The statement about the Gaza War I posted on Sunday and my subsequent conversation with Josh Cohen about the same subject have both, as I expected, generated a lot of responses, both in the comments section and my inbox. One of the least expected responses I received was from the organizers of the lecture series at the Palm Beach Synagogue where I recently gave a talk in which I pointedly didn’t discuss the Gaza War. My reticence to speak about it, and the shame I felt over that reticence, was one of the major motivations to writing the piece in the first place. And yet, when I sent them a pre-publication draft of the essay, they responded by saying, essentially, there was no reason to worry, that I could have said whatever I wanted about Gaza, and that they would have fully supported my decision to do so.

I was afraid that, if I spoke critically about Israel’s conduct in the war, my audience would infer that I was an enemy of Israel or the Jewish people. But I failed to consider that I was making an inference of my own, which is that the audience would actually make the inference I was afraid they would make. I had not thought about the range of responses I might have received. Some may have disagreed but done so in the spirit of productive discussion rather than vituperation. And hey, maybe some of them would have simply agreed with me!

I now doubly regret not speaking my mind on that occasion. I regret it because I held my tongue rather than speaking forthrightly about a pressing matter of public concern. But I now also regret it because I may have inadvertently shut down a rich, interesting, good-faith conversation before it started. Perhaps someone in that audience felt the same misgivings about the war that I do but was afraid to speak up for fear of offending her friends. Perhaps someone wanted to debate the issue with an interlocutor she could trust was, whatever their differences of opinion, a friend to her people.

As Josh points out in this clip, by not saying anything about Gaza, my self-censorship most likely led my audience to infer, if they thought about it at all, that I had no criticisms of Israel’s actions. And when those of us who have these misgivings while at the same time supporting Israel’s right to live in safety elect to keep quiet, we leave the anti-war position in the hands of extremists I have no power to affect what’s happening on the ground in Gaza or anywhere else. But I can help to draw a clear line between principled criticism of the war and antisemitism. The only way to do that is to keep the conversation open rather than shutting it down.

This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

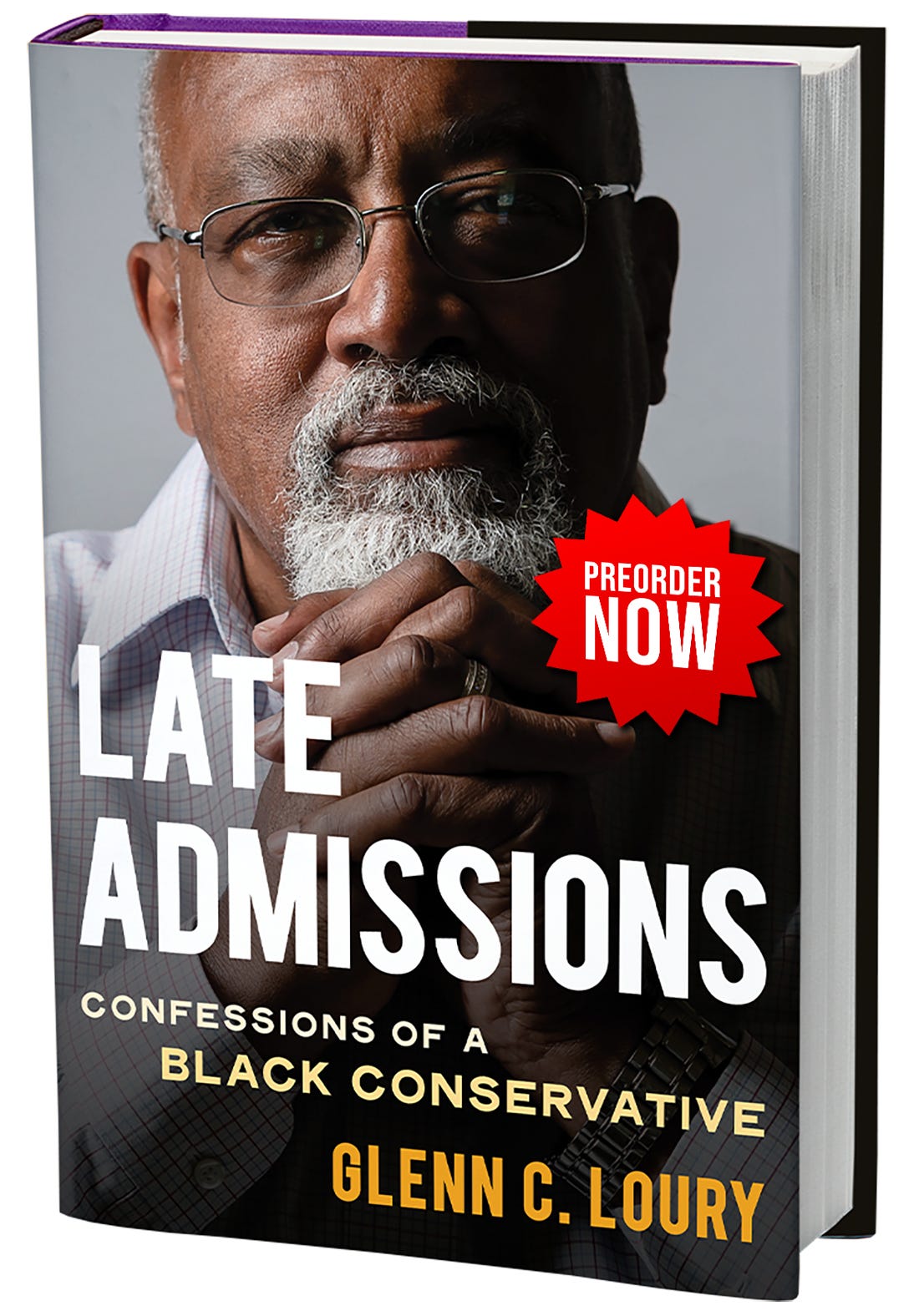

GLENN LOURY: This talk that we're having now will go up for subscribers on Monday, the 3rd of June. On Sunday, the 2nd of June, which is tomorrow, I'm going to post the memo that you saw from me in which I reflect on my experience at that synagogue and related questions about the atmosphere that we're in for voicing opinions about the conflict in Gaza and how it is to some degree taking your reputation in your hands to pretty much say anything about it—one side or the other will condemn you for this or that—and the incentives that creates to just trim your sails and not say what you think and how I find that to be unacceptable and so on. So I make something of a declaration in the statement that was posted on Sunday.

People will be hearing us talk about it. You've seen the statement in advance. The talk was in January of this year, but the invitation came months before October 7th of 2023. The topic set for me was to address whatever happened to the partnership between Blacks and Jews—that's Americans. And I did address that subject. But I did not say anything about the conflict in Israel and Gaza—and I regretted that I didn't—but didn't because I didn't want to say anything that might offend the sensibility of the congregation.

JOSHUA COHEN: Yeah, I read the statement, and I agreed very much with what you said about the conflict in Gaza. But then you mentioned in the statement that you didn't say anything, you didn't express these views of yours, and that afterwards you felt ashamed by that. That was the word you used, was “ashamed.” I was really surprised to see that you expressed shame that you hadn't said anything about it. And I did actually watch the talk.

I'm not used to giving speeches in synagogues, although, many of my best friends are Jewish.

I have to say that after I watched it, I understood better why you felt a sense of shame. And I'm saying this with nothing but affection and admiration. I'm not being high-minded about it, but I understood better.

Tell me why.

The talk is about, what happened to the relation between blacks and Jews? And there's a very nice and moving opening by Paul Lyon [sic], who, along with his wife, funds these events. And he talks about growing up in the Bronx, in a community that was like 99.9999 percent Jewish.

Excuse me, that's Paul Levy. I just want to correct the record. His name is Paul Levy.

Paul Levy. Sorry. He talks about the commitment—born in ‘47—the memorable commitment of people in this community to civil rights. And then relations get more complicated. So then you are talking about two sources of this fractured relationship between blacks and Jews in the United States. The first—I was familiar with your views about this—about affirmative action and DEI and quotas and the unease among a bunch of American Jews, including progressive Jews—Michael Walzer, for example—about affirmative action.

Affirmative action has led to a situation where large numbers of middle-class, educated, upwardly mobile, racially conscious blacks have been thrust into the highly competitive academic and professional environments in which Jews have flourished for decades, and in which Jews are vastly overrepresented in such competition. Blacks often fare poorly.

And then the second source is Israel-Palestine, points to what I see as the other principle source of our current difficulties, what might be called conflicting nationalisms among Jews. The political ideology of Zionism has given birth in the Middle East to a new, specifically Jewish, nascent state, continuing to live in conflict with its neighbors, but representing a beacon of hope and a source of identity for all world Jewry.

I thought, oh, okay. And I'm going to simplify this. Israel you present as an outpost of the West in a tough neighborhood. You don't say an outpost of the West as in “settler colonialist,” but it's an outpost of the West, which is something that you affirmatively identify with. And then you talk about a sensibility, particularly maybe prominent among black intellectuals or elites in the United States, which is a kind of Third-Worldist, anti-colonialist sensibility that leads to an identification of the black struggles in the United States with anti-colonialist struggles, and that leads to an identification with the plight of Palestinians. Is that a fair?

That's very fair.

At no point in the talk did you express any misgivings at all about the conduct of the war, which in the memo you describe as not a genocide but uncomfortably close to it.But you didn't say any of that in the thing. And then I thought, if I'm in the audience there and I hear what Glenn Loury is saying with characteristic eloquence and intellectual power, and there's nothing about that, what I think I would come away with from that is that you have no criticism of the war.

So the self-censorship wasn't just, “I'm not gonna talk about this.” The self-censorship, I think, probably left in the minds of a bunch of people in the audience, the thought, “Oh, I see Glenn Loury agrees with us about this.” I'm making a presumption about the people in the audience that they would resist the views that you express in your memo about this being a horror and it has to stop and it's a near-genocide.

And then—this goes back to your wonderful 1994 paper about the consequences of self-censorship—which is what that does is leave the people who are expressing the views that you have about the conflict, it leaves that in the hands of people who are more hostile to Israel, in some cases maybe more plausibly accused of being antisemitic than you, which is a theme in that beautiful 1994 paper of yours about political correctness.

So I thought the reason that you're ashamed was that you talked about the topic and didn't say anything about this thing, and that self-censorship may well have left a misimpression in people's minds that you agreed with them and that the only people who really disagree with them are people who are not in any way aligned with their values and concerns. Is that fair?

I think that's an astute observation. It fits well with the logic of my argument in that essay, which is basically a signaling argument. People don't know what you think, but they come to conclusions about what you think based on what you say. And if the people who have complex and nuanced views—which include perhaps criticism of Israel's conduct of the war in the case at hand—don't speak, then the only ones who will be engaged in that criticism are going to be people with relatively extreme views that are not necessarily creditable.

But that then makes it even harder for anybody who has nuanced views to speak out, because they'll be identified with the extremes, and that becomes an equilibrium. That kind of thing. And that certainly is part of it. I have set myself up to have a colloquy with the congregation about this sensitive matter, but I blinked or I choked or I held my tongue. Part of the shame comes from knowing that's a socially unproductive way to conduct my office as a social critic. But part of it comes from knowing that the motives for my reticence were ones of concern that I'd engender a backlash in certain quarters that would be unpleasant or even harmful to my professional and personal [life].

I go to a dinner party and my friend—I won't name my friend who is Jewish and who is a fervent Zionist and there's nothing wrong with that. Some of my best friends are Zionists. And I don't talk to my friend about what I think about what's going on in the interest of avoiding conflict and damage to our relationship. But what kind of friendship is that? We can't actually talk about these matters? And he gets not to know that his dear friend whom he admires for many reasons may disagree with him about this or that and the tension of that disagreement is potentially productive and maybe even nurturing of the friendship in the long run but it has to be tested and it requires courage. And on that particular occasion I did not exhibit the courage that I thought was called for. I was ashamed of that.

What do you think you could have said in that context? Because there's a related set of issues here about the nature of this kind of presentation. It's not just a profession of faith. This is what I think. You're trying to engage people and they think similarly in some ways, different from you in other ways. You're engaged in an act of public engagement and discussion, not personal statement of faith. So what do you think you could have said?

Okay. Look, I'm your friend, not your enemy. I have great admiration for the project which is manifest in the establishment and of the state of Israel and the aspirations of the Jewish people. That is coming with a cost. It's a political problem for which there's only a political solution. Even people like me, who are basically on your side, chafe and recoil at the cost that's being borne by people who really didn't do anything to deserve it. And you need to know that—again, notwithstanding basic affiliation and affirmation that a person like me would want to make—some of us are having qualms here. And more than qualms. Some of us are recoiling in disgust at what we see and some of us are losing faith in the integrity of this project that we admire and that is historically an imperative.

And the politics of this situation needs to move. Two-state solution, whatever you want to call it. But there's got to be some space given to the humanity and the legitimacy of the aspirations of the Palestinian Arabs who are under your dominion. I'm in your corner, but not uncritically, not without reservation, not without qualm, not without a sense of foreboding that you're on a slippery slope to a very bad place. Something like that.

Yeah. And here's what I think is complicated and interesting about this and about the nature of public discussion, public engagement, which is what you just said is not that different from the kind of things that Tom Friedman has been saying. Senator Schumer says Netanyahu should step aside and, among other reasons, Netanyahu should step aside because there is only one plausible solution to this, which is a two-state solution, and Netanyahu is opposed to that.

So in the moment, in this situation, there are those kinds of things. What is it about this issue or your circumstances or who you are that led you to think, “I can't go there. And I can't even invoke these [ideas]”? And I'm asking this partly because I feel a lot of reticence on this issue. I don't have an expert knowledge of it, and I am more cautious and hesitant than on other issues. I'm looking for help here.

Let me just say for the record, I've communicated with the organizers at the synagogue which invited me to give that address. I appreciate that you took time to listen to what I had to say there. I shared with them the statement that I posted Sunday, the 2nd of June about this whole matter.

And they said, “Man, I wish you had spoken your mind. No problem. We don't expect everybody to agree with everything. No problem. And if you want to come back and have a debate with, oh, Douglas Murray or some other prominent pro-Zionist voices about this matter, we're happy to invite you back, to host that debate, and let the chips fall where they may.” They said, “What are you worried about? It's okay, man. It's okay.”

So now I do have to acknowledge that some of my sensitivity about exposing myself as I have just done and as I do in the statement that we put up on the 2nd of June ... yeah. Some of my sensitivity comes from reading the comments at my newsletter and in my Substack when I had John Mearsheimer on. Of course I had him on and he was talking mostly about Ukraine, not about Gaza. But he's been very outspoken about Israel-Gaza, and he's not a friend of the current Israeli government or of the Zionist project. I think you'd have to say that about Mearsheimer.

He thinks Israel is in trouble. He thinks it's dragging the US down in terms of global opinion about what's going on. I had Omer Bartov, the historian—you may not know him, but he is a historian of the Holocaust, he's an Israeli, and he's been very critical of Israel's conduct of its relationship on the West Bank and Gaza.

And then the feedback that I get in the comments of people who are tearing into me and who have a long list of voices on the other side. “Glenn, I would wish that you would do this or that.” And it makes me feel like this is a third-rail type issue and I'd be best to avoid it altogether or to sit back and let the two sides have at each other and not to have any opinion whatsoever.

I don’t know if you read the comments, however, I have a different take on the conflict in Gaza. My viewpoint is shaped by two book I read in the past year. The first is William Schires 1961 book The Rise and the Fall of the Third Reich. The Second book was Flags of our Fathers, which was about the American assault on Iwo Jima.

In the book about the Third Reich the author points out by the time Hitler took over Germany had recovered from its defeat in the First World War. It had the most elite academic system in the world. The Doctorate was invented in the German University system. By 1930 doctoral students were already writing dissertations about how to develop mass killing systems and how to systematically remove gold from the teeth of corpses. By 1935 Jews were excluded from the Universities as student and instructors.

In Flags of our Fathers the author discusses how the Japanese military took over the country in the 1920’s and controlled all aspects of education. Children were taught to hate Caucasians and others and were drilled in military type schools.

The only way to defeat these foes was to completely crush them and then occupy them and re-educate them. That is what MacArthur did in Japan and what the de-nazifaction program did in Germany.

Israel is facing the same situation in Gaza. Hamas has to be crushed and the population needs to be re-educated. The population has been brainwashed into thinking they have no agency and if the Jews were destroyed their lives would magically improve.

Just my thoughts

I made a rather long post on Sunday. I hope the following sentiment was not lost: I have listened to hundreds (literally) of hours of Glenn podcasts and read so much of what you’ve written over the last decade, and I will continue to do so as long as you keep putting them out. I disagree with your opinion on Israel/Gaza, but I genuinely think you’re a national treasure. That sounds dramatic, but I mean it. I’d work hard to persuade you on the current situation in Israel because I value your opinion and your voice, but either way I would leave knowing you are an open, honest and brilliant voice, and a friend to Jewish people and all honest people of character. Please keep doing what you’re doing. Most sincerely, Cliff