In this part of my conversation with Jennifer Richmond and Winkfield Twyman Jr, Jennifer tells a story that I imagine is quite common. A black woman at her church has beautiful hair, and Jennifer wants to compliment her. After all, the woman has probably gone out of her way to make her hair look beautiful. Why shouldn’t she be complimented? But Jennifer, a white woman, fears that her compliment on the beauty of the woman’s hair will be misinterpreted as a disguised comment on the woman’s race, and awkwardness (or worse) may ensue. My first thought is to tell Jennifer that, since her motives are pure, she needn’t worry about how her words will be interpreted. But that is naive advice, for such a compliment coming from a white woman does indeed risk giving unintended offense, no matter how much we all might wish it didn’t.

Jennifer’s dilemma illustrates the core conundrum of colorblindness in miniature. That is, she wants "race" not to matter when complimenting a black woman on her beauty (or intelligence, or punctuality, or discipline, etc.) And yet, the racial subtext of such a remark is unavoidable. Jennifer's innocuous intent on its own is not sufficient to exempt her from the constraints imposed by the enormously complex web of racialized meanings which American social history has, over centuries, bequeath to us. Neither can personal declarations of racial self-definition circumvent the subtleties of perception and interpretation that attend even our most casual social interactions.

A “white” woman expressing wide-eyed wonder at the beauty of a black woman's hair runs the risk of becoming a fraught encounter. If Jennifer could communicate her intentions unfreighted by the weight of our racial history, she would have nothing to fear. But she cannot speak outside of the flow of history and the web of culture. None of us can. In theory, I might try to “absolve” her of any wrongdoing, as a black man, by confirming that she is not a racist. In reality, the so-called “black card” is non-transferable. There is little that any one person can do to change this state of affairs. That should not stop those who wish for a different racial reality from working to bring it into being. But we should not confuse the desire to change our social reality on matters of race for reality itself.

This is a clip from a bonus episode of The Glenn Show. To get early access to TGS episodes, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

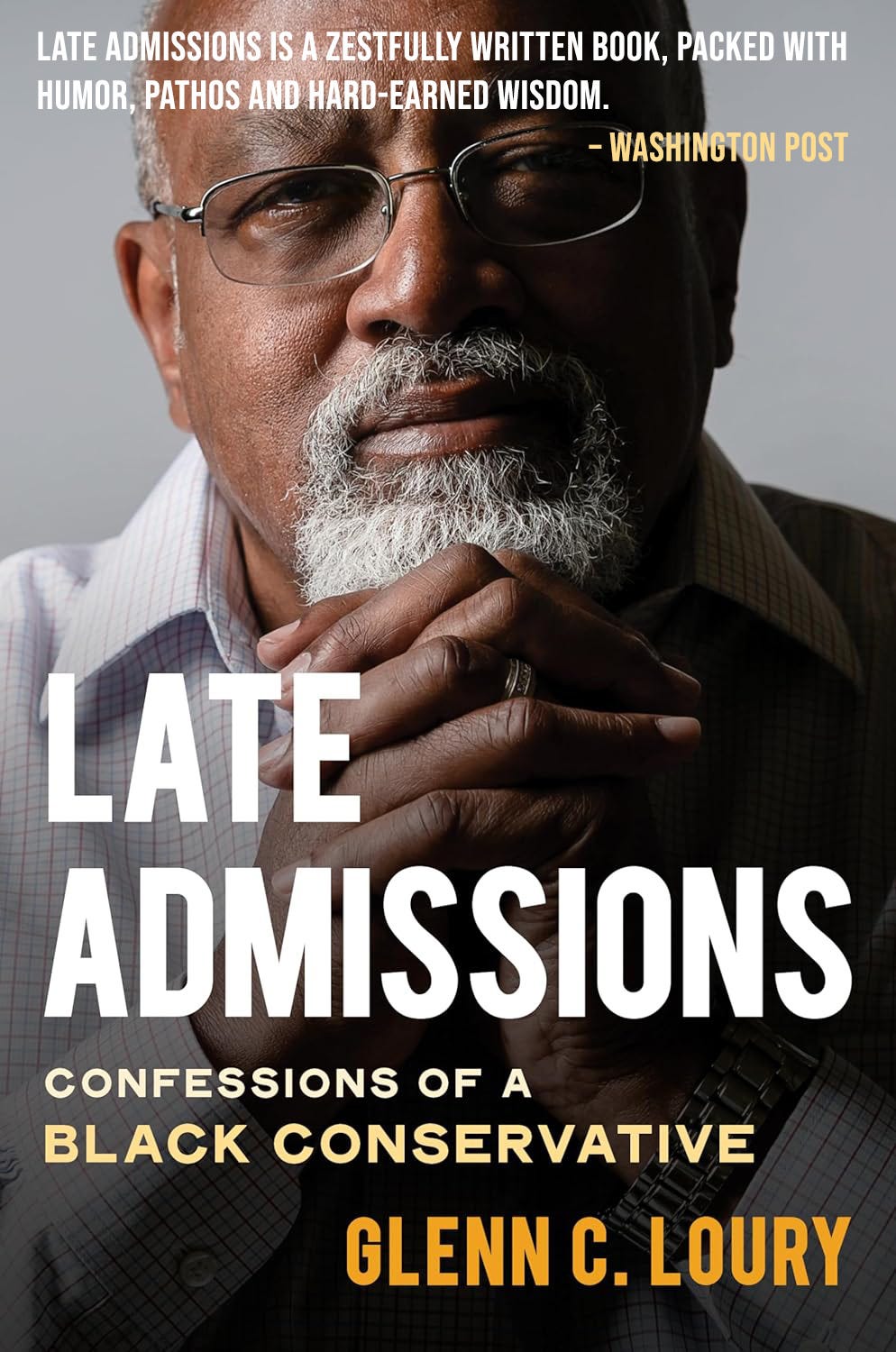

JENNIFER RICHMOND: We're talking about language, and Glenn just mentioned, why aren't we having these conversations? Who are the people to bring them up? Glenn, you mentioned in your book that your own race has something to do with how your comments are received. I'm going to quote. You say, “While conservatives who called out the BLM rioters found themselves accused of racism, such charges would not stick to me."

This is a question that Wink and I grapple with in our book. As a matter of fact, at one point, Charles Love lovingly called Wink my “black filter.” It's a silly anecdote, but a woman in my church had beautiful hair. And I was so afraid to tell her that her hair was beautiful, because then it would be seen as a white-black thing, whereas her hair was just truly beautiful. And Wink laughs at me. Charles Love laughed at me.

But I feel like there is, in having these conversations ... I don't know. I have a voice, and if I'm doing this truth-telling alongside Wink or even on my own, how can I have these discussions? Will I just be dismissed and replaced? Like you mentioned, you have a voice, it'll stick. I do have that voice, and I don't know how it carries.

GLENN LOURY: Jennifer, you expect me to solve a problem that is baked into the cake. I actually wrote about this. I have an essay on self-censorship from the 1990s. It's actually going to be reprinted in a updated version. They're going to make a small book. Polity Press is going to put it out in the spring of next year, “Self-Censorship in Public Discourse.”

Anyway, the long and short of it is there's no such thing as free speech. You can be free from the restraint of the law in response to what you say, but you can't be free of the fact that people, when they hear what you say, will form whatever opinions about you that they will form. And you can't be free of the fact, in the case at hand, that you're white. In a discussion about race, you'll be seen as a white person saying this or saying that. And you're asking me to somehow relieve you of the impediment or the burden, anticipating that people will take your whiteness into account when they hear what you say, and perhaps to your discredit, which you regret. And I regret it. But it's baked into the cake.

Can I give you cover? Yeah, I can give you cover. I can say, even a black person would say the same thing that you're saying, and that would allow you to feel a little bit more protected in saying it yourself. This is, by the way, my argument with the young Coleman Hughes. He has a book out, The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America. People should read the book. And I like Coleman. I think he's smart. But there's something that I find disquieting about the book.

So in the book he says, you have the antiracists. But the antiracists are really the racists, and that the real antiracist was the Martin Luther King, “I Have a Dream” antiracist. I'm not going to do a whole exegesis on Coleman's book, but I think that's overly simplified. I think it misses something. “Blindness.” These ideas need to be interrogated. Of course, he doesn't mean literally you don't see race. Then what do you mean? He says it shouldn't matter with respect to how you conduct yourself in private and public life, but obviously it does matter.

WINKFIELD TWYMAN JR.: I think that's a great idea to chew on for a bit, colorblindness. Because Jen and I had talked about that earlier before starting the podcast. And I love Coleman Hughes. I love his non-conformity, his independence, his deep logic. I love the guy. But I probably wouldn't have chosen that as a title for my book, because as you suggest, it invites the natural critique. Because we can all see color. Even those who aren't moved by color can see color.

Where should we be headed, if not colorblindness? Suppose colorblindness is incoherent, as you write in your book. I just wonder, what is the yellow brick road at this point? How do we get to a place called Oz in the land of race? So I, for example, have chosen the path of just retiring from blackness à la Thomas Chatterton Williams and Adrian Piper. I read Thomas's book, [Self-Portrait in Black and White:] Unlearning Race, and I was persuaded. And particularly when I read about Adrian Piper's account of deciding just to hang up her black shingles that appealed to me as an individual.

Sheena Mason, who Jen and I know, has talked about “restlessness” as the yellow brick road towards the better place. Angel Eduardo has talked about “color-blah.” I probably would prefer the word “color indifference” as opposed to color-blah, but it's essentially the same thing. The question is, if we live in a color conscious world—and I would agree with that—should color indifference be the aim, the yellow brick road? And do we just simply go wrong when we conflate blackness with the political? Because blackness is more than the political. It's the human condition. It's how you love a distant cousin who's cute, it's how you worship together at the table over Thanksgiving dinner, it's zoning out on a Star Trek marathon. You can be black and do all those things, and none of those things are political. What's the aim? What's the yellow brick road, if not colorblindness?

Okay. This is an important question for me. Because, as you know from the book, I'm embedded within a narrative, reading my own life through the lens of being a black man. And yet we're embedded in the flow of history, and it's not a static situation. The dynamics are trending, I think, toward racelessness or less racedness than had been the case in the past. I think there's no doubt about that. It's fluid. The margins, intermarriage, identity things where people are making claims—“I'm black, I'm white”—and then who's going to adjudicate that.

There's a lot of interesting stuff that's going on in the interstices. Thomas Chatterton Williams's mother is white. His father is black. The mother of his children is a French woman. She's white. He's looking at his daughter and, saying, “Are we really going to impose these binaries on this child? This doesn't make any sense whatsoever.”

OK Glenn. I get where you're coming from, but it seems to me that we can't move forward towards a society in which "race" and the weight of history don't limit our ability to trust in each other's good intentions unless we are willing to risk potentially fraught encounters. Perhaps it's corny, but I don't see any other way to build a better future except through one genuine conversation at a time even when it is difficult and when our good intentions may be called into question. It isn't so much a matter of color blindness as it is committing ourselves to look at the person in front of us at the moment as they are and sharing with them our honest thoughts, emotions, experiences, etc. while remaining open to theirs. Someone needs to walk across the aisle, offer their hand and make a joke risking that it will fall flat or even cause unintended offense. The hope is that more often than not we will manage to connect on a basic level and walk away from the encounter feeling good about ourselves and our new aquantance. What else is there that we can all do?

"Terence, this is stupid stuff".

And if that's too harsh, let's just say 'silly stuff'...or normal stuff....or 'what else is new' stuff.

What we are talking about here is simple human frailty...the natural tendency of human beings to err, to misunderstand, or misinterpret what it is they see or hear as what they sense is passed, inevitably, through their own idiosyncratic filters. Those filters color outcomes. They nudge our understanding left or right, good or bad, according to our own fears, desires, and biases. We see through a glass darkly.

And if, what we see, offends us – and we’re 5 -- we cry & complain: "Charlie 'bit' me!", or "Charlie hurt my feelings"! But then Mom shows-up...gives us a hug & kiss, and makes it all better! We laugh, and return to the Sandbox to play some more with that villain, Charlie.

In the Hyper-Sensitive Now, though.... If we're 25...or 35....or more... and our feelings are hurt by some grown-up Charlie (playing in a totally different sandbox) .... we pout, & point & yell, "Microaggression!" Or sometimes, "Racism!" Or sometimes "Sexism....or Classism....or Ableism... or Misogyny!" And in this down-the-rabbit-hole, World of Woke there is no ‘kissing it & making it better’, there’s only outrage, retribution, cancellation, apology tours, punishment, and – if we’re lucky – the chance to go to ReEducation Camps, make confession, and ask for forgiveness from a roomful of Charlies.

The fear of the New Gestapo, knocking at our door, keeps us all silent.

“I was so afraid to tell her that her hair was beautiful, because then it would be seen as a white-black thing.” So what?

The question is: Are we all 5 again?

Or do we simply assume that the Other is always 5...and will cry and complain and demand retribution if – in any particular sandbox – their feelings are hurt by some invisible something they’ve imagined?

Do we really want to live in a world in which everything we say or do must be second-guessed, avoided, or muted for fear of tender toes?

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

Sometimes a compliment is just a compliment.

And sometimes we really should grant to the Other the very real possibility that they, too, are an adult and long past the outraged tantrum stage.

What then are we to do?

Speak honestly. Speak forthrightly. Exercise some common sense. Be courteous. Act like a gentleman. Act like a lady. Expect to be treated accordingly. Avoid conniption fits. Treat people with dignity (as you yourself would like to be treated). Be kind. Be generous. And please feel free to grant the Other the benefit of the doubt, as you would hope they equally grant you.

And if some idiot, in a huff, then decides to attach some abstruse & insulting meaning to a compliment....a phrase...a look...a gesture...a question... If some idiot insists that your words contain a meaning that is not there, that was not intended....then that is their idiot problem, not yours. Laugh, shake your head, ignore them and walk away.

It’s long past time we all grow up.

And being grown-up, if someone tells us, “Your hair is beautiful!”, just say “Thank-you!”. It’s really pretty simple.