It’s one thing to worry that the person living below you overhears you saying something politically subversive and reports it to the secret police, who will drag you into a jail cell for questioning. That is a dangerous, repressive situation. It’s another thing entirely to worry simply that the person living below will confront you about something you said that she didn’t like. This latter scenario is a feature of a free society, not a repressive one. In fact, in a free society, there’s no way to avoid this situation if you happen to hold an unpopular view—you can keep quiet and avoid censure or you can speak up and take whatever criticism comes. But there’s a vast difference between enduring the opprobrium of your peers and hearing the jackboots marching toward your door.

In this clip, Winkfield Twyman Jr. suggests that his own dissent from mainstream views on race makes him a kind of political dissident. But that’s a rather outsized claim for a rather quotidian set of political views. Winkfield puts forward two related positions here. The first suggests that racial identity is a matter of personal choice, that we can resign from it in the same way we can resign from a club. The second suggests that racial resignation is such a radical (and radically unpopular) act that it’s tantamount to political dissidence in a repressive society. But the first position negates the second. If racial identity is merely a personal choice that can be opted into or out of at will, then it has little political meaning, for it ceases to function as an historical phenomenon or a site of familial belonging. It’s just a label. And who is willing to march in the streets and risk the gendarmes’ batons—as Czech dissidents did in Václav Havel’s Prague—for such a label? What would they even be marching for?

Individuals declaring their lack of allegiance to the racial flag does nothing to address the large-scale effects of race in this country. If every single person in this country stood up and “renounced race” (whatever that would mean), we would still have the patterns of inequality and the disparities we see today. What we would not have is a language and set of affiliations that would allow us see those patterns and disparities within the long history of race in the US. That’s not something you can wish away through an abstract “resignation from race.” Maybe some day we will develop into a society that no longer requires the concept of race. But I don’t think that’s happening any time soon. In fact, we should hope it doesn’t.

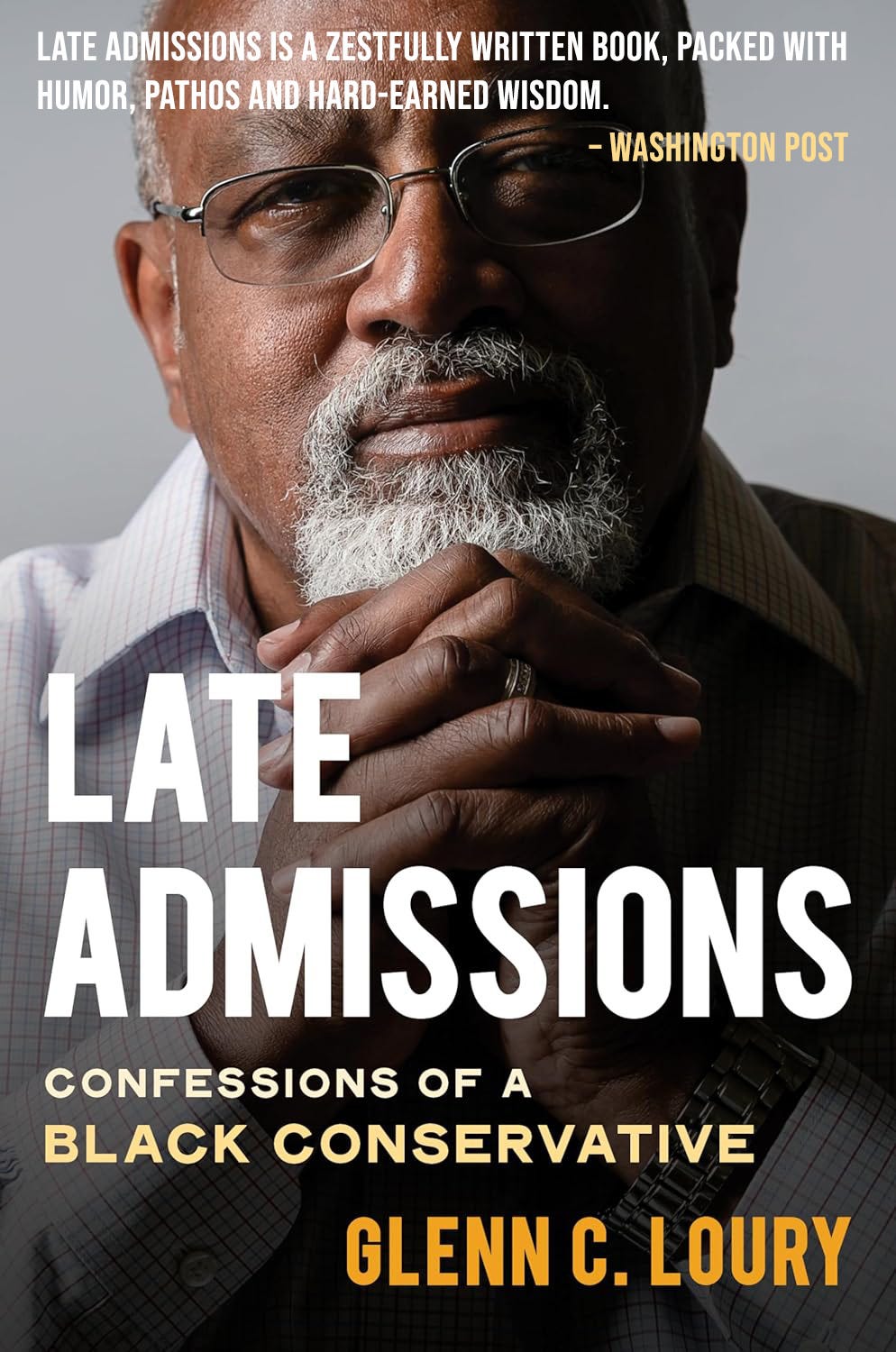

This is a clip from a bonus episode of The Glenn Show. To get early access to TGS episodes, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

GLENN LOURY: A hundred years from now in the United States of America, if you ask, “What does blackness mean?” the answer is going to be very different than what it meant 50 years ago or than what it means today. And we're going to have to work that out.

Now, I think it raises a lot of interesting questions. It raises some philosophical questions. My son is a gay man. I did come up in the AME church. We were taking the kids to an AME church for a while. And he's saying, “All those people think that I'm gonna go to hell because I'm gay.” And he's mad at them. And I'm trying to say, don't be mad at them, man. These are just some Christians. They don't mean you any harm, really. They're really pretty decent people. I agree with you, I say to him. I say to him, I agree with you about, yeah, it's okay for you to be gay. You're not going to go to hell. I don't think you're going to go to hell. But these are not bad people.

And I'm saying, look, we used to be a society where everybody was in the closet and we're becoming a society where people can just do what they want to do. Some of the people from the old school are still with us. What are we going to do, throw 'em in the dust bin of history? We can be a little bit charitable, I'm just trying to say to him.

So that's my question to you people who are getting ready to throw away race. What are you going to do with a guy like me who still wants to hold on a little bit to the narrative of his life that he wants to read through the South Side of Chicago?

WINKFIELD TWYMAN JR.: That's a great question, Glenn. I love that question. Thank you so much. I still often feel the same way. It's from a different angle. So what I was growing up, to me, blackness equaled enterprise, because I would read Black Enterprise magazine at gramma's house. Blackness was Earl Graves Jr., Percy Sutton, John Johnson, Berry Gordy, you know the whole line-up of characters.

And I was so surprised to find that people had a different definition of blackness when I entered college and law school in a larger world. And the young generation today—blackness, oppression—I sometimes feel like a dinosaur. I feel, as you suggested, time is moving by, my generational way of understanding Blackness is going to become obsolete. What do I do?

I feel that same sense of becoming more obsolete as the young generation grows up. And so, in a sense, I almost have come to the place where, number one, I just can't abide the dogma. I just can't abide the slogan words. You're never going to convince me that, that blackness equals perpetual victimhood. That's not my bag. That's not my game. That's not how I'm oriented. My neural pathways don't accept that. Does not compute.

So for me, logically, retirement from blackness is a way to retain my mental human dignity and coherence because I refuse to buy into a system that defines blackness so disadvantageously.

But don't you see, how the very necessity of “announcing your retirement from blackness” is, in a way, a tribute to blackness? Doesn't it give the category meaning, even as you eschew it?

I definitely do. Because, if you retire from working in the office or if you retire as a football coach or as an army general, you retain the muscular memory of working in the office or working as the coach or working as a soldier. So I'm not suggesting that I'm forgetting all of my muscular memory of growing up in black business, black America. It's a part of who I am.

But I do think that it's a small way I can undercut the power of dogma that I disagree with. I think Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote an essay called, “Live Not by Lies,” or something like that. Maybe that was a phrase in his essay. The point being, an individual can't change society, but the least you can do, at least in your personal life, is to make personal choices that don't mouth the lie, that don't strengthen the lie, that don't reinforce the lie, as it was, say, in the Soviet Union.

To me, I very much see the current state of blackness is almost Soviet in nature to the degree that it imposes dogma and slogan words on free-thinking people. I love Free Black Thought, for example, because people are open-minded, curious.

I got to object. I got to object. I object.

Go right ahead. Jump in, jump in.

Listen to yourself. Solzhenitsyn? The Gulag Archipelago? Come on. This is nothing like that. The massive apparatus of the state employed to suppress millions of people across the continent based on an ideology that has death camps at the end of the tale is nothing like this whatsoever. And the fact that you would invoke that analogy is indicative of hysteria. The question becomes, why does the question of race engender such hysteria? That's a question about you, not about race. The Gulag Archipelago? Come on, man. Come on. Totalitarianism? Death camps?

Can I reply? Here's my answer. Thank you for that vigorous critique. I appreciate that. In the law, we always recognize that one can make an argument by using the most extreme examples of something to discredit it. You have done a great job in suggesting that these manifestations that I allude to are not real and they're overblown. I think that is true. I think those examples are certainly not examples we live with today.

But if you dig deeper, Glenn, if you dig deeper into what I'm getting at, it's not the external manifestations of the camps and the state system. It's the smaller, more personal things that the author of “The Power of the Powerless” wrote about the writer, the playwright from Prague.

That was Václav Havel.

Exactly. Exactly.

I love that essay. I love “The Power of the Powerless.” But go on.

Yeah, sure. And one of the things he suggests is that during that system, people would mouth certain phrases or slogan words, “workers of the world unite,” and they would watch what they said. And that was the mindset that allowed the system to continue.

Similarly, I suggest that among those who are non-conformers, there's an increasing desire and sense of watching what you say in certain circumstances. Notice the two or three times in this conversation where I've looked to the side and lowered my voice.

Notice the background. Do you see the wonderful background? That's [a picture of] the Brooklyn [Bridge]. I don't usually sit here, Jen will tell you. I usually sit for podcasts in my regular place with all of my diplomas. So why do I sit here for this podcast? It's because my normal place is above my family member who's home for the week. And I know my family—Jen's laughing—I know my family member's perception of my opinions. So I was forced to have this podcast here because of that desire to respond to the dogma and slogan words of someone else.

If that's not the beginning of the bad place, what is the beginning of the bad place?

So you had insinuated earlier in the conversation that you were in a Soviet whatever. And I interpreted that to mean that you didn't want to be overheard by people sharing space with you who might disagree, because you knew you'd be judged. You knew you'd be held to some kind of account.

But I'm sorry, I'm not sure you're appreciating my point. I loved that essay of Havel. To live within the truth, to not be complicit in the reproduction of the lie, the green grocer puts the “workers of the world unite” sign in the window because he just wants to get along. He doesn't want the party apparatchik coming around saying something. And the lady who's getting her vegetables sees the sign and doesn't say anything, but she knows it doesn't mean anything. It's all a fraud and everybody is complicit. And that's a small illustration of a larger thing that makes the system go. And it's a system of lies.

Now, the experience of race in American life, is it a system of lies? Is it a compromise with the devil? Is it a surrendering of our soul? Is it a “flowing along with the crowd down the river of pseudo-life”? That's a quote from Havel. He says that's the power of the powerless. The power of the powerless is they're prepared to say the emperor has no clothes. They're prepared to live within the truth, come what may. And is race that?

I don't think so. Frankly, I don't think so. This is my argument. Coleman [Hughes], he says “The End of Race Politics.” And then he says “Arguments for a Colorblind America.” How did you get to the politics? I get the idea that here's a woman. I love her. The fact that she's not black should not impede me from making a union with her. I get the idea that I shouldn't live in a box. I get that. How did you get to “the end of race politics” from the personal claim that racial identity is a heavy coat that I choose not to wear, I choose to take it off?

Politics? That means mass incarceration. That means urban ghettos, and what are you going to do about it? That means how do you interpret the 14th Amendment, given the history of this country? And so on. That means who's the mayor of Chicago? That means what's the tax rate?

There's no race politics? I can't take race into account when I'm talking about politics? You never demonstrated that. You asserted that. You asserted that on the basis of a relatively narrow and I don't think all that profound claim, which is that when I go through life, I shouldn't let race be that much of a determinant of who I am or what I do.

The country still has the history that it has. You didn't elide and erase that by your personal flame of liberty. I wish not to be encumbered by the raciality of society. Therefore what about politics? Not very much, as far as I can see.

Race is a lens. Race is a filter. We can choose to use that lens, apply that filter ... or not....in the same way we can choose to embrace & apply any other particular demographic qualifier: I am short, I’m tall, I’m Jewish, I’m an Atheist, I am a New Yorker, I’m a Bears fan, I’m straight, I’m gay, I’m Black, I’m White, I’m Heinz 57... the list is endless.

Glenn, however, suggests that if that were true. ..."If racial identity is merely a personal choice that can be opted into or out of at will, then (RACE, per se, would have) little political meaning" and would ‘cease to function as an historical phenomenon or a site of familial belonging.’ He tells us that if this were actually the case, then ‘wearing’ race as an identifier (or not) could not possibly be seen as a 'radically unpopular act' (the equivalent of political dissent).

But this is simply untrue.

In fact there are any number of personal identifiers that we can put on or take off at will (like that heavy coat they mentioned) whose use or non-use may very well have significant political/cultural/personal consequences for both the user and his surrounding community.

Prior to October 7th and the terrorist attack by Hamas, the personal choice to publicly identify as Jewish (meaning to do so in such a way that ‘everyone knows’ you’re Jewish) probably carried minimal significance...and minimal risk. Post 10/7, to wear the Jewish faith as a personal identifier, linking the ‘wearer’ to both the historical phenomenon of Judaism & the at-large Jewish family is to risk, in many cases, personal assault & death. It’s still a personal choice...but it’s a choice which is weighted with potential consequence.

Unlike faith, which tends to be invisible, race is not. But if race is all we see...if race becomes our primary filter...if Race is who I am, first & foremost, then everything which happens to me, happens because of THAT single thing: Race the hammer in a world filled with Racist Nails. As in that now infamous Michelle Obama story told by Tim Constantine: standing in line at an airport, waiting to be processed, a man cuts into line in front of her. Equally, Tim, standing in line at a different airport, at a different time, sees a woman cut into line in front of him. Michelle sees the line-cutting as a racist act; Tim sees it simply as someone being an a**hole. Which explanation makes more sense?

Glenn suggests that even if “every single person in this country stood up and “renounced race”, we would still have the patterns of inequality and the disparities we see today. And this is true. But he goes further and says that such a renunciation would somehow eliminate the “language and set of affiliations that would allow us see those patterns and disparities within the long history of race in the US”. But Why? How could this be true?

The personal choice of any given individual to identify or not identify with any particular demographic impacts only that individual. That choice does not affect our ability to continue to use that demographic identifier to categorize populations or population histories over time. How could it?

Let us assume that no one in the world now identifies as a Nazi. Let us say that every single person’ stood-up, right this very instant and ‘renounced Nazism’. We would still have the patterns of hatred and homicide that characterized Nazis. And, of course, we would still have the language that would allow us to see those patterns within the long history of political movements in the West and the horrors which were WW2. One does not preclude the other.

What a renunciation does do, however...what does happen when ‘every single person’ chooses to refuse the ‘Race’ coat...is that a socio-political door which has been nailed shut for decades, cracks open. In fact the refusal removes a filter that prevented us from seeing a series of harsh & unpleasant truths.

“Why did Joe not graduate from High School?” Occam’s Razor’s judicious use might tell us, Joe didn’t graduate because Joe didn’t study....because Joe can’t write a sentence....because Joe can’t handle arithmetic....because Joe skipped class....because Joe got free passes K-8. That Joe may also be Black is irrelevant except as a demographic qualifier.

If 80% of all non-graduates were Black, we might well ask what is it about the Black experience, the Black family, the Black culture that somehow works against scholastic excellence, but again, the results are owned NOT by the population which shares a color, but by the individuals (like Joe) who failed to study.

Once we know, once we can prove, that systemic racism has been eliminated...that there are no color-based barriers that prevent Joe from attending school, acquiring text books, sitting in class, going to the library....that there are no laws that forbid X,Y, or Z because of Race...that there are no jobs that Joe can’t have because of skin tone.... that the test that Joe failed is not race-centric....then Race as a Personal identifier truly becomes something which is as trivial as height, or weight, or shoe size. The responsibility for Joe’s failure lies with Joe...and perhaps Joe’s family. They don’t lie with a skin color.

100 years from now the answer to the question, 'What does Blackness mean?' will indeed be different from what it was 50 years ago. But that difference must start now.

"Maybe some day we will develop into a society that no longer requires the concept of race. But I don’t think that’s happening any time soon. In fact, we should hope it doesn’t.'

My gosh! Really? We should hope that society never evolves to the point where people do not judge others by the color of their skin, where they were born, or who their parents were?

I greatly appreciate you, follow you on social media, and have learned from you. I am not sure what you're hoping for here. I would think the best place for society to evolve is that we are all homo sapiens — male and female humans—and the best attributes of humans move us all forward.