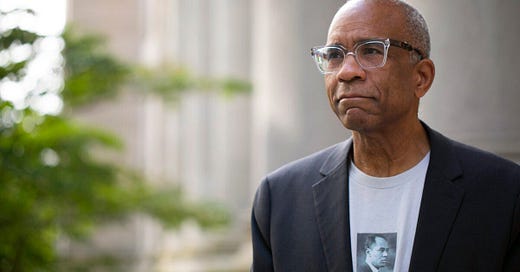

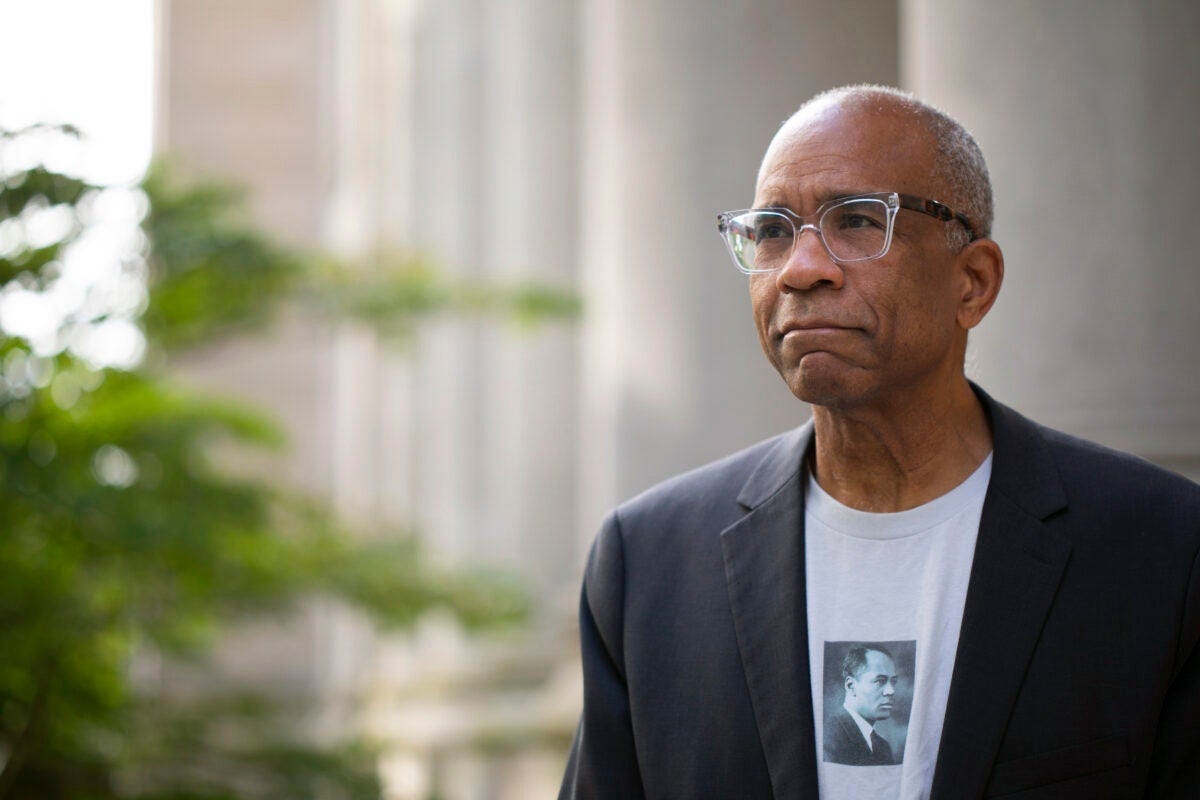

This week, I’ll be participating in a debate on affirmative action with the distinguished professor of law Randall Kennedy at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts. This won’t be our first meeting on the debate stage. Randy is a friend, and we go way back. Both of us were young professors at Harvard in the 1980s, so we’ve been having these conversations for decades. (You can watch our most recent conversation here.)

In preparation for our meeting at Holy Cross, I dug up a transcript of a previous debate Randy and I did back in 2020 on racial equality, that time under the auspices of the economics department at Brown. Despite the fact that Randy and I ostensibly occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum, as debates go, this one was not particularly contentious (although we have our moments). Perhaps it’s surprising that Randy, as a man of the left, says that black-white disparities in test scores really do indicate meaningful differences. And perhaps it’s surprising that, as a conservative, I say that a stronger social safety net—if properly calibrated—could help to ameliorate some of the problems of ailing black communities.

I don’t think that means that Randy is actually a conservative and that I am actually a liberal. Rather I think it’s an indication of how far off the rails the most dogmatic progressives have gone when it comes to race. The real, meaningful differences between the two of us seem small by comparison. Will they still seem so in the wake of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision? Despite knowing Randy’s thought and personality quite well, I’m honestly not sure. We’ll find out this week, and I hope to be able to post video of the debate soon so you can see for yourselves.

This post is free and available to the public. To get early access to episodes of The Glenn Show, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, comments, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

[This transcript has been edited and truncated in the interest of space. - Ed.]

GLENN LOURY: Welcome, everybody. This is Glenn, as you know, Glenn Loury, and I am very happy to welcome Randall Kennedy, an old friend of mine whom I’ve known since the 1980s when we were both, well, we were younger faculty members at Harvard at that time.

He’s a distinguished law professor. He’s written a lot of interesting books. Race, Crime, and the Law is this encyclopedic treatment of race, crime, and the law that, gosh, it must be 20 years old by now Randall or something like that, but it’s a monumental—Interracial Intimacies, another one of these big books that I would never even think of trying to write, where he gives a comprehensive treatment of American legal systems dealing with race in terms of marriage adoption and interpersonal relations. Randy has written a book about the N-word, a history of the N-word, in which he uses the N-word in the title of the book. That’s audacious. That’s courageous. He’s a distinguished professor of law at Harvard.

We are here to discuss the topic du jour, which is systemic racism, Black Lives Matter, and police violence. Which is affirmative action. Which is what’s the argument for and against reparations? And we’re going to have that discussion, perhaps not in the register that you would be used to hearing in a seminar in the economics department where people are presenting data and models and making scientific arguments, but rather then a more—I don’t know—popular and political, hopefully not polemical, vein in which we talk about these issues as public intellectuals, which is one of the sidelines that both of us pursue. Randy’s a social democrat. He can speak for himself. He’s a man of the left. I’m not. I guess you know that. I’ve been out there. I have a podcast. Everybody can hear what I’m saying about all these issues of the day. I’m notorious. I’m not going to apologize for that, but I thought that it might be helpful to the engagement the department is having with this issue to temper or leaven our conversation with some of these public, intellectual, political, and legal considerations that will come up in this discussion.

I put an essay in the City Journal, that’s the organ of the Manhattan Institute. The piece is “Why Does Racial Inequality Persist?” And there, I put forward a theory. There’s nothing new in that theory that I put forward relative to the stuff that I said going all the way back to the 1970s, which is basically, there’s a supply side to the labor market. There’s discrimination. There’s the discrimination coefficient—Gary Becker, The Economics of Discrimination. We sent testers out to buy something or to apply for employment, and we get a clean estimate of the difference in the likelihood that a job is offered based upon the race of the person who’s being interviewed or whatnot, and we got a measure of discrimination. There’s the behavior of the employers on the demand side of the labor market. There’s also a supply side to the labor market. There are the skills, both soft and hard skills, cognitive skills and behavioral skills that people bring to the labor market. That’s the supply side of the labor market. Those skills come from somewhere. They come through processes of development, human development, which are contextualized. They depend on family. They depend on community, on peer groups, on culture. They also depend on institutions, on schools, and on the larger social provision, but the supply side of the labor market matters.

So I’ve been arguing that the contemporary discourse is distorted. The invocation of systemic racism, structural racism in the face of every disparity undervalues the significance of the supply side of the labor market. I’m not only talking about the labor market. I’m also talking about the supply side of the criminal offending market. Mass incarceration is systemic racism.

Well, what about the disparity in the offending behavior between racial populations? Where did that come from? “Oh, that too is a result of systemic racism.” Now we’re explaining the supply side, in this case, of the criminal offending market in terms of the structure.

Really? That’s all that’s going on? There are no cultural issues? There are no values issues? There are no behavioral issues? Behavior is itself a consequence of the structure, so there’s no human agency? There’s no autonomy? There’s no free will? It’s predetermined by the fact of the historical mistreatment of people by race that their behavior on the supply side of the labor market or the criminal offending market—I just give those as examples—would be disparate. That’s a known weight on them. That’s a weight on the system.

I’ve been arguing against that. I call it the distinction between the bias narrative and the development narrative, which just says I see a disparity and there well may be bias. I don’t preclude that as a possibility, but there are other things as well. There are development things. There is the structure of the households, of the families from which the young people whom we’re talking about are common. What was going on in the community, the neighborhood where they grew up? What were the promptings of the peers with whom they affiliated? What got valued? What were their ideals? What were the norms? What were the entitled institutions within the communities from which they came that either did or did not foster their personal development? I want to take that seriously.

I’m exercised by the fact that, for example, in American public schools, black kids—especially boys—are suspended for disruptive behavior at a significantly higher rate. I don’t have the statistics in front of me, but they would be easy to find. Vastly greater rates of suspension from school for disruptive behavior for blacks than whites, and for black men particularly. In the second of President Obama’s two terms in office, the Department of Education undertook to address this problem by sending a warning letter around to the many thousands of public school districts in the United States pointing out to them that if they were continuing to present racially disparate suspension rates, they would fall prey to civil rights investigations that actually might compromise their eligibility for federal funds because they would be in violation of civil rights laws.

In other words, they presumed that the fact—disparate suspension rates by race—was a reflection of bias, of school districts treating kids differently by race. I point out, however, that in fact, a plausible hypothesis to be investigated to the empirical question is that there are significant racial differences in the frequency of disruptive behavior being exhibited by kids for reasons we can go into. I won’t claim to understand them all, but that could be and probably is deeply implicated in the factual predicate here, which is that there are racial differences in rates of suspension.

And I say as a hypothetical, suppose that’s true. It’s not implausible to say that, because we know there are very large racial differences in criminal offending rates in young adult populations only a few years older than high school kids who might be being suspended for disruptive behavior in public schools. It’s not implausible to think that there are supply-side differences in the behavior between racial groups, reasons for which could be deduced. But suppose it’s the case that the problem here is not so much one of school districts treating black kids differently as it is of black kids behaving differently.

Diagnosing that problem as one of bias and prescribing civil rights enforcement in response to it is exactly the wrong thing to do if, indeed, my hypothesis of differences on the supply side is correct. Rather, an inquiry into the underlying structures that are responsible—whether it be what’s going on in the homes of these kids or maybe it’s about the nature of social policy in areas other than education that gets acknowledged—first of all acknowledges the reality of the difference by race in the disruptive behavior and then addresses itself to that rather than the hypothesized bias of the school district. That would be the way to respond.

I think there’s a lot of stuff like that. We have too many people in prison in the United States. I actually think that that’s true. I’ve written a book about it. Too many young people in prison in the United States, and there’s a huge racial disparity in the people who are in prison in the United States. That’s supposed to be “mass incarceration,” and that’s supposed to be a manifestation of systemic racism. I find that to be just a shockingly thin intellectual foundation for making social policy. The presumption that the fact of higher offending rates—and there is no doubt about that—amongst African Americans is itself a reflection of structural racism is rhetoric in my view.

I’m prepared to acknowledge that the so-called culture, that the patterns of behavior, that the structure of home life, that the nature of peer groups, that the segregation of neighborhoods and the organization of space in American cities, that the networks of social connectivity in between gangs that might be implicated in high rates of violence, I’m prepared to acknowledge that those things well might be in part the consequence of historical forces of American racism going back to slavery. But I don’t find that observation to be very helpful in telling one what to do. And I think that the politically correct reflex to look away from the reality of this difference on the supply side, the politically correct reflex to assign to racism, white supremacy, the responsibility for the causal basis for these differences of behavior, I think that’s very problematic. So I’m against that argument and I’ve been against that.

Let me say a few things about affirmative action. We’re fifty years into this regime. Affirmative action goes back to the late 1960s, early 1970s. The Supreme Court has spoken. We have a very distinguished lawyer here. I won’t attempt to pronounce on the legal aspects of it. Affirmative action in 1980, that’s one thing. We don’t have any blacks at the elite schools—or very, very few—because of a history of exclusion and because of the underdevelopment of the African population that left a relatively low number of young people who had the qualities that these institutions were looking for when they were admitting. Not their fault that they didn’t have better schools, that their parents didn’t have better incomes, that their neighborhoods were segregated.

So we institute practices aimed at bringing people on board who had been previously not included. We use a different criterion of selection. That’s fine as a transitional matter. It’s inconsistent with genuine racial equality as a permanent matter. You can’t have genuine equality of standing, honor, respect, dignity, and a sense of belonging in an institution in the steady state of a dynamical model if you’re using different criteria to select people into some elite, right-tail selection venue, because there’s going to be, on average, differences in the performance of the people selected into that venue if you’re using different criteria to select them.

What are the criteria? Let me make the model simple. The criterion is a test score. Of course, the criteria are multidimensional, but let me just say it’s one thing, it’s a test score. The test score is correlated with post admissions performance. Again, performance is a multidimensional thing, but let me just say it’s one thing. It’s your GPA when you get in. There’s a criterion that you use to forecast, in effect, what people’s performance is going to be after admission, and the model that I have in mind is that the school has a limited capacity and more applicants than seats. It selects the people who it thinks are going to perform best by using the pre-admissions criterion to predict their performance and, therefore, establishing a cut-off line above which those are admitted and below which not. Again, the model is simple. One-dimension assessment of potential, one dimension of performance. I understand the real world is more complicated than that.

I’ve got two populations, black and white—let me say again, keeping it very simple—and for historical reasons, there are differences in the endowment of abilities and opportunities to develop these abilities that leaves these populations at the time of application with a different distribution of indicators of performance, lower test scores on average, but I’m determined to have a proportionate representation of the disadvantaged population, so I have to set a lower threshold for submitting them.

The fact of the matter is, so long as the pre-admissions indicia of assessment—in this case, the test score—are correlated with the post-admissions performance and I’ve got a large sample, if I use different cutoffs, I’m going to have incumbents who get selected who have post-admissions differences in the distribution of their test score, because I’ve used a different cutoff. But if the test score is correlated with performance, then on average I’m going to have differences in post-admissions performance as a statistical necessity given that the pre-admissions criteria were correlated. And by the way, if they’re not correlated and the use of them would cause you to have lower representation of the disadvantaged group of African Americans, why are you using them? We shouldn’t be using them at all if they’re not correlated. They are correlated. We are using them, and therefore, we have to anticipate differences in post-admissions performance.

That, to my mind, is a tolerable circumstance in transition but, according to my conjectured theorem, inconsistent with a steady state in which there’s genuine equality. Because there’s not going to be equality of achievement if there’s differences in the criteria of assessment that are used to admit people. That, as a permanent matter, as a permanent way of doing business, I’m claiming, is inconsistent with “true equality.” And moreover, it invites a lot of unhealthy stuff. It invites dis-attention to the objective differences in performance. It invites condescension. It invites shame on the part of the people who are, as it were, assigned in a manner that leaves them setup for … I’m not going to call it failure, because nobody fails at the top-end schools. Nobody literally fails.

But as Peter Arcidiacono has been showing in some of the studies he’s done at Duke about kids who switch out of STEM—discipline major election—when they come in at Duke, they are electing STEM classes, but some proportion of them switch out and go into the softer fields of study, less quantitative fields of study. He finds that if you control for entry test scores of the black kids and the white kids at Duke, they leave early-election STEM majors and switch over to sociology at roughly the same rate, but because the test score differences are so large between the black kids who are going into STEM as freshmen at Duke and the white kids who are doing so, the black kids’ actual attrition rate from the STEM disciplines is, like, twice as high or three times as high as the rate associated with white kids. There are differences in their performance, in this case, in the STEM disciplines post-admission that are accounted for by the differences in the test scores that they presented prior to having been admitted.

So I am trying to sound an alarm, and I’m going to sound like a curmudgeon or a conservative. I’m not against affirmative action as such, but I’m very concerned about the permanent institutionalization of this mechanism which avoids the development problem. It avoids actually addressing the underlying problem of the failure of the African American kids, statistically speaking, as a population to realize their full human potential. I’m quite aware to stipulate that there is no difference in the underlying potential of the human populations in question by race, but the processes of development can’t be short circuited. They actually are real things. Acquiring mastery over the secondary-school curriculum as a prerequisite to being able to take most advantage of elite higher education is a real thing. The test score differences are telling us that there are differences in the extent to which these populations have acquired that mastery. By using an instrument of selection that favors the disadvantaged population, you circumvent the very hard and historically necessary task to addressing yourself to the failure of those populations and the institutions that serve them to acquire the mastery over this material.

I don’t see equality in its rightly understood sense in the steady state of a dynamic system of this sort being achievable by that method. There’s no substitute for actually addressing the disparate-by-race development of the human populations that we are dealing with when we are making selection decisions.

That’s one argument. That’s an argument about affirmative action. I’m going to say a few things about reparations, and then I’ll stop, and thank you for allowing me to just have opinions, because these are all opinions. These are not scientific claims. They’re not uneducated opinions, but I grant you that they’re opinions, and certainly people will and should push back.

What I want to say about reparations is that I think it’s a very bad idea for America and it’s a very bad idea for black people. Let me say why I think that. When the victims of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese American citizens in camps at the beginning of the second World War—citizens rounded up, dispossessed, herded into camps because they couldn’t be trusted—that was awful, and in the fullness of time, the American government came to recognize it. Reparations were paid to the victims of this horrible policy of the American government. Those were actual American citizens who had been interred in camps. They were old. Some of them had died before they could be recognized. There were 80,000 of them, and each of them got $20,000. It was a one-time payment. $1.6 billion.

People are talking about 40 acres and a mule, and they’re using an interest rate machine to bring that forward to some numbers of tens of thousands of dollars per head of African Americans and they’re talking about a population of 35 or 40 million people. We’re in the trillions. The United States government, I claim, ought not to create a social program on the scale of social security. Trillions of dollars calibrated by, rooted in, and defined by the race of its citizens. That’s South Africa-esque. It’s a profound mistake for the country. We ought to deal with the problems of people who have problems in our society, whether it be housing, food, insecurity, they need job training, better education, income supports, whatever. To carve out a special fiscal dispensation on the scale of trillions of dollars based upon the race of American citizens is a mistake, I maintain.

That’s my moral argument. I could flesh it out. I have fleshed it out in other things. My more political argument is the consequences of, what do advocates of reparations cite? They cite slavery. The labor of the slaves was seized without compensation. That’s not entirely true, I have to say, because after all, the slave population had to be housed, fed, and clothed, and so forth. I know, I know, I know. Fogel and Engerman. Don’t blame me. Don’t blame me. Fogel and Engerman. It’s not true that there was no compensation, but it is true that they weren’t paid wages. I don’t know what it was like to be a wage laborer in the Irish ghettoes of Boston or New York in 1880 or 1870. I expect that the employers were exploiting their labor as well.

I expect a claim could be made that that exploitation of labor—especially if you were inclined toward a more Marxian view about these things—represented an expropriation—that’s the word that Marx uses, in fact—of the surplus created by that labor, and you could go down that route as well. So I think the accounting problem of determining exactly what was extracted over and above fair value as a consequence of slavery—a horrific institution, I’m not confused about that. Chattel slavery, forced labor: horrific. But one basis of the claim would be that. Another basis of the claim would be Jim Crow segregation, red-lining, American law and government biased against African Americans in the ways that materially deprive them of remuneration to which they ought to otherwise have been entitled, and so on.

And then you get a number. The problems of broken families, of high crime rates, of gangs, of violence. Homicide off the charts. The problems of academic underdevelopment. Look at the National Assessment of Educational Progress test score data for 4th, 8th, and 12th grade American students. The disparities in these nationally represented samples in terms of cognitive development, reading, and mathematics are monumental. They’re huge. Look at the offending, the crime rates. Look at their population. These things are racially disparate, and these disparities will not go away with a transfer of wealth.

In fact, if we have a dynamic model in which we thought about the steady state distribution of wealth holdings, the fact that I change the initial condition of our wealth, if I’ve got an ergodic property to dynamic transition process, it’s probably not even going to have any effect after a couple generations. We’re going to revert to whatever the steady state would have been.

So if we’re not addressing the underlying developmental factors that accused there to be a disparity in the first place, transfer is not going to solve that problem. I think the problem should be viewed as an open-ended commitment of the government to address the needs of its people, especially its most disadvantaged people, among whom African Americans will be overrepresented because of history. I think that succeeding in a reparations advocacy in effect commodifies and cashes out that open-ended claim. I think the superior political program is for African Americans who do have moral capital in virtue of our history of mistreatment— slavery and exclusion—to take that capital and put it with the broader claims of working people for a more effective welfare safety net for all of us, for all Americans.

Yes, there was racial injury. But the appropriate remedy for that injury, in my view, is not a racially defined compensatory program, both for the reasons that I have stated. We don’t want to get into that business, 30 or 40 million strong in the twenty-first century here, but also for the reasons that the effect of doing so will have been to discharge what otherwise ought to have been an open-ended obligation of the country to address itself for as long as it takes to the human suffering that the history of racial mistreatment has engendered. Which human suffering is paralleled by the suffering of tens of millions of Americans who happen not to be the descendants of slaves.

Okay, so that’s my speech. I’ll turn it over to Randy.

RANDALL KENNEDY: Well, first of all, thank you very much. Thank you for inviting me to share the forum with you and, like I said, I look forward to a good discussion. The first thing I say has to do with not so much the arguments that were set forth, but in a way the direction of argument. In a minute, I’ll talk about some of the particulars that Glenn just mentioned, and frankly, there’s a lot of what he said with which I agree. An awful lot with which I agree. And in fact, as I was listening to him, I was thinking, “Well, what’s the big difference? What’s catching with me? What’s bothering me?” And I’m going to start off with the thing that I think most bothers me about the presentation that you just gave, Glenn, and what bothers me about much of your writing, and I think what bothers me about much of my writing. I’m talking about you, but much of what I’m about to say I want to say out loud and I’m saying partly to myself, because I think in certain ways you and I share a sensibility, and I think that the sensibility we share is one that has a big problem.

Here’s the big problem. The subjects that really get you going the most—the most energy, the most fervor, the most emotion—is when you are criticizing the people who march under the banner of, let’s say, critical race theory, the people who march under the banner of Ta-Nehisi Coates. Systemic racism, abolition, the people who have these various tropes. I disagree with many of them, just like you do, and I tend, too, to get most upset with them.

But I think there’s a problem there. Why are we getting most upset with them in a world in which Donald Trump is the sitting president of the United States, in a world in which the Republican party for the past four years—and frankly, before that—has been a thoroughly obstructionist party, clearly not attuned to doing anything to address the massive social problems that confront the United States and that have an all-too-familiar racial pattern to them? A pattern with respect to indicia of wellbeing. The darker you are in the United States, as a general matter, the worse-off you are. I don’t care if we’re talking about length of life, access to healthcare, susceptibility to criminality, risk of incarceration, you name it. And I would say with respect to you, and I would say this with respect to myself, more energy, more attention ought to be paid to the powers that be. I’m not saying don’t be critical of these other folks, but the powers that be should be the places that get more of our critical attention.

And I would say there are two questions—and you mentioned one, but you didn’t really follow through. You talked about, “What is racial equality?” I think that’s great. That’s a great question. It’s a question that is subsumed [by another]: “What do we want?”

If I put that question to myself, you know, “Randy, you’re the king for a minute. You’ve got the magic wand in terms of racial equality. You can do whatever you want. You don’t have to worry about any external forces. You don’t have to worry about democracy. You can do what you want. What would you do?” The fact of the matter is—and it’s an embarrassment—I wouldn’t handle that question as satisfactorily as I’d like. And the reason why is because I haven’t thought about that question nearly enough.

What is it that we want? What is racial equality? What would racial equality look like? As soon as we ask that question, then we start talking about affirmative action. I’m happy to talk about affirmative action. It exists. We can talk about it. We can talk about reparations. But those debates I think are often digressions. We should focus more on, what would racial justice entail? What would it mean? What would reaching the racial promised land, what would the topography look like? What are its boundaries? How would we feel? How should we feel? What would it look like? I think that we should focus a lot more on that, and what needs to be done. After we think about what we’d like, how, as a practical matter, do we get there? I think, Glenn, that you and I spend too much energy, too much time, too much effort on issues that are real, they’re there, but they’re not the ones that should call upon our main energy.

Now, having said that, let me turn to some of the things you said. You know, your development hypothesis and your bias hypothesis. I agree, to tell you the truth, with that. The one thing I’d say, there’s no need to put them either/or. I think that they’re both true and they both act on one another. The history of racial oppression in the United States has created communities—all too many communities—that fosters the mindset, the conduct, the incentive structure that you criticize so sharply.

The question, for instance, of criminality. Yeah. You’re absolutely correct, and I get really upset. There are some places you go, certainly in my precincts and law schools, if you say there is more violent criminality in certain sorts of neighborhoods than in other neighborhoods, people really want to fight you. “What?” Yes. You go to certain parts of Chicago, you go to Compton. Yeah, the situation on the streets of Compton is different than the situation on the streets of Beverly Hills, all right?

I get really impatient with this desire to pretend that’s not true. Of course it’s true. Take a look at black people’s susceptibility to homicide, to rape, to armed robbery, to various forms of violent criminality, and where does that come from? I don’t think it’s innate. I think it’s situational. You live in a certain situation. You are deprived of certain things. You’re around certain influences, and it’s going to show itself. I don’t think that the development story is a conservative story, a right-wing story. I believe in that story.

I consider myself a person of the left. My peeps are the people who turn out the American Prospect, the Nation, Dissent magazine. That’s where I hang out. And I don’t think that the development story is outside of that. If it was the case that folks were being held down, if that was the only problem, then, well, if you could just get the hand off, they’d pop up and everything would be all right. No, no. It’s actually more tragic than that. The wages of racial oppression in the United States have had a debilitating influence on people. People want to act like the wages of oppression do not have a debilitating influence on people. Yes, they do. They actually do. It actually changes people. It actually makes people … you want to be away from them, and people don’t really want to face I think oftentimes the wages of racism.

You talked about affirmative action. I’ve been in many classes. I’ve taught affirmative action classes a million times, and there is a point when you’re talking where you’re walking for the affirmative action cases, in my experience, it gets really tough because I think in the classroom—especially with the black kids—there’s a feeling of shame. There’s a feeling of shame because you people are talking about the charts, who scored this, and blah, blah, blah, and there’s this feeling of shame. And people want to say, “No, there is no real difference. There really is no difference,” you know? This kid got 750, this kid got 550, but there really is no difference. That difference in 200 points is just because of the questions they asked or something. People come up with all sorts of things, and it’s very tough because, you know, I say there’s a difference. There is a difference. The kids with 750, there’s a reason why they scored 200 more points. They know more. They are, at this point, more capable.

And why? Are we surprised by that? We shouldn’t be surprised by that. Black people got out of slavery in 1865. That’s not all that long ago. And then their parents were deprived. What, you think that that’s going to go away fast? No. We are working with the wages of racial oppression, and it’s tough to swallow that because somebody is saying, “Does this mean you are lesser-than?” And I say, “Yeah. Yes. And you’ve got to accept that.”

But that shouldn’t be the end of the story. Just because you’re behind on day one doesn’t mean that you have to be behind on day 365. But do recognize you are behind on day one. And if you don’t recognize you’re behind on day one, you’re not going to take the steps to catch up.

So Glenn, I agree with much of what you say about the development thing. I think there is bias. I think that the bias, however, is complacency, not taking the steps necessary to grapple with the development issue, and the development issue I think is going to be very difficult to grapple with. But I don’t see the political will in our society saying we’re not going to take the South Side of Chicago, and the deaths, and the lack of education, and the blah, blah, blah. We’re not going to take that. We’re going to do something about it. I would like for people to be up in arms and wanting to do something about it.

Now, what is to be done about it? Frankly, I’m not altogether sure, but I do know that there ought to be a feeling. We are a rich enough country to make an inroad on the various hierarchies of inequality that we see, and I don’t see that, and I’d like something to be done about it.

On the question of reparations, I’ve been a proponent of affirmative action, and I still am a proponent of affirmative action. I’ve basically said that the best argument for affirmative action is it’s basically a reparations-based argument. To tell you the truth, for me, I want resources. I want our society to address need, and frankly, whatever argument will allow for that, okay.

In actuality, I’ve become less attached to the reparations argument insofar as, ultimately, it’s concerned with the history of one’s need. You’ve got to check this box. You know, something happened bad to my people. Well, I mean, if you’re a true reparationist, a true reparation-ist says give money to Oprah. If Oprah’s people were enslaved, give money to Oprah. Well, as far as I’m concerned, Oprah doesn’t need money. I want to give resources to people in need. There are plenty of black people in need? Fine. There are plenty of white people in need. There are plenty of Latino people in need. There are plenty of Mung in Cambodia, and I don’t care? I care. I’m interested in history, but I don’t think that the normative engine should run on a matter of history. I think the normative engine should run on some notion of human needs today. Let’s address those and move forward. There’s more to say, but let’s talk.

Well, let me come back to you a little bit. You ask me why I don’t spend my time attacking Donald Trump instead of attacking black people. That’s what I think I heard you say.

The powers that be.

And what I want to say to you is I get to spend my time how I want to spend it. Why is [that] a measure of the quality of my argument? I mean, think about the logic of that criticism. My arguments are not to be taken seriously because it’s not the argument that you would have me make.

No, no.

Yes, that’s what you said. Don’t attack Ta-Nehisi Coates and the Black Lives Matter people when I could be attacking the capitalists or something.

No, I think that’s a mischaracterization, so let me try again.

Okay, I beg your pardon. Please clarify.

I’m not saying don’t criticize whoever you want. Among the array of things to criticize, what does one pick to criticize? There are a lot of people who criticize the powers that be, and they do it badly. I would like for you to do it, because, frankly, you are smarter and more informed and more careful than a lot of the people who try, and therefore I would like for you and me to focus our energies on what I see to be the major problems. There are a variety of problems. I think that the critical race theory people or the Ta-Nehisi Coates people, I think that they warrant criticism in various ways, but I think that on the sort of spectrum of things to criticize, I would put them lower down on the pecking order. That’s all.

Let me just offer this. I see there to be two levels of conversation. There’s a public debate about what the United States of America and its various institutions should do that we resolve through our politics and through our civic discourse. And then there’s a communal debate about what black people should do. This is a loose association. It’s not a coherent organization that has a governing structure, but it nevertheless has sway. It has sway over the way in which black people carry on our lives, what we teach to our children, how we conduct ourselves in our various levels of endeavor.

I’m trying to weigh in on that. I’m trying to change the character of that discourse. I’m trying to say to people, nobody is coming to save you. If you really think that national politics is a solution to the South Side of Chicago, you must be crazy. You think it’s a program? You think there’s a piece of legislation and appropriation that is going to change the vicious, despicable, violent behavior that is taking lives by the score even as we speak? These things need to be condemned, I want to say.

I want to exhort. I want to call to higher ground. I want to show that there are other ways of looking at the world. Ta-Nehisi Coates is in contempt, in my opinion. Well, that’s too strong. I take it back. But he’s wrong-headed and he’s leading my people— my people, okay? Maybe some of my colleagues can understand me using phrases like “my people.” I got a people. We’re fighting for our souls. That’s how I see it.

On that, Glenn, we are in agreement. You mentioned Race, Crime, and the Law. The central theme of that book was under-protection. The central theme of that book was, what about the neighbors of these people who are committing crimes? I’m all for due process. I’m all for giving everybody their rights. I don’t want anybody tortured. Fine. I also don’t want people committing crimes against their neighbors. And the neighbors need to be protected. That was a central thing.

On exhortation, I’m all with you. Here’s one thing I’d say though, Glenn. First of all, there’s some people in these audiences, they’re not going to listen to us, but that’s not our fault. They’re just not going to listen. I think that there are some people in these audiences, however, who might listen to us if they really think that we’re not just exhorting them, but that we are exhorting the country to be with them.

No, I don’t think that there’s some piece of legislation that’s going to set things right on the South Side. I do think there are things that are going to happen in Washington DC that can help set things right on the South Side. Again, both are necessary. There needs to be exhortation on the South Side, but we also need to go to Washington DC and talk about an economic policy for people who want to work. Is there something that we can do to enable people to work more and get a living wage? Are there things that can be done as a matter of social policy, governmental policy to help people? You don’t disagree with that, do you?

No, I don’t disagree with that. In fact, that’s how I’m leaning. I mean, I find myself more in the “progressive” camp some days than I would have ever imagined, because I find myself saying, “If we had a decent set of domestic policy structures … ” I’m talking about healthcare, I’m talking about housing, I’m talking about education in child development in early childhood and whatnot, I’m talking about incarceration. I mean, as I say, I spent a lot of time, years ago, reading, writing, and thinking about how we deal with crime and disorder in our society, and the extent to which the institutions that are charged with both punishment but also, as it were, rehabilitation are failing to function, and looking at how things are done in other places.

So we had a decent social provision. A lot of this racial disparity, I mean, it doesn’t have to be equal. It doesn’t have to be one to one. It’s the underrepresentation of people at the very bottom end that’s the most disturbing thing, and we can cushion the fallen people who slip below the water in society. That’s something we ought to do on behalf of the program of making ourselves into a more perfect union and a better place, period, for everybody.

you know , people in the struggle and those who critiqued need to accept the world has changed . we are not a black and white nation , we are truly diverse and in ways binary thinking no longer serves a purpose

As difficult as it may be, we must begin by scraping away the politics...scrape away the emotion .......to consider the fundamental question: what is racial equality?

The answer is quite simple. It's nothing.

Or rather it's nothing we here, in this world, can address beyond the elegance of the declaration : all men are created equal.

We agree, of course, but so what?

Does it mean we all look alike? We all weigh the same? Have the same hair color or nose size? Not in the least. Does it mean we're all equally smart, equally fast, equally quick, equally determined, equally competent at all equally available things? No, it doesn't mean that either. Does it guarantee in some Constitutional way that we'll all be equally successful, equally wealthy, equally positioned within an equal social & cultural context, equally shared? Of course not.

To say all men are created equal is to say only that all men are equal before God and -- or so we hope -- the Law. But the law is a very human thing, made by humans, administered by humans, and subject perpetually to human error. So the fact of our philosophical equality before it does not and cannot guarantee our perfect equality before the human understanding and administration of that law.

So what does it truly mean to say we are equal? It means that God considers us all the same.

But beyond that holy truth, we are as different as snowflakes. Born with unequal sets of genetic luggage, we walk into the unequal lives our unequal parents unequally made. Gifted with entirely different sets of talents, abilities, proclivities, strengths, weaknesses, tendencies, preferences, ambitions and fears...we each wrestle the very same question: what are we to do? How we answer that question produces, of course, nothing but more inequalities.

Truthfully, we wouldn't have it any other way. We strive, not to be the same as everyone else, but to be better, to achieve more, to make an 'unequal' life for our children which is better than the unequal life our parents made for us. And on it goes.

So given this understand, what then is Racial Equality?

Well, it's the same as any other kind of demographic 'equality'. It's an empty trope, a sounding brass. What could it possibly mean -- for Black people to be equal to Asian people to be equal to White People who are equal to Brown People (and every skin tone shade in between)? Quite obviously these things aren't true and can never be true in any kind of real world, tangible way: just line us up and look at us. Look at what we've done with our lives. Look at anything or everything and all you'll see is Difference.

Ah, but what about the Law of Large Numbers? Would we expect -- shouldn't we expect -- that equivalently unequal populations of individuals, taken as a massive group, demonstrate some kind of magical equal achievement averages, over time, in the long run? The best we can say is Maybe. Maybe, given a constant social & cultural equality of context across all populations, then maybe those large numbers over time balance out. But our social & cultural contexts aren't equal. Growing-up in a small town is vastly different from growing up in the inner city. Growing up with one parent is vastly different from growing-up with two. Having a drug addict for a brother is different from a brother who’s a valedictorian. To Glenn's very point, the 'developmentals' are not the same, and until or unless the State acts to standardize everyone’s ‘developmentals’.... to remove every child from that child's home and give him or her to the State to be raised within the loving embrace of the State, within a State home, taught by State Teachers, in a State approved fashion...those developmentals will never be the same.

And the ‘long run – over time’ question? Heck, I’d give it 2000 years – just a small moment carved from eternity. Come back to me when we have that data which measures the nature of social & cultural cross-group equality as we compare the year 1000 with the year 3000. Or what the heck, what about the comparison of the year 1000 with 2000? Just one measly millennium. That’s not asking too much is it? Well we can’t do that either. We think the ‘long run’ is two generations, maybe three. And of course it’s not, not if we want the ‘law of large numbers’ to be impactful.

As for Affirmative Action & Reparations, neither works. . Nor can we reasonably believe they should work. The NBA has existed for 77 years. 71% of the NBA is Black. 66% of the population is White. This is, no doubt about it, a massive racial inequality. Three generations of players have come & gone and STILL we have this massive outcome imbalance. Doesn’t AAction tell us we should be acting to fix that? Shouldn’t we be altering entrance standards (like playing outstanding college ball) to allow the ’lesser qualified’ (those who didn’t make their college teams) a place on the professional bench?

God no. No one wants that. No one is even asking for that because we all understand, intuitively, that two wrongs do not make a right. Mandating a ‘racially equal’ basketball team mandates Mediocrity AND it cheats those more qualified out of their NBA opportunity. The End, no matter how glorious it might sound, does not and cannot justify the Means. Because someone at some point in the past – who looked vaguely like me -- discriminated against someone else who looked vaguely like you...the fact of that wrongful discrimination does not mean that I owe you anything. It does not even mean that you are in any way owed. Two differently colored newborns in the nursery lying side-by-side do not enter the world with either an account payable or an account due.

So what remains?

The same thing that always remains:

“It matters not how strait the gate..... How charged with punishments the scroll... I am the master of my fate... I am the captain of my soul.

Unequal at birth, unequal in life we can only do what we have ever done which is, always and forever, ‘the best we can’. Where that best effort ends-up, how our life is then summed:

“We believe... in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther….And one fine morning — So we beat on, boats against the current...”

What else is there?