The question of how or if America can move beyond racial categorization has become a hot topic here at The Glenn Show. Over the last year, several guests, including John McWhorter, have weighed in. One of the most ardent supporters of deracialization that I’ve spoken to is Greg Thomas, CEO and co-founder of the Jazz Leadership Project and a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Cultural Evolution. Greg’s essay, “Deracialization Now,” began as a response to both me and my frequent correspondent Clifton Roscoe. Clifton and I have each, in our own ways, voiced some skepticism about the feasibility of doing away with racial categories, at least in the near term. Greg, however, argues that deracialization is possible, and sooner rather than later. Indeed, he thinks deracialization is imperative.

I invited Clifton to respond to Greg, and that kicked off a correspondence between them on the subject (I got the ball rolling with an excerpt from the new preface to The Anatomy of Racial Inequality). You’ll find that correspondence below. I’ll withhold further comment on the matter here, as I think both Greg and Clifton argue their respective sides of the argument rigorously and forcefully. Let’s keep the conversation going—I’m looking forward to reading your comments.

Note: This post’s size exceeds that allowed by most email services. We recommend that you read it on either your web browser or Substack’s mobile app.

This post is free and available to the public. To receive early access to TGS episodes, an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

Dear Greg,

Below please find a lightly edited excerpt from the preface to the 2nd edition of The Anatomy of Racial Inequality, my book that Harvard University Press published last year. (The 1st edition was based on my 2000 DuBois Lectures and appeared in 2002.) I commend it to your attention considering our recent exchange at my podcast in the hope that you will be motivated to respond to the arguments on offer. I defend the use of the concept of “race,” which I define as “embodied social signification.” As well, I reject as fallacious your “ontological refutation” of the idea of “race” (i.e., the argument that “since there is no such thing as a ‘race,’ it is illogical to think of oneself as being ‘raced.’”) I look forward to your response.

Best wishes,

Glenn

Any theory of “race” must reckon with the fact that people take note of and assign significance to superficial markings on the bodies of other human beings—their skin color, hair texture, facial bone structures, and so forth. This universal human practice appears to have a deep neurological foundation. This is the point of departure for my analysis. I refer to a society as being “raced” when its members routinely partition the field of human subjects whom they encounter in that society into groups, where this sorting convention is based on the subjects’ possession of some cluster of observable bodily marks. This leads to my claim that, at bottom, “race” is all about “embodied social signification.”

Let us call this the social-cognitive approach to thinking about “race.” It can be usefully contrasted with an approach derived from the science of biological taxonomy, in which one classifies human beings based on the natural variation in genetic endowments across geographically isolated subpopulations. Such isolation was a feature of the human condition until recently (on an evolutionary time scale), permitting there to be some independent biological development within subpopulations that might be thought to have led to the emergence of distinct “races.” Of course, this idea of “biological race” is controversial. When philosophers deny the reality of “race,” they have in mind this biological-taxonomic notion, and what they deny is that meaningful distinctions among contemporary human subgroups can be derived in this way. Whether they are right or not is a scientific question that lies beyond the scope of this book.

But, whatever the merits of that dispute, I am at pains to stress that the validity of racial classification as an exercise in biological taxonomy is conceptually distinct from the validity (and relevance) of my concern with racial categorization as an exercise in social cognition. The social convention of thinking about other people (or oneself, for that matter) as belonging to different “races” is a deeply ingrained feature of our political culture that has taken on a life of its own. As I see it, the logical exercise of deconstructing racial categories by arguing that nothing “real” lies behind them is largely beside the point.

Thus, my approach to the concept of “race” is cognitive, not normative. (I.e., I am interested in understanding people’s behavior, not in judging it.) This approach is exemplified by the theory of “self-confirming racial stereotypes” that I advanced in my first Du Bois lecture. My point here is a subtle one, so permit me to explain it a bit further by means of the following thought experiment.

Imagine that people believe fluctuations of the stock market can be predicted by changes in sunspot activity. This may be because, as an objective meteorological matter, sunspots correlate with rainfall, influencing crop yields and thus affecting the economy. Or, alternatively, solar radiation might influence the human psyche somehow, so as to alter people’s behavior in the securities markets. Each of these two accounts postulate an objective causal link between sunspots and stock prices, analogous to grounding one’s cognizance of “race” on the validity of a race-based biological taxonomy. Still, even if no such objective link as this between sunspots and stock prices exist, so long as enough people believe in the connection, monitor weather on the sun’s surface, and act based on how they anticipate security prices to be affected, then a real link between these evidently disparate phenomena can emerge from the subjective perceptions of market participants. As a result, belief in the financial relevance of sunspot activity will have been rendered entirely rational. Can you see this allegory’s important implication?

It is this: that no objective basis for a racial taxonomy is necessary for the subjective use of racial categories to be warranted.

For, if a person knows that others in society will classify him based on certain markers, and if such classification impacts his material well-being, then it will be a rational stance on his part—not an unfounded belief and certainly not a moral error—for him to see himself as being “raced.” In turn, that he thinks of himself in this way and that his societal peers are inclined to classify him as such can provide a compelling reason for newcomers to that society to adopt this ongoing scheme of racial classification. Learning the extant “language” of embodied social signification is a first step toward assimilation for the foreigner, or the newborn, into any “raced” society. In this way, “races” (in this social-cognitive sense) may come to exist and to be reproduced over the generations in a society, even though there may be no “races” in the biological-taxonomic sense. The “social-cognitive” and the “ontological” arguments are talking about completely different things. As such, disputing the scientific existence of “races” need not have any bearing on the legitimacy or rationality of using racial classifications in social practice. That is, understanding how “race” operates within the American social hierarchy, which is the purpose of this book, will be facilitated by thinking of “race” as “embodied social signification.” This move on my part is both logically coherent and analytically useful.

That is, I take “race” to be a social convention. So, I approach it from a cognitive not a normative point of view. For me, the term “race” refers to indelible, heritable marks on human bodies—skin color, hair texture, facial bone structure – marks that may be of no intrinsic significance but nevertheless that have through time come to be invested with social expectations and social meanings that are durable. All of this is to be understood as taking place within a given society, and as emerging out of a specific historical context.

Two distinct processes are implicated here: categorization and signification. By categorization I mean the sorting of people into groups based on their bodily marks, so as to differentiate one’s dealings with such persons. This is, I argue, a basic and necessary effort to comprehend the social world around us. By signification I intend to evoke an interpretative act—one that associates certain connotations, or “social meanings,” with those categories. So, informational and symbolic issues are both at play. Or, as I put it in the book, when invoking the term, “race,” what I am actually talking about is “embodied social signification.” To dismiss this as “racial essentialism” would be to completely misunderstand me.

Dear Glenn,

I hadn't seen Greg Thomas's “refutation” before this week. I scanned it and printed it out for a more careful read. I'm not sure what to make of it. We all seem to agree that today's highly racialized environment is bad, but I didn't get a clear sense of what his deracialized replacement looks like. Does he want the government to stop collecting racial data? Should we stop worrying about noticeable differences across the races (e.g., academic achievement gap, income gap, employment gap, wealth gap, life expectancy gap, differences in poverty rates, differences in incarceration rates, differences in criminal victimization rates, etc.)? What about differences relating to gender, age, sexual orientation, and other noticeable differences between easily identified groups of Americans? Should we stop worrying about them too? Should we abandon the concept of hate crimes? A lot of people would be relieved if these things happened, but we might not be a better country if we ignored these issues.

Last but not least, I didn't get a clear sense of what Greg Thomas thinks “blackness” should be. Can it be reduced to just culture? Does he think we should give up most black institutions since many of them perceive their missions to include more than just preserving black culture?

To make a long story short, Greg Thomas's essay raised more questions for me than it answered.

Clifton

Racial Worldview vs. Nonracial Worldview

Response by Greg Thomas

Thanks Glenn, for sharing your theory of race as “embodied social signification.” My argument in favor of deracialization doesn’t deny that, in the United States and beyond, human beings have been “raced” or “racialized.” You, I, and many millions of others continue to be racialized.

The question is whether you, I, and others will continue to accept such racialization. Recall the wise vernacular expression: It ain’t what you call me, it’s what I answer to. Just because we’ve been ascribed a racial identity doesn’t mean we should continue subscribing to it. Let’s cut the racial cord and cancel the subscription while maintaining fidelity to our ancestral heritage and shared culture.

I agree with Dr. Sheena Mason, author of Theory of Racelessness: “The practice of racialization assaults people’s ethnic, class, and cultural distinctions by sometimes obliterating or often obscuring how culture, class, and ethnicity exist.” This was a key point of my “Deracialization Now” essay response to you and Clifton Roscoe.

In my estimation, your theory of race remains affixed to a racial lens, a racial paradigm, a racial worldview. I reject race, racialization, and a racial worldview because they inevitably compound and evince as racism. I disavow the contemporary concept of race because its very function and design is dehumanizing. Persons racialized as “black” were considered a “sub-species” of human beings. No wonder “stigma” has trailed the experience of native-born, multi-generation Afro-Americans as a people.

I also renounce and rebuke racialization, which, according to Carlos Hoyt Jr. in The Arc of a Bad Idea: Understanding and Transcending Race, is:

Selecting some human characteristics as meaningful signs of “racial” differences (phenotype and ancestry)

Sorting people into human subpopulations called races based on variations in those characteristics (skin color, hair texture, size of nose)

Attributing personality traits, behavior, and other characteristics to people classified as members of particular races (stereotypes such as “shiftless and lazy”)

Essentializing so-called racial differences as natural, immutable, and hereditary

Acting as if arbitrary “racial” differences justify unequal treatment (based, in part, on what you deem “social expectations and social meanings that are durable,” Glenn.)

Furthermore, I repudiate a racial worldview. According to cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, a “worldview is two things simultaneously: (1) a model of the world and (2) a model for acting in that world. It turns the individual into an agent who acts, and it turns the world into an arena in which those actions make sense.”

Let’s apply race to this definition: “A (racial) worldview is two things simultaneously: (1) a (racial) model of the world and (2) a model for acting in that (racial) world. It turns the individual into a (racial) agent who acts, and it turns the world into a (racial) arena in which those actions make sense.”

Let’s break away from being racial agents acting in a racial arena and racial world, whereby the following vicious cycle persists, into perpetuity.

There is a growing body of work based on a heterodox perspective my colleagues and I call a non-racial worldview. Dr. Carlos Hoyt, author of The Arc of a Bad Idea: Understanding and Transcending Race, has composed a list for this symposium titled “A Nonracial Worldview Library.” I commend it to your attention.

Regarding Mr. Roscoe’s questions, a few brief responses:

“Do I want the government to stop collecting racial data?” No, I think the government should collect more data via the US Census, including a category for those who would prefer to opt out of imposed self-racialization altogether. Additionally, as mentioned in my original essay, persons should be able to indicate how they perceive they are racialized by others. Why? To continue tracking discrimination based on racial ascription.

“Should we stop worrying about noticeable differences across the races in significant categories?” The very question reifies race by presuming the existence of so-called “races.” We should most certainly be aware of gaps among people who have been racialized or self-identify in racial terms but only after flipping-the-script on the deficit-framing which centers people racialized as “white” as the norm for comparison. Trabian Shorters, the founder of the BMe Community, argues that a better cognitive and narrative practice begins with people’s aspirations, acknowledges their accomplishments and achievements, and then focuses on their challenges.

For instance, how often do we hear about the 2006-2010 Center for Disease Control study, indicating that black identified men, regardless of marital status, have the most active engagement with their children? “Black fathers (70%) were most likely to have bathed, dressed, diapered, or helped their children use the toilet every day compared with white (60%) and Hispanic fathers (45%).”

Why not mention the high rates of black-identified philanthropic giving and entrepreneurship, especially by women identified as black? Why the incessant litany of liabilities as if that’s the only story worth discussing?

“Should we give up black [identified] institutions?” Of course not. Such institutions, created in the smithy of racial domination and the forging of political and cultural resistance, were and remain havens for our communal solidarity and resilience. Furthermore, jazz and other artistic manifestations of our idiomatic culture are still sites for the expression of our—by which I mean all Americans—highest values, meanings, and aspirations.

That’s why I advocate for a cultural, rather than a racial, worldview: “A (cultural) worldview is two things simultaneously: (1) a (cultural) model of the world and (2) a model for acting in that (cultural) world. It turns the individual into a (cultural) agent who acts, and it turns the world into a (cultural) arena in which those actions make sense.”

Race, created by racialization, is reinforced by racism, and perpetuated through the social-cognitive prison of a “racial worldview” apparatus. As jazz pianist and bandleader Vijay Iyer once told me, we “must soar beyond their apparatus.” The price of the ticket for this heroic journey toward transracial humanism is deracialization, while maintaining rooted ethno-cultural commitments within a shared cosmopolitan and plural Omni-American identity.

Special thanks to Carlos Hoyt, Jewel Kinch-Thomas, Adrian Lyles, Sheena Mason, and Gilbert Morris for their perspicacious feedback, which brought into clear focus several points above.

Dear Greg,

The only thing I might add is that I come from an engineering/business background. “Bench marking” is often used to gain the insights needed to reduce performance differences between products, services, groups, etc. Jim Collins talked about the importance of “confronting the brutal facts” in his book Good to Great. We can't close all the gaps I mentioned above (e.g., academic achievement gap, income gap, employment gap, wealth gap, life expectancy gap, differences in poverty rates, differences in incarceration rates, differences in criminal victimization rates, etc.) by ignoring them or trying to offset them with other racial metrics that don't hold up under close scrutiny (e.g., black fathers are more engaged with their children than their peers) or aren't nearly as consequential as the ones I mentioned (e.g., black philanthropic giving, black female entrepreneurship).

John Washington wrote a long essay for Quillette last March (“AWOL Black Fathers”) that I find more persuasive than self-reported survey data. What father wouldn't say he spends lots of time with his children?

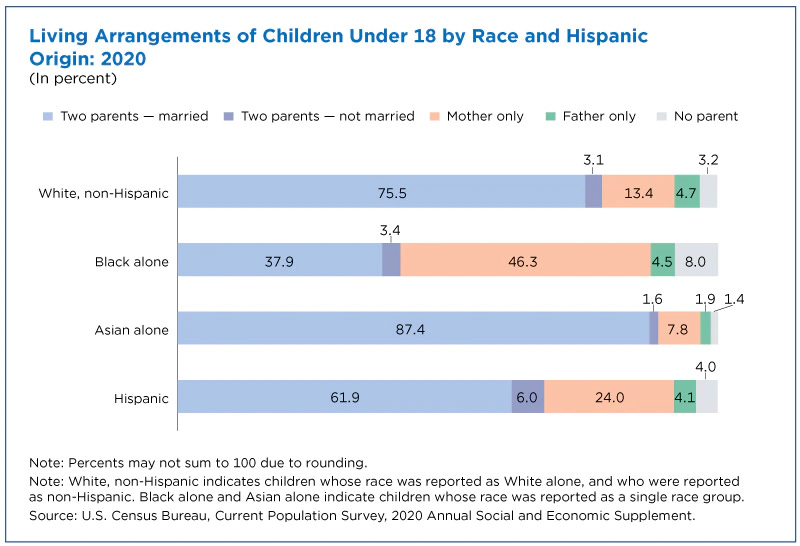

Black family structures can help us get at the truth. They are more fractured than those of other groups according to data from the US Census Bureau.

Here's a graphic that shows stark differences:

I'd be willing to wager that black children spend less time with their fathers than their peers, given that they are less likely to live in households with two parents and more likely to live in households with no parents.

There's also the issue of “multiple partner fertility” (think Nick Cannon) that Glenn has discussed with Robert Cherry on his show. A Child Trends analysis from 2006 shows that black men are twice as likely to have children with more than one woman than their white and Hispanic peers. Use this link, download the analysis and go to Figure 6 if you have doubts. Does anybody think fathers who have children with multiple women spend more time with their children than men who only have children with one woman? Not me. How about men who have children with multiple women compared to men who have children with one woman and live with their children and their children's mother? Do we think they spend more time with their children? I don't.

The philanthropy and entrepreneurial data that was referenced in Greg Thomas' contribution don't hold up under close scrutiny. Data from the St. Louis Fed show a big wealth gap.

Black philanthropy starts from a position of relative weakness once you account for the wealth gap. Conversations I've had with people who hold positions within black institutions confirm this. They wish black philanthropy was more consequential and that they weren't so dependent upon non-black donors.

While it is encouraging that black women are starting businesses, we have to keep in mind that less than five percent of black businesses have employees according to the Small Business Administration. Here's a graphic:

This analysis was published in 2016. More recent data from the SBA suggests that black-owned businesses, especially those owned by black women, were hit hard by the pandemic.

It's also worth noting that data from the US Census Bureau suggests that black entrepreneurship has not translated into wealth. Data from 2020 shows that black people are less likely to hold equity in businesses or professions and the values of their holdings are lower than those of whites and Asians when they do. Use this link, download the Wealth and Asset Ownership workbook, and go to Tables 1 and 2 for details.

My point here is not to beat you to death with data, but to suggest that you can't fix a problem until you understand it. It's difficult to understand a problem without good information. False narratives are common in Black America because not enough people have good information. The impacts of false narratives are often catastrophic (e.g., Ferguson after Michael Brown, Baltimore after Freddie Gray, Kenosha after Jacob Blake). The lack of black progress over the past 30-40 years, misplaced priorities, and poor problem solving reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of the issues facing Black America.

Best regards,

Clifton Roscoe

Black Americans: Perspectival Shifts, Possibilities, and Predicaments

Seems that we are comparing apples and oranges, Clifton. I’m emphasizing a vision of an American future in which race, racialization, and racism, all driven by a superordinate racial worldview, do not hold the same chokehold on our minds and behavior as they have since the eighteenth century. Your focus is on the statistical gaps between racialized black folk and other ethnic and racialized groups in contemporary America in academic achievement, income, employment, wealth, life expectancy, poverty rates, incarceration rates, criminal victimization, and so on.

I don’t deny that the problems and predicaments you point to are real and crucial to address. They are the downstream effects of a range of factors—systemic to familial to the individual—in which maladaptive choices and behavior predominate far too often. You shot down my mention of a few instances of positive markers among Afro-Americans. Perhaps you’ll also downplay as no big deal the rising middle-class and the higher post-secondary education rates among US Black Americans post-Jim Crow. So be it. I’ll defer to your prowess with statistics and graphs.

I won’t defer, however, in the arena of vision, which informs strategies and tactics. Neither will I leave the discussion of statistical gaps or high rates of maladaptive behavior without asking: Are the gaps in education, income and wealth, life expectancy, poverty, incarceration, and the like due to the color of skin of “black” people? Or, rather, the size of their noses or the texture of hair? We certainly agree, I trust, that such absurd biological essentialism is not determinative.

So is “race” a cause of these results? Perhaps a better question is whether the “racialized status” of multi-generations of Afro-Americans is a key factor. It behooves us to consider, for instance, whether commercial (redlining by banks) and state-sponsored bias and discrimination (not allowing Black American veterans to take advantage of the G.I. Bill, for instance) might have anything to do with lagging homeownership rates and the wealth gap? And yet today there are approximately 340,000 “black” families in the United States with a net worth of $1 million or more. Isn’t this achievement—as Glenn says, “We are the richest black people in the world”—worth even a passing mention?

Cultural and developmental deficits do not tell the whole story. To the extent that culture is the means through which human beings adapt to their social, political, economic, and familial environments, dysfunction among some people who share phenotypic characteristics is indicative of maladjustments to the norms and demands of modernity. However, in the same way that we can comprehend how opioid addicts in Ohio and West Virginia are not victimized by deficits in “white” culture, those caught in a web of gang and gun violence and destruction in urban, predominantly Afro-American and Hispanic neighborhoods are not victimized by deficits in “black” culture. In both cases, to be sure, people must be held to account for criminality derived from cultural maladaptation, but let’s also not excuse or ignore the socio-economic supply chain, moral slobbism, and market forces that enable, rather than deter, such behavior.

Bottom line: Culture, history, and the economy factor into the statistics you cite, Clifton. Racial status is important, but it’s ultimately secondary to the combined dynamic of these larger considerations. Case in point: Are the social maladies that we see in Chicago, in terms of gun violence and its aftermath, the same in predominately “black” locales such as Hillcrest, New York or Prince George’s County in Maryland? If race was determinative—rather than socialization, habituation, class, marital status, and education level—then wouldn’t we see evidence of anti-social violence in those places too?1

What is your vision, Mr. Roscoe, for a better future for a Black American ethnic community? What is that vision grounded in and based on? What strategies would you put forward to address the very problems you highlight as statistical truth? What tactics and steps would you take to enact the solution sets informed by said vision and strategy? If we approach those challenges from a business perspective, as you suggest, then benchmarks are certainly important. They provide a baseline for analysis and understanding.

If we view the prevalence of problems related to race in business terms, we can review a Profit and Loss statement, so to speak. Who profits from race, racialization, a racial worldview, and racism? Who loses? On balance, I argue, our entire nation, and Afro-Americans in particular, do not profit from racial ideology and its continuation. How about viewing the issue as a Balance Sheet? A company’s balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity.

From the statistical gaps and liabilities that you and many others point to as deficits in Black American life, one could say that the liabilities outweigh the assets. Your liability metrics point strongly in that direction. Yet if the liabilities outweigh the assets, why should most people who are not racialized as black even care? On what basis—if the liabilities indeed outweigh the assets—is there for investments in the development of that community? If the liabilities outweigh the assets, then we can’t blame people for presuming the worst about Afro-Americans.

From a balance sheet perspective, there must be some assets upon which we can build. I see those actual and potential assets in terms of culture.

If we apply a cultural lens to the problems we face, we can ask: What narratives, ideas, visions, values, beliefs and aspirations—plus skills and practices—can and should we emphasize and enable to enhance the material and psychological advancement of the lives and souls of black folk?

Vision incorporates values and aspirations. Visions are expressed in language as metaphors and narratives. If we incessantly tell only stories of “black” lack and limitation, deficits and liabilities, without a counter-balance which opens the frame with examples of growth and development, achievement and accomplishment, resilience and adaptability, then a disservice is done not only to our current aspirations as a people, but to our actual service to this nation for hundreds of years. Ours is not only a story of degradation.

Clifton, your reaction to my opening salvo in this symposium offered no countervailing examples of Afro-American assets. That approach exemplifies “deficit-framing” based on statistical measures. This very practice was identified 1970 by Albert Murray in The Omni-Americans as the (often unwitting) foundation of the “folklore of white supremacy” and the “fakelore of black pathology.”

We include narratives of achievement and aspiration not to ignore the existing problems, but also to address the social-cognitive dynamics Glenn pointed to in his theory of race. Our brains are hardwired to respond to threats. If we habitually and incessantly describe any group in negative terms, negative associations are the result. If we have negative associations with something, we usually try to avoid, control, or get rid of it. If we continue to stigmatize black people as “less than” in a range of racial metrics, rather than at the very least stating how far we’ve come, even considering the downsides of the last 30-40 years, the merry-go-round of racialization will continue doing its dirty work.

For instance, the poverty rate among nominally black people in the United States has fallen by almost 10% in the last 40 years, to 20%. That level is still too high, of course, but we should acknowledge the advance.

To those unwilling to question, let alone challenge, the maintenance of racialization and a racial worldview via statistical findings based on racial data collection, I ask, per Adrian Lyles, “What benefit do we hope to achieve by furthering the collection of ambiguous skin color proxies?”

The problem of gaps in academic achievement is not a “black” problem. Generations of American citizens, working within an outmoded public education system, lack access to a twenty-first-century education that prepares them to flourish as American citizens and members of a global world.

The high relative number of men identified as black in prison is not a “black” problem. The entire body politic and society should be concerned about it.

Gaps in income and wealth are not a “black” problem. Despite decreased overt racism today, we should also factor in historic domination and racism, with their carry-over and residual effects. Race should not be the primary analytic category at all. We should look at a more holistic range of factors, including family structure and education level.

For example, from a racialized perspective, there’s a wealth gap of $164,100 between “whites” and “blacks” in a recent Federal Reserve survey. Yet, as Ian Rowe details in his excellent work Agency:

According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the median net worth of a two-parent, college-educated black family is $219,600. For a white, single-parent household, the median net worth is $60,730,” a differential of $158,870 in favor of such “blacks.”

Obviously, what Rowe and others identify as the success sequence matters in “avoiding poverty, having greater household income, and achieving middle-class status”:

Completing high school, gaining

Full-time employment, before

Marriage, and, then, having

Children

If we can agree that such a success sequence is fundamental, the question becomes how to increase its adoption by those most at-risk of becoming subsumed as statistics on graphics of lack and liability. Those striving for actual solutions will ask questions such as: What policies would need to be engendered? What local educational and communal institutions supported? And what ways and means enacted to shift families and individuals in high-crime areas from violence and other maladaptive behaviors?

I happen to believe that as a people who, as Robert Woodson puts it, “were at our greatest when white people were at their worst,” that we have the internal cultural wherewithal to surmount our current challenges. But we shouldn’t try to do it alone. We need mature leaders with a generative vision for the future who will design integrative strategies that include likeminded friends and colleagues. We need leaders with an engineering mindset who will initiate social experiments to actualize such visions and strategies.

As citizens, we are like shareholders in America Inc. Let’s build equity in America Inc. by focusing not only on problems and predicaments, but solutions grounded in a shared vision, shared values, shared aspiration, and shared responsibility—all of which point to culture over the decoy of race.

Dear Greg,

Thanks for your reply. I've been wrestling with these issues for decades. We're in agreement about the negative impacts of an overly racialized society. Nobody wins, for example, when every racial group in America thinks they're victims of discrimination (see this NPR poll for details).

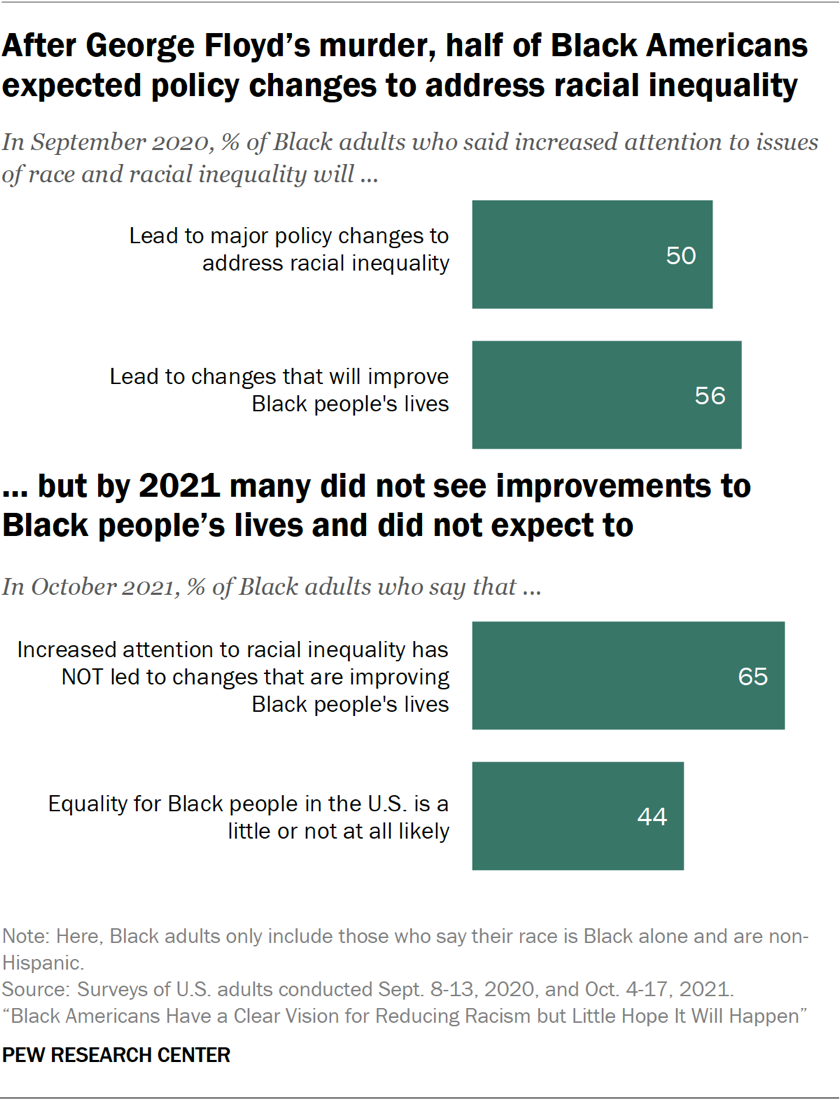

Things have gotten worse since the “racial reckoning” that began during the summer of 2020. I think we're in agreement about the need to “deracialize,” but we may not agree on how to go about it, the desired end state (i.e., how much racialization, if any, is appropriate), obstacles that will make it difficult to achieve the desired end state, or how long it will take to get there.

A majority of black folks have bought into the idea that various forms of racism are the most significant impediment to black progress. A long Pew Research analysis from August is worth a read if you have doubts. Here are a couple of graphics that show pessimism and a fundamental misunderstanding of why black progress stalled out many years ago (more on this below).

To make a long story short, Black America has mostly bought into a “bias narrative” when it comes to why black progress stalled out. In a 2019 Manhattan Institute paper, Glenn suggested that a competing narrative, a "development narrative," needs to be considered. (Here’s a condensed version of the argument.)

The bias narrative absolves Black America of any blame for the disparities I've mentioned (e.g., academic achievement gap, income gap, employment gap, wealth gap, life expectancy gap, differences in poverty rates, differences in incarceration rates, differences in criminal victimization rates, etc.). It also implies that black folks can only achieve “equality” if others acquiesce and give it to them through transfer payments and major overhauls of America's economic, legal. political, and health care systems, institutions, culture, etc. Not only is this unrealistic, it's wrong-headed. I'll give you two examples of why I feel this way.

Let's start with the wealth gap. Roger Ferguson, former vice chair of the Federal Reserve and then president and CEO of TIAA mentioned three things to close the racial wealth gap during an interview he did with Yahoo back in early 2020:

Higher incomes through education

Greater exposure to equities

Enhanced financial literacy

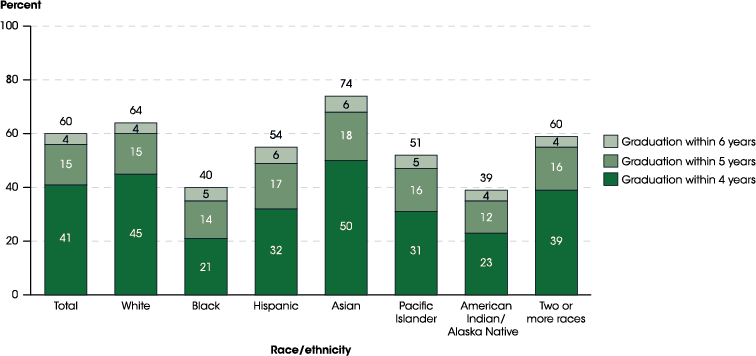

Ferguson pointed out that fewer blacks have college degrees than their peers and that black college students are less likely to earn degrees. About 21% of blacks 25 and older have a bachelor's degree compared to 35% of whites. Less than half of black college students at four-year institutions earn degrees. Here's a graphic from the National Center for Education Statistics:

Here's another graphic from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES):

So what explains these differences: bias or development? Let's look upstream. We're past the point where there are major differences in the educational opportunities available to black children compared to their peers. Per pupil spending, for example, is essentially the same for black school kids as for their white peers according to the St. Louis Fed. Their data shows that the average black student attended a district that spends $14,385 per student vs. $14,263 for their white peers. When the expenditures were narrowed to spending on instruction, the figures were $7,169 per student and $7,329 per student, respectively

Academic achievement, however, is nowhere near parity. I won't claim that everything black kids experience at school is exactly the same as what their peers experience, but those differences are overshadowed by what happens when kids are away from school.

Take a look at absenteeism and how it impacts academic performance. Here are a couple more graphics from the National Center for Education Statistics:

The graphs tell us a couple of things:

The kids who are least likely to miss school (Asians) tend to perform well on the tests

Missing days of school has negative impacts for all groups of students

Here's a US Department of Education analysis for the 2015-16 school year if you want confirmation. And here are the percentages of school children who were chronically absent by race:

Asian: 8.6%

Black: 20.5%

Hispanic: 17.0%

White: 14.5%

Overall: 16.0%

The analysis says a school kid is chronically absent if they miss 15 or more days of school. Others define chronic absenteeism as missing 10% of school days (18 days out of a typical 180 day school year) but the relative differences still stand.

I won't bore you with the details, but I have done spot checks on district numbers around the country. The same pattern plays out every place I've looked (e.g., Chicago, State of Illinois, Memphis, State of Tennessee, Fairfax County, Virginia, Arlington, Virginia, Newport News, Virginia, State of Virginia, etc.)

Some might argue that various forms of bias are the reason why black children are more likely to miss school than their peers. That feels like a stretch. It also overlooks the roles of family structures and parenting. Mothers and fathers are responsible for getting their kids to school, not society. There may be things we can do to strengthen families, but the buck stops with parents. We can't expect society to come to our homes and get our kids ready for school.

All the above suggests that the development narrative offers more opportunities to boost Black America than the bias narrative. Black leaders can huff and puff all they want, but most of the things they prioritize (e.g., criminal justice reforms, policing reforms, voting rights, etc.) won't get black kids to school and won't reduce inequality. They're a distraction from the work that needs to be done.

I don't claim to have the “silver bullet,” but Derek Neal, who was head of the University of Chicago's economics department at the time, wrote a paper titled "Why Has Black-White Skill Convergence Stopped?" in 2006. Neal's paper suggests several possible reasons for the lack of progress since the late 1980's (e.g., the potential importance of discrimination against skilled black workers, changes in black family structures, changes in black household incomes, black-white differences in parenting norms, education policy, etc.).

Many of the things Neal mentions are within Black America's control. My overall point is that we can't deracialize America as long as large racial disparities persist and the bias narrative holds sway. We need to debunk the bias narrative and convince more black people that they have agency, that the development narrative offers a path towards black progress. People like Ian Rowe and Robert Woodson talk about this all the time. Black immigrants figured this out a long time ago. This US Census Bureau analysis from 2017 (“Characteristics of Selected Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean Ancestry Groups in the United States: 2008–2012”) shows that many of them are thriving. It shows that many black immigrants exhibit high levels of education, labor force participation, and income. The prominence of black immigrants and their children at America's elite colleges and universities confirm this as well.

I can do deep dives on any of these issues if you like, but I hope I've provided enough information to give you a sense of what I think needs to be done in order to boost black progress.

Best regards,

Clifton Roscoe

To go beyond prayers and laments for the victims of urban violence, and derision and contempt for the criminal perpetrators, see the evidence-based strategies and measures of Thomas Abt, author of Bleeding Out and founding director of the Center for the Study and Practice of Violence Reduction.

It is not that we don't have examples of once maginalized groups that time and human evolution hasn't largely erased their perceived distinctions. At the turn of the 20th Century Poles, Irish, and Italians (as well as other nationalities) were painted as sub-human, lacking even the ability to live amongst white Anglo-Saxons who simply got to NY before them. Do we really make any "racial" distinctions between a Kowalski, a Benevuti or a O'Donnell?

While actors may prefere certain colors of hair and height may be favored over short stature, and slim over fat, this is moving away from "race" to lifestyle.

My parents raised me in a household where people of all races (my parents were an academic and an artist) were frequently at dinner parties, my parents' main form of recreation. Stanley Crouch and Russ Ellis were among the many people who taught at my father's college and were frequent dinner guests in my parents' house.

As close to as possible it was pounded into my head to consider national, racial or ethnic differences as tertiary characteristics, like hair color or choice of pants. Of course I didn't just grow up in my parents' home but in Southern California in the 60s, so that affected me as well.

Reaching back half a century I actually have a hard time recalling them as Black professors, as opposed to the unique and the wonderful teachers and raccounteurs both Crouch and Ellis were. Any "virtue" goes to my parents, who I now realize were simply trying to raise me in the world they hoped would be.

Now, of course, such "color blindness" is a major, maybe even mortal sin, yet at 70, and having completed my career in elective office and as a lawyer, I risk little by embracing Glenn Loury's dream.

Having seen this movie before, how can anyone think that racializing every part of society once more will work out better? Race will never go away so long as it can be exploited for personal profit or political gain, and perhaps both. We enter Black History Month with theme of resistance. Resistance against what exactly? Civil rights have largely been achieved. That doesn't mean society is perfect but if perfection is the standard, then everyone will be perpetually disappointed.

What avenues of life are blacks excluded from these days? There is no field or industry that actively shuts them out. On the contrary, one company after another falls all over itself to hire or promote blacks, often irrespective of their ability or the results. Universities have watered down standards to increasing minority admissions, which should be seen as patently insulting and a case of setting people up for failure, but instead its hailed as a step forward. Everything from math to campus honor codes to punctuality has been characterized as evidence of white supremacy, again insulting the large numbers of black people who find none of those things especially vexing.

In reading Clifton's numbers, it reflects the "bias narrative" he cites. People have been conditioned to believe that every negative outcome that a black person experiences is solely due to race. How convenient. What excuse do people in other racial groups have when things do not go their way? This is 2023, not 1923. Police brutality? If anything, police have been castrated to the detriment of the law-abiding minority residents of those neighborhoods and cities. When you ask someone how many civilians of all races are killed by law enforcement annually, the gap between the response and the facts is enormous. THAT is a narrative in play, creating an illusion of reality. I daresay this is where the argument to de-emphasize race comes from - when it become a catch-all, then it sounds more like an excuse than an explanation.

In any society populated by heterogeneous groups, some disparities are likely. They exist in homogeneous societies, too, but no one there has the luxury of substituting an immutable characteristic for agency. As Glenn has repeatedly said, American blacks are the wealthiest, most powerful, and freest people of African descent anywhere on the planet. Far from saying good-bye to race, we have plunged headlong in the opposite direction, treating it as the only thing, which is not helping anyone. We have the DIE industry, which actively participates in racial and gender discrimination, but of the sort that is deemed acceptable. No; that's not how it works. Such discrimination is wrong on its face; it does not become okay because of who the targets are.