys are overrepresented among those doing well in math and science in the schools, and also among those doing poorly in society at large by ending up in jail. There is some evidence to support both suppositions, but only the first is widely perceived to be a problem for public policy. Why? My answer is that it offends our basic intuition about the propriety of underlying social processes that boys and girls do differentially well in the technical curriculum. Although we may not be able to put our fingers on exactly why this outcome occurs, we instinctively know that it is not right. In the face of the disparity we are inclined to interrogate our institutions—to search the record of our social practice and examine myriad possibilities in order to see where things might have gone wrong. Our baseline expectation is that equality should prevail here. Our moral sensibility is offended when it does not. And so, an impetus to reform is spurred. We cannot easily envision a wholly legitimate sequence of events that would produce the disparity, so we set ourselves the task of solving a problem.

Gender disparity in rates of imprisonment, on the other hand, occasions no such disquiet. This is because, tacitly if not explicitly, we are “gender essentialists.” That is, we think boys and girls are different in some ways relevant to explaining the disparity—different either in their biological natures, or in their deeply ingrained socializations. (Note that the essentialism with which I am concerned need not be based solely or even mainly in biology. It can be grounded in [possibly false] beliefs about profound cultural difference as well.) As gender essentialists, our intuitions are not offended by the fact of vastly higher rates of imprisonment among males than females. We seldom ask any deeper questions about why this disparity has come about. And so we see no problem.

Now, we may be right or wrong to act as we do in these gender disparity matters. My point is simply that the bare facts of gender disparity do not, in themselves, suggest any course of action. To act, we must marry the facts to some model of social causation. This model need not be explicit in our minds. It can and usually will lurk beneath the surface of our conscious reflections. Still, it is the facts plus the model that lead us to perceive, or not perceive, a given circumstance as indicative of some as yet undiagnosed failing in our social interactions. This kind of reflection on the deeper structure of our social-cognitive processes as they bear on the issues of racial disparity is what I had hoped to encourage with my discussion of “biased social cognition.” And the role of race in such processes is what I am alluding to when I talk about “racial stigma.”

To show how the argument goes, I would like to invoke a thought experiment not unlike the ones I analyze at length in my book. For some reason, McWhorter thinks that these are “anecdotes,” and he accuses me of playing fast and loose with the facts. He grossly misunderstands me. Hypotheticals and counterfactuals are commonplace in both philosophy and social theory; they convey general conceptual distinctions in the context of a larger analytical development. That is how I use them in my book.

So, imagine that an observer (correctly) takes note of the fact that, on average and all else being equal, commercial loans to blacks pose a greater risk of default, or that black residential neighborhoods are more likely to decline. This may lead the observer to withhold credit from blacks, or to move away from any neighborhood when more than a few blacks move into it. But what if race conveys this information only because, when a great number of observers expect it to do so and act on that expectation, the result (through some possibly complex chain of social causation) confirms their beliefs? Perhaps blacks default more often precisely because they have trouble getting further extensions of credit in the face of a crisis. Or perhaps nonblack residents panic at the arrival of a few blacks, selling their homes too quickly and below the market value to lower-income (black) buyers, and it is this process that ends up promoting neighborhood decline.

If under such circumstances observers were to attribute racially disparate behaviors to deeply ingrained (biological or cultural) limitations of African-Americans-thinking, say, that blacks do not repay their loans or take care of their property because, for whatever reasons, they are just less responsible people on average-then these observers might well be mistaken. But because their supposition about blacks is supported by hard evidence, they might well persist in the error.2 Such an error, persisted in, would be of great political moment, because if one attributes an endogenous difference (a difference produced within a system of interactions) to an exogenous cause (a cause located outside that system), then one is unlikely to see any need for systemic reform. This distinction between endogenous and exogenous sources of social causation, I am arguing, is the key to understanding the difference in our reformist intuitions about gender inequalities in schools and in jails. That is, because we think the disparity in school outcomes stems from endogenous sources, while the disparity of jail outcomes is tacitly attributed in most of our "causal models" to exogenous sources, we respond to the disparities in different ways.

So when I talk about “racial stigma” and employ an apparently loaded phrase like “biased social cognition,” I do so because these terms allow us to see how the disadvantageous position of a racially defined population subgroup can be the product of a system of social interactions and not some quality intrinsic to the group. I reiterate that it hardly matters whether those intrinsic qualities mistakenly seen as the source of a group's lowly status are biological or cultural.3 What matters, I argue, is that something has gone wrong if observers fail to see systemic, endogenous interactions that lead to bad social outcomes for blacks, and instead attribute those results to exogenous factors taken as internal to the group in question. My contention—and neither Garcia nor McWhorter offers argument or evidence to refute it—is that in American society, when the group in question is blacks, the risk of this kind of causal misattribution is especially great.

I believe the disparate impact of the enforcement of anti-drug laws offers a telling illustration of the value in this way of thinking. Garcia disagrees. The sellers of drugs are more deeply involved in serious crime than are buyers, he says, and anyone with a moral sense knows that serious criminals deserve incarceration. Without necessarily disputing either of these claims, here is what I actually believe on this question: there can be no drug market without sellers and buyers. (Just so, there would be no street prostitution without hookers and johns.) Typically, those on the selling side of such markets are more deeply involved in crime and disproportionately drawn from the bottom rungs of society. When we entertain an alternative response to the social malady reflected in drug use (or in street prostitution), we must weight the costs likely to be imposed upon the people involved. Our tacit models of social causation will play a role in this process of evaluation. To ruin a college student's life because of a drug buy, or a businessman's reputation because of a pick-up in the red light district, may strike us as far more costly than to send a young thug to Riker's Island, or to put a floozy in the slammer.

One consequence of racial stigma, I suggest, is that because those bearing the brunt of the cost of our punitive response to the broad social malady of drug usage are disproportionately black, our society is less impelled to examine possible bias in this area of policy, and to consider reform. I could be wrong about this, but the speculation is certainly not implausible. How “serious” a given crime is seen to be in the minds of those who through their votes indirectly determine our policies, and how “deserved” the punishment for a given infraction, can depend on the racial identities of the parties involved. This, I am holding, is human nature. There need be nothing “sinister” in any of it. But if we want to analyze what is going on around us, and not merely moralize about it, we will want to take such possibilities seriously.

That is what I see myself as doing. I use the theory of biased social cognition that I have just sketched to argue that durable racial inequality can best be understood as the outgrowth of a series of “vicious circles of cumulative causation.” Tacit association of “blackness” with “unworthiness” in the American public's imagination affects cognitive processes and promotes essentialist causal misattributions. Confronted by the facts of racially disparate achievement, the racially disproportionate transgression of legal strictures, and racially unequal development of productive potential, observers will have difficulty identifying with the plight of a group of people whom they (mistakenly) think are simply “reaping what they have sown.” So there will be little public support for egalitarian policies benefiting a stigmatized racial group. This, in turn, encourages the reproduction through time of racial inequality because, absent some policies of this sort, the low social conditions of many blacks persist, the negative social meanings ascribed to blackness are thereby reinforced, and so the racially biased social-cognitive processes are reproduced, completing the circle.

What is more, I argue that this situation constitutes a gross historical injustice in American society. Again, Garcia disagrees. He thinks we act legitimately to reduce racial equality only when we are moved by a desire to promote comity and community, but not when we are pursuing “racial justice.” He praises me for my opposition to slavery reparations, but takes me to task for seeing racial inequalities on the scale so evident in con- temporary American life as a problem of justice. Yet these two positions are very closely linked. In my view, present racial inequality is a problem of justice because it has its root in past unjust acts that were perpetrated on the basis of race. I see past racial injustice as establishing a general presumption against indifference to present racial inequality.

To see why this matters, suppose it could be shown that a posture of official public indifference to racial inequality would enhance our comity and community. (So, it would seem, many advocates of a “color-blind” America believe.) Even if this were the case, I would still urge that some efforts to reduce racial inequality would be warranted. However, those efforts should not be conceived in terms of “correcting” or “balancing” for historical violation. This is what leads me to reject reparations. In my view, although the quantitative attribution of causal weight to distant historical events required by reparations advocacy is not workable, one can still sup- port qualitative claims.

Reparations advocates conceive the problem of our morally problematic racial history in compensatory terms. By contrast, I see the problem in interpretative terms. That is, I seek public recognition of the severity, and (crucially) the contemporary relevance, of what has transpired. The goal is to encourage a common basis of historical memory-a common narrative-through which the past racial injury and its continuing significance can enter into current policy discourse. What is required for racial justice, as I conceive it, is a commitment on the part of the public, the political elite, the opinion-shaping media, and so on to take responsibility for the plight of the urban black poor, and to understand this troubling circumstance as having emerged out of an ethically indefensible past. Such a commitment should, in my view, be open-ended and not contingent on demonstrating any specific lines of causality. Again, I could be wrong about this, though neither Garcia nor McWhorter gives argument or evidence to disabuse me of this view. And should a critic agree with my judgment here but prefer not to use the word “justice” in reference to it, that would be a matter of little consequence.

I turn now from the argument of my book to a consideration of the larger political context into which my argument has been injected. John McWhorter thinks The Anatomy of Racial Inequality marks a “coming out” for me as some kind of leftist after my many years of faithful service on the conservative side of this question-the side that he favors. This, I fear, is a gross mischaracterization. This book is an exercise in social theory, not in polemics, and anyone who spends five minutes perusing it will see as much. My goal with this exercise has been to understand something of how race, racial identity, and racial classification work in the social life of this nation. Any such endeavor self-consciously undertaken as an expression of political ideology is bound to fail. There are literatures in economics, sociology, and social psychology to which I hope to contribute with this work. I cannot be sure I have succeeded-this is up to my scholarly peers to decide. But the one thing I am certain of is that in the writing of this book I have had no political agenda.

McWhorter perceives a harrowing psychodrama in which the “good” (conservative) Loury becomes “possessed” by some “bad” (left-leaning author of this book) Loury. If what the Loury writing in 2002 has to say about racial inequality differs from the views of Loury writing in 1985, McWhorter can envision only two explanations: either the latter-day Loury is an opportunist shifting his views to curry favor and advance his career; or, he is an emotional wreck, exhausted from doing battle with the civil rights establishment. McWhorter has the temerity, the audacity, to write: “By the late 1990s, a series of personal crises began to lead Loury to question his earlier views.”

How on earth would he (or anyone, for that matter) know that, and what is such uninformed psychological speculation doing in a book review? I very much regret that John McWhorter has drawn me into such an ad hominem discussion, in the pages of a journal of ideas on whose editorial advisory board I have served for nearly a decade, but so be it. The “crises” to which he refers occurred in the 1980s, fifteen years before the publication of this book, and many years before I left the conservative camp. I have been speaking publicly and writing critically on race-related matters since 1982. If the heat of controversy was going to prove too much for me, why didn't this happen in the early 1980s when I aligned myself with the Reagan Administration, or in the late 1980s when I was publicly humiliated by “personal crises,” or in the early 1990s when a centrist Democratic administration might have opened its doors to me? In short, McWhorter's narrative is an irrelevant piece of fiction that tells the reader a good deal more about him (the happy warrior, hacking away on the frontlines of the Kulturkampf), and about the movement of which he is now a part, than it tells about me.

Moving along, what are we to make of his reaction to my argument? In a word, it lacks cogency. Item: I do not argue that people view others in society through the lens of the scientific paradigms made famous by Thomas Kuhn. Rather, I hold that people adopt modes of learning about the underlying causes of social outcomes that, in their lack of a fully rational cognitive foundation, may be usefully likened to what Kuhn proposed about the way scientific communities assimilate new theories. Item: I do not say that people form their beliefs based on their desire to belong to one community or another. Rather, I hypothesize that if we are to understand how people acquire the mechanisms of symbolic expression peculiar to the communities in which they are embedded we must consider the meaning of their relations with others in those communities. Item: I do not suggest that the tendency toward social generalization leads blacks to suffer from “reward bias.” To the contrary, I explicitly state that such bias is no longer a major factor in accounting for black disadvantage.4 On the evidence at hand, I am forced to conclude that McWhorter does not comprehend the argument of my book.

Despite these misunderstandings, he thinks my theory “solid,” and perhaps I should be thankful for small favors. But the honeymoon is short-lived! He turns sour on Chapter Three, where I give racial stigma a central role in my thinking, thereby promoting the idea, he thinks, that “history is destiny” for black people. But this is just more confusion. It is an empirical question answerable by social science as to whether or not the racial stigma that I have discussed here is an important impediment to blacks' social advancement. In contrast, it is a moral and philosophical question-even an existential/spiritual matter-answerable by reference to the values and traditions of black American people as to whether this or any other obstacle we might encounter along life's path should be seen as fundamentally determining our destinies. An analysis of the social-structural factors impeding black progress need not be a counsel of passivity. To the contrary, such an analysis is the essential first step in any program of rational action.

McWhorter accuses me of quietly endorsing leftist positions because he imagines some leftists may agree with what I have written. He actually thinks this is a reason to reject my argument. Continuing in this vein, he tars me with the brush of association with the hated Jesse Jackson (why not up the ante and make it Al Sharpton?) simply because I used a phrase with a pithy rhyme, as Jackson is wont to do. He thinks that I have forgotten what I used to know about the history of black people, and particularly about the origins of the underclass. And what is this forgotten truth? It is that the tragic conditions in today's ghettos are “due less to slavery's legacy than to the rise of the New Left in the 1960s.”

I most certainly have not “forgotten” this purported truth about black American history. I never knew any such thing, for the good and sufficient reason that it is not true. Black power ideology led to an oppositional culture in the ghettos, McWhorter says. Guilt-ridden whites gave the black poor free handouts with AFDC programs that paid them to have children and lured them into dependency. Racial preferences kept black students from ever learning what serious effort entails. Concerning this cartoon version of American social his- tory, my reaction is best captured in the phrase made famous by Howard Beale, the “mad prophet of the air waves” in the film Network: “I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it any more!”

Indeed, it was this kind of mindless sloganeering about the serious problems afflicting poor black people that drove me from the conservative ranks in the first place, in defense of my own intellectual integrity. Missing from McWhorter's underclass morality tale are a few factors that most social historians rightly find to be significant: deindustrialization in the “rust belt” cities; a huge, relatively low-skilled immigration quickening competition at the labor market's bottom rungs; fierce resistance by working-class whites to housing and school integration for decades after segregation had been legally proscribed; technological innovations such as the birth control pill, which helped to alter sexual mores across the class structure, and crack cocaine, which, along with the easy availability of guns, changed life in inner cities across America; the demolishing of low-rent housing through slum clearance and replacement of these units with massive high-rise public housing projects sited exclusively in black residential districts. One could go on in this vein, but this should suffice to make my point: he who thinks the underclass is the product of a bunch of 1960s moral relativists knows not what he is talking about.

Were McWhorter to take a glance at the wealth of historical scholarship on the roots of social decay in American cities (Tom Sugrue's prize-winning study of Detroit in the quarter century after World War II, The Origins of the Urban Crisis, is a good place to start), he would discover just how superficial and tendentious his characterization appears. The greatest of the “black power ideologues” was the Nation of Islam's Malcolm X—a puritan on cultural matters. If the family values, work ethic, and concern with self-improvement on display at the 1995 Million Man March give any indication of what an “oppositional culture” can produce, then such “opposition” can hardly explain poor social performance among black people. Real welfare payments fell continually for a quarter century between 1970 and the advent of welfare reform, even as the size of the ghetto underclass constantly grew. If paying women to have babies led to black welfare dependency, then did they elect to increase their “supply of babies” as the pay rate fell? Race preferences at the college level affected a minuscule fraction of black students until well into the 1980s, and even now reach only a minority (since three-fifths of American colleges and universities admit all who apply and meet minimal qualifications). How, then, could this set of policies account for the behavior of millions of black students?

Having gotten that off my chest, let me now make a confession. I think I know where the animus in McWhorter's review is coming from, and I admit that I am partly to blame. He, along with many of my former comrades, is disappointed in and confused about my current position, and for good reason: I seem now to be contradicting some of the most powerful arguments that I advanced against racial liberalism in the past. Thus, ten years ago, in the pages of this very journal, I wrote the following:

It is time to recognize that further progress toward the attainment of equality for black Americans, broadly and correctly understood, depends most crucially at this juncture on the acknowledgment and rectification of the dys- functional behaviors which plague black com- munities, and which so offend and threaten oth- ers. Recognize this, and much else will follow. It is more important to address this matter effectively than it is to agitate for additional rights. Indeed, success in such agitation has become contingent upon effective reform efforts mount- ed from within the black community....

The [key] point... is [that] progress such as this must be earned, it cannot be demanded.... When the effect of past oppression is to leave a people in a diminished state, the attainment of true equality with the former oppressor cannot depend on his generosity, but must ultimately derive from an elevation of their selves above the state of diminishment. It is of no moment that historic wrongs may have caused current deprivation, for justice is not the issue here. The issues are dignity, respect, and self-respect-all of which are preconditions for true equality between any peoples. The classic interplay between the aggrieved black and the guilty white, in which the former demands and the lat- ter conveys recognition of historic injustice, is not an exchange among equals. Neither, one suspects, is it a stable exchange. Eventually it may shade into something else, something less noble-into patronage, into a situation where the guilty one comes to have contempt for the claimant, and the claimant comes to feel shame, and its natural accompaniment, rage, at his impotence. ("Two Paths to Black Power," FT, October 1992)

How, I imagine McWhorter, Garcia, and a great many others must be asking, can the man who wrote those words make racial stigma the central organizing principle of his “anatomy of racial inequality”? This is neither the time nor the place for me to fully address that question, but I can offer this partial reply. It is not inconsistent to hold that black parents are responsible for the values embraced by their children and simultaneously to hold that the nation also bears some responsibility for the suffering of the ghetto poor. Nor is it a contradiction to assert, at one and the same time, that profound behavioral problems afflict many black communities and that these maladies are no alien imposition on an otherwise pristine Euro-American canvas, but instead arise from economic and political structures indigenous to American society. Both can be true. And if both are true, the question becomes one of emphasis. While my emphasis has definitely changed, I have not repudiated my earlier claims.

The deeper issue, though, is the difficulty of coherently and effectively voicing both truths when one endeavors to practice social criticism in a “multiple audience” context. Whenever a black critic advances an argument for any kind of reform, he faces two audiences, a communal one and a civic one. The passage from 1992 quoted above was an exercise in social criticism directed, ironically, at black American intellectual and political leaders. (This is ironic because the piece was surely better known among and more widely cited by whites.) And my recently published book is an exercise in social criticism directed at the broad American elite as a whole. In 1992 I was preoccupied with the questions of dignity and self-respect for black people. These are inherently communal questions, which is not to say that only blacks can speak of such matters, or that blacks must speak only among themselves about them. But it is to acknowledge that, for the most part, they are matters where blacks must take the lead in defining the goals and managing the processes of moving toward them. But questions of social justice and fair opportunity are the fit subjects of a broader public discourse. And where the historical echoes of the racial subordination of African Americans continue to bear on such questions, we must not shrink from saying so.

The ultimate difficulty here is that, while self-development is an existential necessity for blacks as an ethnic community, its advocacy by black social critics in the larger civic discourse often undercuts the pursuit of racial justice, because people are authorized to see a problem of black culture instead of a problem of racial justice, when in fact both problems are there. (And, conversely, advocacy for racial justice can undercut communal reform by leading blacks to not see the culture problem.) This difficulty is reflected in the dual meaning of “we” implicit in the signature question I raise in my book: “What manner of people are we who accept such degradation in our midst?” There are two implied imperatives getting the “cultural trains to run on time” in black communities, and addressing the structural legacy of generations of racial oppression—and they rest on very different grounds. Whereas the first draws on ties of blood, shared history, and common faith, the second endeavors to achieve an integration of the most wretched, despised, and feared of our fellows along with the rest of us into a single political community of mutual concern.

This problem is closely related to the age-old conundrum of reconciling individual and social responsibilities. We humans, while undertaking our life projects, find ourselves constrained by social and cultural influences beyond our control. Yet if we are to live effective and dignified lives, we must behave as if we can indeed determine our fates. Similarly, black Americans are con- strained by the residual effects of an ugly history of racism. Yet seizing what the iconic black conservative Booker T. Washington once called “freedom in the larger and higher sense” requires that blacks accept responsibility for our own fate even though the effects of this immoral past remain with us. But our doing so cannot be allowed to excuse the nation from acknowledging a basic moral truth—one that transcends politics-which is that the citizens of this republic bear a responsibility to be actively engaged in changing the structures that constrain the black poor, so that they can more effectively exercise their inherent and morally required capacity to choose.

So, I was on a moral crusade in 1992. I am on a rather different quest now, but they are complementary, not contradictory, endeavors. Then I was sure that the biggest obstacle to incorporating the ghetto poor into the commonwealth was that their leaders had the wrong ideas. Now I think that was a mistake and I am laboring to correct the error. (Of course, some of these leaders still have bad ideas, but they are not alone in this.) As I say in the conclusion of my book, the role of a responsible black public intellectual today is to keep in play an awareness of the need for both communal and civic reforms, finding a way to make progress in either sphere complement that in the other.

Still, playing that role credibly is not easy. The larger currents of American public life inhibit nuance in dis- course about race and social policy (by commentators of all races). Moreover, there is something inevitably emblematic about the role that a prominent black intellectual like myself plays in such discussions.5 This role of “tacit testifying” that black dissenters inevitably play when they publicly break ranks from their co-racialists accounts for why we tend to be so easily pigeonholed in, and so willing to remain confined to, one ideological camp or the other. And it also helps to explain why when we change our minds, many people—liberals and conservatives alike—think they smell a rat. They are wrong.

It is worth noting here that a number of distinguished modern scientists disagree with them. Steven Pinker of MIT, in his forthcoming book, The Blank Slate, stresses that races are not discrete, non-overlapping categories but nevertheless argues that what we perceive as race has some biological reality as a statistical concept. A similar position is adopted by geneticist James Crow and zoologist Ernst Mayr, both Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, writing separately in the Winter 2002 issue of Daedalus.

Oddly, Garcia chastises me for introducing the possibility through these thought experiments that there might be truth to stereotypical beliefs such as “black neighborhoods tend to decline.” He thinks the relevant analysis of racial stereotypes must expose the lack of virtue of those who persist in holding false generalizations about some group. But this is a willful misreading, one which I find difficult to understand since I write explicitly in my book (on page 24) that, while the common parlance definition of “stereotype” has a connotation of unreasonableness, a “stereotype being a false or too simplistic surmise about some group: ‘blacks are lazy,’ ‘Jews are cunning,’ and so on, this crude overgeneralizing behavior... is not my subject. Rather, my model of stereotypes is designed to show the limited sense in which even ‘reasonable’ generalizations, those for which ample supporting evidence can be found, are fully ‘rational.’ I argue that such generalizations often represent instances of what I will refer to as ‘biased social cognition.’” Surely there is nothing shocking about this, nor can there be any doubt as to the relevance of my analysis of stereotypes (in the sense that I use the term) for understanding the problem of persistent racial inequality.

Thus, Garcia's distinction in this regard—between Charles Murray (who, he says, may be an essentialist, since Murray thinks blacks are intellectually inferior for genetic reasons), and Dinesh D'Souza (who, he says, couldn't possibly be an essentialist, since he simply thinks that blacks are uncivilized)—is largely beside the point.

McWhorter gets this part of my argument exactly backwards. According to him, I think development bias is no longer a problem for blacks, and believe a stigma-induced reward bias now limits black life-chances. Has he read the book? Here is what I write there: “Another name for the reward bias argument is discrimination.... I am not enthusiastic about this concept; I argue here that it should be... dislodged from its current prominent place in the conceptual discourse on racial inequality in American life [because of] . conviction that racial discrimination, as an my analytical category, cannot reach the problem of development bias.... And yet I see the development bias argument as the more promising one... for two reasons. In the first place, it explains the extent and durability of current racial inequality more effectively. But more important, the dilemmas of public morality created by racial inequality in the United States... can be fully illuminated only when the development bias problem is placed at center stage.” (Pages 93-94, emphasis added.)

Consider how the race of the author has contributed to the credibility of the arguments in books like McWhorter’s Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America and Randall Kennedy’s recent Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word. The importance of the author’s race in these cases is due not so much to the possibility that he has access to inside information. Rather, the key point is that the argument’s legitimacy, not its accuracy, can be enhanced by an author’s race. (“Even some blacks can see that …”) But legitimacy depends on what a reader can safely assume about an author’s motives. As a result, social criticism on race-related topics by black writers inescapably entails an ad hominem element.

![The Anatomy of Racial Inequality [Book] The Anatomy of Racial Inequality [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jahz!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fed4b7861-06e2-480b-913d-216a9b9fbd32_660x1000.jpeg)

This is really, really good stuff and an important piece of Glenn Loury archaeology since he has not fundamentally changed his mind about many of the ideas in it.

My question about centering "biased social cognition" is not as much about its veracity (which matters a lot to me in some areas, but in this case I'm not seeing that it's clearly enough defined, nor falsifiable enough, to discern any objective truth), than about whether in the ensuing decades it has shown itself to be fruitful framing which advances desirable outcomes.

I currently perceive the current fixation on "systemic racism" (as used in contemporary political discourse) to be based more on the psychological payoffs of it as an ego-salving framing, than on seeking the most effective tools for improving the real world problems it nominally seeks to explain. As such, "systemic racism" rarely submits to neutral evaluation, preferring to operate by ideologically ignoring any alternative explanations in favor of those which support the desire narrative.

I'm wondering if "biased social cognition" avoids those pitfalls.