My "Perplexing" Response to Ta-Nehisi Coates's New Book

with John McWhorter

John McWhorter says he’s “perplexed” by my praise of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s new book, The Message. That’s understandable. Coates is, after all, one of “the people with three names,” that loose group of “antiracist” writers and intellectuals John and I have criticized over the years. We’ve taken them to task for their superficial and occasionally opportunistic analyses of race in America, their failure to reckon with the real problems within black communities, and their calls for institutions to balance the scales of racial inequity by lowering standards for African Americans. And, despite the seriousness of the issues, we’ve had more than a little fun doing it.

I stand by every word of my criticisms insofar as they’re accurately applied. But were any of these figures—even Ibram X. Kendi—to write or say something I thought praiseworthy or valuable or thought-provoking, I wouldn’t hesitate to say so. My problems with the people with three names have nothing to do with who they are—I don’t even know many of them personally. It’s what they think, say, and do that cause me concern.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has written a book that I find praiseworthy, valuable, and thought-provoking. I don’t agree with everything he says, and I certainly haven’t changed my mind about his views on “white supremacy” and reparations. But I cannot sit here and pretend The Message didn’t affect me deeply simply because I’ve criticized its author in the past. Doing so would be a terrible betrayal of my own principles, besides being profoundly unfair to the author. I have a special responsibility, after all the charges I’ve leveled at Ta-Nehisi Coates, to come out and say so when I believe he’s produced a work of great value.

And what is the value of this work? Ta-Nehisi Coates saw what he regards as a great wrong. He infused his writing with the outrage and suffering he saw in that wrong. And I share some of that outrage and sympathize with that suffering. I’ve written about it here. I spoke about it on my show this week, as I have in the past. Others have pointed out that by publishing The Message Ta-Nehisi Coates is unlikely to incur significant career damage for what he has written. The irony is that because I have praised him for that piece of writing the same won't be true for me. It's worth asking why that should be so.

This is a clip from the episode that went out to paying subscribers on Monday. To get access to the full episode, as well as an ad-free podcast feed, Q&As, and other exclusive content and benefits, click below.

JOHN MCWHORTER: I haven't read it, and so maybe I'm missing something, but boy have I read a lot of reviews, including Coleman Hughes's in the Free Press, which was excellent. Are you sure that Coates actually gives a principled justification of what I'm assuming is his opinion that Israel shouldn't have happened? Or does he cherry pick a few episodes from here and there? Does he make a real case that a public intellectual at his level is responsible of making? Does he appear to have done his homework?

GLENN LOURY: I think he's going to be susceptible to that kind of criticism. He didn't go deep enough. He didn't read enough books. He doesn't know enough. Douglas Murray and him in a debate? Douglas Murray is going to throw the book at him. “You don't know what you're talking about.” I wouldn't criticize his essay from that point of view. In a way, he knows that he doesn't know all the way down.

But his feelings are more important because he's black?

No, it's not his feelings. It's not his feelings. This is his position. His position is it's an apartheid state.

But does he address why?

And he's against apartheid. No, his position is that's wrong. If you watch these interviews, you've heard him use this device. He says, “I'm against the death penalty. And I'm against it whether you're applying the death penalty to someone who stole a candy bar or you're applying it to someone who slaughtered ten babies and then ate them. I'm against the death penalty. And therefore, when I see apartheid, and what I see there is apartheid”—this is his position based on his experience, and he describes in vivid detail aspects of what he's calling apartheid—“I'm against that.”

I'm not impressed by this.

And there's nothing the Palestinians could have done or are doing that's going to make me not be against that.

I'm not impressed by this at all. I find this a simplistic analysis of a very complex situation. Calling it apartheid, there's a certain music to it. Everybody jumps when you say it, just like he institutionalized the term “white supremacy” in the same way. But what would he suggest they should have done differently, given the reason for this apartheid?

It's very complicated. I imagine that his idea would be what a lot of this all comes down to is he thinks Israel shouldn't have been established. But what is his justification for that? Why should there not have been what's called a partition? And there've been partitions all over the world. I imagine that his reason would be because they're white and the Palestinians are brown. But does he come out and say that? Or does he just assume that we think that?

Why don't we circle back to this? I think you ought to read the read the thing that we're talking about, and then we can talk about it. But I'm going to answer you directly. He is against the project of establishing a Jewish state. He does think that an ethnographic definition of statehood in a population that is heterogeneous is deeply problematic.

And that's the moral starting point for his critique. He employs—and I can hear Coleman critiquing this move that he makes—his experience. As a descendant of slaves in the context of the United States, as a dominated people who have to deal with the subjugation, the stigma, the dehumanization, the relegation to the backwaters and the margins and the corners of society, and as a writer, as a moral agent in our time who has that history in his “blood,” to say that I can't countenance silently what I am observing being perpetrated here? To me, you don't have to have an answer to be able to defend that position.

What should Israel do? Why is it my responsibility to have an answer to that question in order to be appalled at what Israel is doing?

No, not with his influence and given how much is written about this, how richly it's been discussed. He's not responsible for coming up with a game plan, but he's supposed to explain why he thinks that there should be no Israel, especially because, in the same book, he says that we should embrace a mythology that we come from Egypt.

He doesn't say there should be no Israel. He says there should be no apartheid.

Does he understand the history that's led to this apartheid?

As much as any well read and intelligent person—and he is both of those things— could be expected to understand it.

And then, in the book, he never mentions what happened on October 7th, theoretically because he wrote it after that happened. But he uses the passive voice, “people were killed,” etc. The implication is that anything Hamas does is justified because, as you're putting it or he would put it, they are enduring an apartheid, which is not justified, because whether or not Israel is trying to protect itself from being bombed out of existence through this apartheid, it's all moot because Israel shouldn't be there in the first place.

Does he actually lay out that argument? Or are we just to assume that there should be no Israel and that therefore he doesn't have to mention October 7th when a book drops a year after that happened? Genuine question.

Yeah, I'm not going to answer that question. I'm not here to defend Ta-Nehisi Coates. I think there's an interesting intellectual challenge to all of us, not just him, in our time about the deeply disconcerting moral dilemmas, the tragic moral dilemmas that are raised by this historical development. And he's giving one man's [view]—he is not a random person taken off the street, he is an influential figure, I agree—rooted in his identity but also in his responsibilities as a writer and as a citizen in reaction to that. And I think it's worth pausing for a minute about that, because a lot of Jewish Americans and a lot of Israelis basically agree with him about the moral challenge which this tragic historical evolution confronts us with.

I can only tell you this. I can tell you as a person who doesn't come in predisposed to like Ta-Nehisi Coates, who spent a lot of time reacting—I did read Between the World and Me. It's well-crafted, but it it rubbed me the wrong way in many respects. And I've said so. We've had our time here criticizing Ta Nehisi Coates. I do teach his essay, “The Case for Reparations,” which is his signature long-form magazine journalism piece that really solidified his reputation. And I have a lot of problems with a lot of what he has written and what he has done.

But I picked this book up and put it down in the same day. Picked it up at the beginning and put it down at the end in the same day. It's a short book. And I thought, this is a fucking brilliant writer. The craft. It wasn't saccharine. It was silky, subtle, engrossing, captivating, really. Turns of phrase that I wanted to underline because I didn't want to not remember how enchanting some of the prose of the book is. And I thought again, to have been a student of writing directed by this guy or that received this book, having been his student, and to see this love of words enshrined in this way …

We can argue about the moral motivations of it. And in another voice, I would be arguing about it. As I've said, this “we” that he easily invokes about Africanness is, I think, deeply problematic. But I thought, this is a serious person.

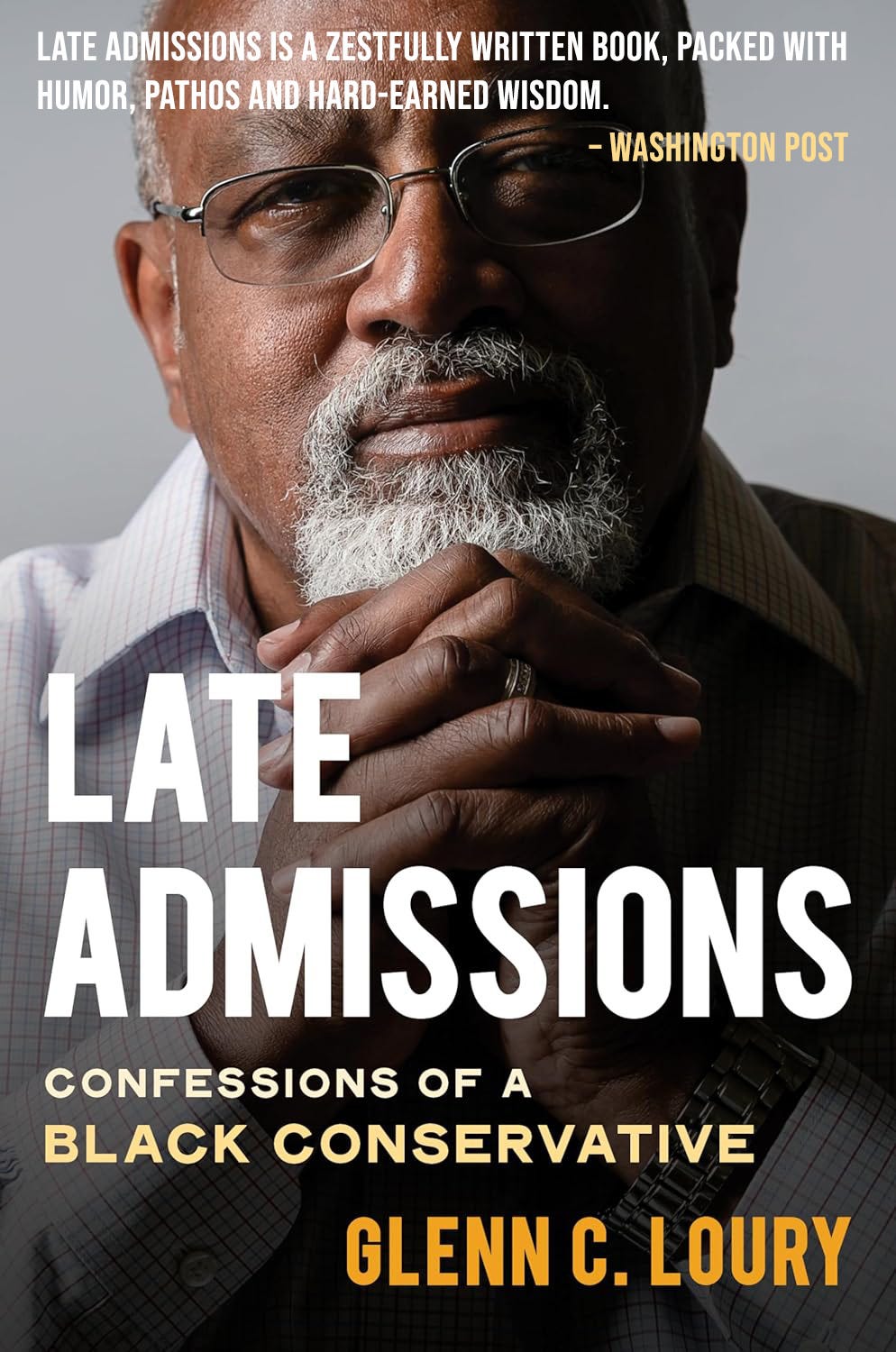

And I want to say something else. I felt a little bit like chastising myself for being so dismissive of this guy because I didn't like his politics. I didn't like his racial politics in 2015-16. I didn't like his racial politics in 2020. I was on the other side. I'm the conservative. Notes of a black conservative over here. But I thought I wasn't really open-minded and fair in assessing the quality of the mind and the artistry of this guy. I got to the end of that book, and when I put it down, notwithstanding his full throated criticism of Zionism, I said, that's a brave dude there. That's a dude who's speaking his mind and speaking the truth that he thinks he's been given to know, and he's taking his career in his hands when he does so. And more power to him. I don't have to agree with him.

Glenn, I am utterly mystified. With the risk acknowledged in that I have not read the book yet, I am utterly mystified. And I don't mean that rhetorically. I'm sitting here thinking that maybe I need to put my glasses on. I can't believe this is you saying this. And I'm trying to wrap my head around ...

Why not, John?

Because, yes, he has a way with words, and I'm not minimizing that. Yes, he's a very good writer, and I see that you're admiring that. But my issue with him, frankly, has often been whether or not—I hate to say this, but put it this way. I have never seen in him the frame of mind that tries to work out a problem, that looks at something that's complicated and tries to think out of the box to figure out a solution or to figure out an explanation, to go from A to B. It's always seemed to me that, for him, the constant leitmotif, the constant theme is “black good, white supremacy bad. I'm black.” That's everything. And so now he's applied that to Israel.

If you're going to look at something and call it apartheid and write artistically about it, that's one thing. But why the apartheid? When we call it a complex situation, I'm afraid that “complex” here means to simply diss Zionism right out. You have a case to make, especially if you're him. I'll put it that way. He's not somebody who seems to me to make a case and that's been true for his whole career. There's just a certain kind of feeling, and you and I used to agree that about that.

I know that maybe I'm missing something. For example, I'm not terribly literary. I probably read six fiction books a year. Usually three of them are ones that I've been told I have to read. I like to try to solve a problem. That's what linguistics is, although a lot of people have no reason to know that you're trying to come up with a solution to something. And that's what economics is. And so maybe I'm just the wrong person.

I'm going to read that book. But I'm really surprised that you are so willing to let pass the ratiocination that one would expect, given the richness of this topic. You're saying he's no Kendi, and I've always thought that he brings more to the table than Kendi, certainly. But to do this whole thing, “it's apartheid,” and to say nothing about the 1,200 people who Hamas killed and the 200 more who were taken into captivity and many of whom are dying now—that doesn't get one mention? That strikes me as almost willfully uncomplex.

You're saying that there's something about this book that transcends all of that, and I'm open. I will read it this week. I'm gonna write it down, make sure I do it.

Okay, why don't we circle back to this topic. I'm not gonna try to respond to your disappointment in me for not being as critical

I'm sorry, Glenn! I'm perplexed. Perplexed.

We will revisit the subject and leave it at that for now.

There is no dilemma Glenn. By and large, Palestinians do not believe in a two-state solution. They believe in a one-state final solution--with Jews annihilated or at best oppressed as a persecuted dhimmi class. In the last 24 years, Christians in the W. Bank are down from 19 to 2%--the same exact trend of ethnic cleansing that eliminated perhaps 20M Christians and ethnic and religious minorities in the Mideast over the last 100+ years starting with the Ottoman genocide against the Greeks, Assyrians, and Armenians. Every accusation by Israelophobes is a confession.

This is why there is no Palestinian sponsored peace plan on the table, never was, and no one--other than a Holocaust denier--with whom it could be performatively negotiated. And those who suggest leaving the W. Bank would solve all our problems, somehow got amnesia forgetting what happened with the experiment in Gaza: five unprovoked wars and tens of thousands of rockets culminating in the barbarism of Oct 7th.

So, "justice" in IslamoFascist IslamoLeftist terms means eliminating the only Jewish state (literally 1/1,000th of the territory of the Middle East) for the 50th Muslim Sharia state? After the Arabs already ethnically cleansed 850,000 Jews from 17 of 17 Arab states? (And people always forget this started as a Jewish/ Arab/ Islamic issue, not Israeli / Palestinian--and that more than 50% of Jews in Israel are beige and brown-skinned Mizrahi or Sephardi). And free Palestine looks a lot like "Free Iran." Government sponsored sexism, homophobia, oppression of Jews and/or ethnic and religious minorities. No free expression. Death for blasphemy. Death for apostasy. Honor killing. And perpetual ultraviolence. Until the Anschluss with the Hashemite occupied state of Jordan (aka Palestine #1) to reestablish the Islamic Caliphate.

Read the first few articles of the UN Charter (which the UN apparently hasn't. or amnesia is becoming epidemic) and tell me how, by any measure, they qualify for an independent state? They could in the future, but they're not going to get there with Islamic Supremacy, martyring their children, pay-for-slay programs, antisemitism, hatred of the non-Muslim, celebrating if not participating in rape, torture, mass murder, kidnapping, and/or burning families alive.

Either we believe in and protect the very base ideas of universalism and liberal society or we close the UN, pack up, and all go home scratching our balls as we lament Popper's iconic and oft ignored quote on the paradox of tolerance.

Not that it matters to Glenn - or anyone else, but a few things he’s said over the last few months gives me serious pause about my respect for someone I previously admired greatly. Something else is going on here, and I don’t know what it is. It’s almost comical, too ‘on the nose’ to say about Coates: “We’ve taken them to task for their superficial and occasionally opportunistic analyses of race in America, their failure to reckon with the real problems within black communities, and their calls for institutions to balance the scales of racial inequity by lowering standards for African Americans.” Without realizing that this is the central criticizm of The Message, the very book Glenn is pushing and praising! Similarly, Glenn has called Israel’s military response to Oct 7 “indiscriminate” - any serious empirical review demonstrates clearly the response has not been indiscriminate (exactly the opposite) and yet this man I admired - even revered - an economist whose life’s work is studying the empirical somehow gets this backwards? Honestly, much has confused me regarding world response since Oct 7, but nothing has given me more to think about than Glenn Loury’s blind spots in relation to Israel, Antisemitism and campus protests. I keep dreaming of a serious discussion with Coleman, Noam Dworman, Bari Weiss, Douglas Murray or Sam Harris, Ben Shapiro. And then he invites Norm Finkelstein? I am dismayed. Crushed.